Space is big. You know that. Everyone knows that. But when we talk about the distance of one light year, our brains usually just give up and file it under "really far away." It’s a bit of a trick, though. See, a light year isn't a measurement of time, even though it has the word "year" baked right into the name. It’s purely about how much ground—or rather, vacuum—you can cover if you’re moving at the ultimate speed limit of the universe.

Honestly, humans aren't built to understand these scales. We think a ten-hour flight to Tokyo is a long trek. We think the 238,000 miles to the Moon is a massive gap. But a light year? That’s 5.88 trillion miles. Or, if you prefer the metric side of things, about 9.46 trillion kilometers. If you tried to drive a car at highway speeds to cover one light year, it would take you about 10 million years. You’d need a lot of snacks.

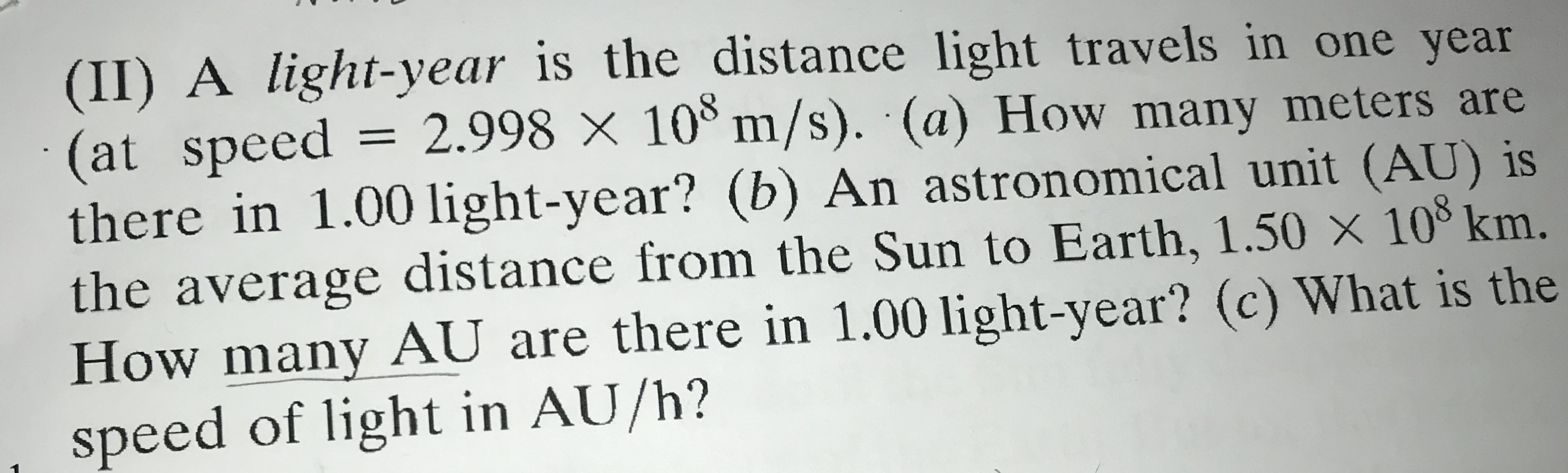

What is the Distance of One Light Year, Really?

Basically, light is the fastest thing there is. In a perfect vacuum, it zips along at roughly 186,282 miles per second ($299,792,458$ meters per second). To get the distance of one light year, you just take that speed and multiply it by the number of seconds in a Julian year (365.25 days).

Why do astronomers even use this? Because miles and kilometers become uselessly small once you leave our solar system. It’s like trying to measure the distance from New York to London in inches. The numbers get so long they stop meaning anything. Even our nearest neighbor star, Proxima Centauri, is about 4.2 light years away. If we used miles, we’d be talking about 25 trillion miles. It's just easier to say "4.2."

The Speed Limit of the Universe

Albert Einstein’s theory of special relativity tells us that nothing with mass can ever reach the speed of light. As you get closer to that speed, your mass effectively becomes infinite. You’d need infinite energy to keep accelerating. So, while we use the distance of one light year as a yardstick, it’s a yardstick made of something we can’t actually touch. It’s a theoretical maximum for travel.

Interestingly, when you look at a star that is ten light years away, you aren't seeing it as it is right now. You’re seeing it as it was ten years ago. You are literally looking into the past. If that star exploded this morning, you wouldn't know about it for a decade. The light is still "in flight," crossing that massive 58-trillion-mile gap.

Breaking Down the Math (Without the Boredom)

Most people get tripped up on the "year" part. Think of it like this: a "walking-hour" would be how far you could walk in sixty minutes. For most people, that’s maybe three miles. A light year is just that, but for a photon.

- Light travels ~300,000 km every single second.

- There are 60 seconds in a minute.

- 60 minutes in an hour.

- 24 hours in a day.

- 365.25 days in a year.

When you crunch those numbers, you get that staggering 9.46 trillion kilometers. NASA’s Voyager 1, the farthest human-made object, is currently screaming away from us at about 38,000 miles per hour. Even at that blistering speed, it hasn't even covered one percent of a light year yet. It’s been out there since 1977. That should give you some perspective on how lonely the neighborhood really is.

Beyond the Light Year: Parsecs and AUs

While the distance of one light year is the famous one, professional astronomers often prefer the "parsec." It stands for "parallax second." One parsec is roughly 3.26 light years. It’s based on trigonometry and how stars seem to shift against the background as Earth orbits the Sun. It sounds nerdier, and it is.

🔗 Read more: Why the Lewis Dot Diagram for Iron Is Actually a Trick Question

Then you have the AU, or Astronomical Unit. This is the average distance from the Earth to the Sun, about 93 million miles. Light takes about eight minutes to travel one AU. So, the Sun is "eight light-minutes" away. If the Sun vanished right now, we’d still have eight minutes of sunshine and gravity before we realized everything had gone south.

[Image showing the difference between an AU, a light year, and a parsec]

Why We Misunderstand These Distances

Sci-fi movies are mostly to blame. When Han Solo talks about the Millennium Falcon making the Kessel Run in 12 parsecs, he’s using a unit of distance, not time (which actually makes sense in the context of the movie’s lore, but it confused people for decades). In movies, ships jump to "warp" or "hyperspace" and cross light years in seconds.

In reality, the void is punishingly empty. The distance of one light year is mostly just... nothing. A few atoms of hydrogen here and there. Maybe some stray dust. But mostly just cold, dark vacuum. This emptiness is why it’s so hard to find exoplanets. We’re trying to see a tiny, dim marble sitting next to a massive searchlight (a star) from trillions of miles away.

💡 You might also like: Número de teléfono virtual gratis: Por qué casi todos son una pérdida de tiempo y qué opciones sí funcionan

Real-World Examples of Light-Year Scales

- The Moon: 1.3 light-seconds away.

- Pluto: About 5.5 light-hours away at its average distance.

- The Milky Way: About 100,000 light years across.

- Andromeda Galaxy: 2.5 million light years away.

Think about that last one. When you see a photo of the Andromeda galaxy, you are looking at light that started its journey before Homo sapiens even existed. That light has been traveling through the void for 2.5 million years just to hit your retina or a telescope's sensor.

The Practical Difficulty of Crossing a Light Year

We are nowhere near being able to cross the distance of one light year in a human lifetime. Current chemical rockets—the kind we use to get to the ISS or the Moon—are too slow. To get to the nearest star in a few decades, we’d need something radical.

Breakthrough Starshot is one real-world project trying to solve this. The idea is to use high-powered lasers to push tiny "nanocrafts" with light sails. They hope to reach about 20% of the speed of light. At that speed, they could reach Proxima Centauri in about 20 years. But even then, we aren't sending people. We're sending sensors the size of a postage stamp.

There are also theories about ion drives or nuclear thermal rockets. They are much better than what we have now, but they still don't make the distance of one light year feel "short." Space is just fundamentally hostile to the idea of quick travel.

🔗 Read more: Why Your 3.5mm to USB C Adapter Still Sounds Bad (and How to Fix It)

How to Visualize a Light Year at Home

If you want to wrap your head around this, try a scale model. If the Earth was the size of a grain of salt (about 0.5mm), the Sun would be the size of a golf ball about five meters away. At this same scale, the distance of one light year would be about 310 miles (500 kilometers).

Imagine that. A grain of salt in New York and the "light year" line is all the way in Richmond, Virginia. And remember, the nearest star is over four of those light years away. The scale is just haunting.

Is the Light Year "Fixed"?

Sorta. Because the speed of light in a vacuum is a universal constant ($c$), the distance is fixed. However, space itself is expanding. This is the weird part of cosmology. Galaxies that are very far away are moving away from us faster than light can reach us because the space between us is stretching. This means there’s a limit to how far we can ever see, known as the "observable universe."

Actionable Steps for Amateur Astronomers

If you’re fascinated by these scales, don't just read about them. Go see them. You can't see "a light year," but you can see the objects that define these distances.

- Download a Stellarium app: Use it to find Proxima Centauri or the Andromeda Galaxy. Looking at them while knowing how far that light traveled changes the experience.

- Calculate your "Light Age": Take your age in years. That’s how many light years away a star would have to be for its light to have started its journey when you were born. If you're 30, look for stars roughly 30 light years away (like Vega, which is about 25). That light is almost as old as you are.

- Follow the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) updates: This telescope is looking at light from over 13 billion light years away. It's effectively a time machine looking at the birth of the first galaxies.

- Support Light Sail Research: Look into the Planetary Society. They’ve successfully deployed light sails in Earth orbit, proving we can use the "pressure" of light to move, even if we aren't at light speed yet.

Understanding the distance of one light year isn't just about big numbers. It's about realizing our place in a very large, very old, and very quiet universe. It’s humbling. It makes our little blue dot seem a lot more precious when you realize the nearest "next door" is a multi-trillion-mile trek through the dark.