Most people think they know the on top of old smokey lyrics because they sang some goofy version about a sneezing meatball in elementary school. It’s a campfire staple. A nursery rhyme, basically. But if you actually sit down and look at the "real" verses—the ones collected by ethnomusicologists in the Appalachian mountains over a century ago—it’s actually a pretty brutal song about heartbreak, betrayal, and the realization that most men are basically liars. It isn't a song for children. It's a warning.

The song is a "mountain ballad." That sounds fancy, but it just means it was passed down by folks who didn't have Spotify and had to remember tunes by heart. Because of that, the lyrics have drifted. They’ve warped. One person’s "Old Smokey" is another person’s "clinch mountain." But the core stays the same: a lonely soul standing on a mountain top, looking down at a world that just broke their heart.

Where the on top of old smokey lyrics actually came from

We honestly don't have a "birth certificate" for this song. Music historians like Cecil Sharp, who spent years trekking through the American South to document folk music, found versions of these lyrics as early as 1916. But it was already old then. Some researchers think it has roots in Scots-Irish ballads brought over by immigrants. You can hear echoes of it in "The Wagoner’s Lad" or "Rye Whiskey." It’s a bit of a Frankenstein’s monster of folk stanzas.

The version most of us recognize today—the slow, waltzing, slightly mournful one—shot to fame in 1951. The Weavers, featuring the legendary Pete Seeger, recorded it and it went straight to the top of the charts. Suddenly, a song that had lived in the hollows of North Carolina and Tennessee for generations was being played on radios in Manhattan and Los Angeles.

People loved it. It felt authentic. It felt "folk." But in the process of becoming a pop hit, it got cleaned up a little bit. The raw, jagged edges of the mountain versions were smoothed out for a suburban audience.

Breaking down the verses (The ones that aren't about meatballs)

Let’s look at what the song actually says. If you go back to the older recordings, like the one by Roscoe Holcomb or even the 1930s field recordings, the lyrics usually start with that iconic location:

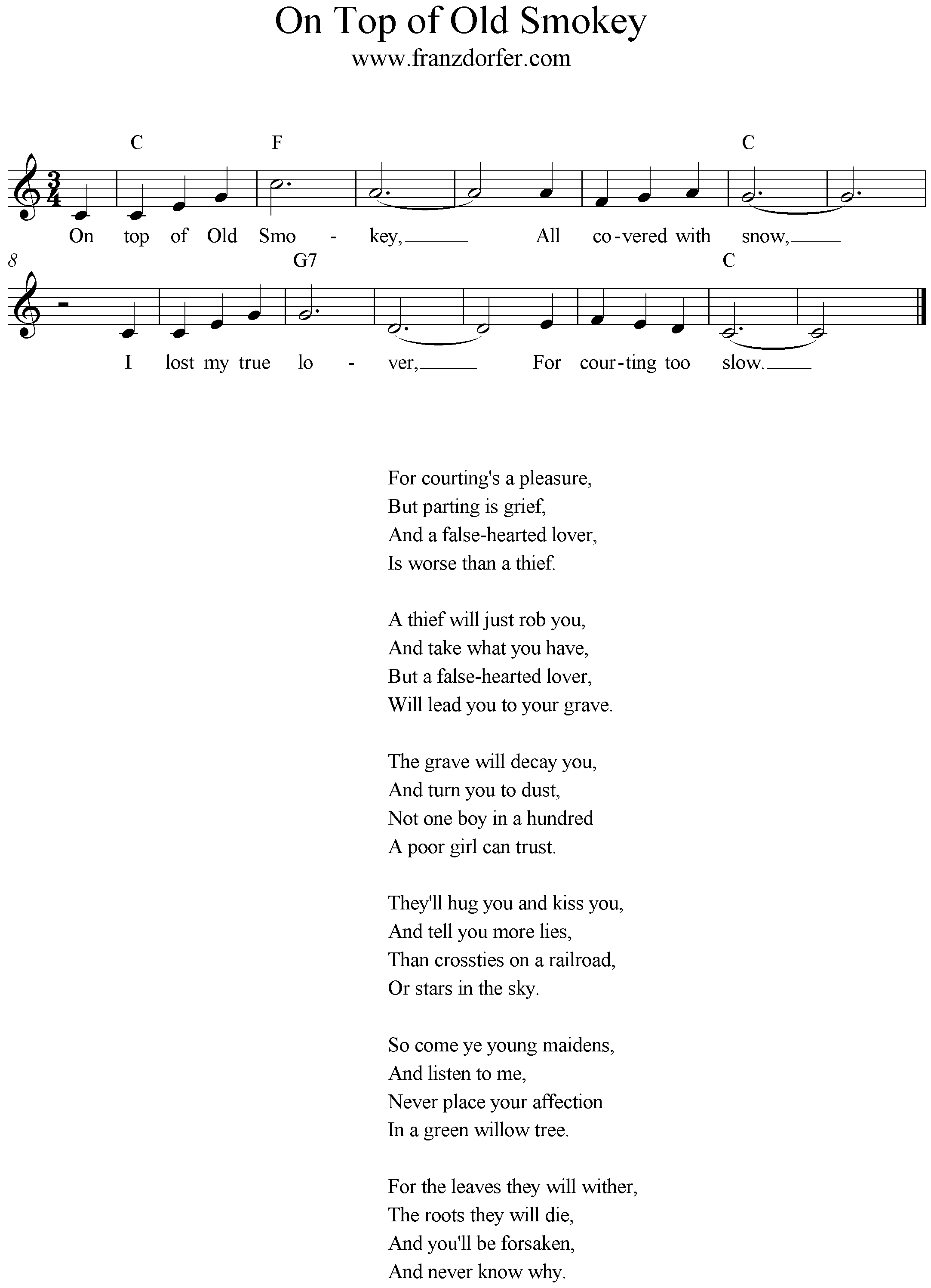

"On top of Old Smokey, all covered with snow, I lost my true lover, for a-courtin' too slow."

✨ Don't miss: Why the Cast of Hold Your Breath 2024 Makes This Dust Bowl Horror Actually Work

That's the hook. It sets the scene. But then it gets dark. Fast. The singer starts talking about how "a-courtin' is pleasure, but partin' is grief." They compare a false lover to a "thief" who will "steal your poor heart and then go their way."

There's this one verse that really hits: "They'll tell you they love you to give your heart ease, and as soon as your back's turned, they'll love who they please."

Man. That's cold.

Why the mountain matters

Why is it "Old Smokey"? Some people swear it refers to the Great Smoky Mountains on the border of North Carolina and Tennessee. Others think it’s just a generic term for any high, mist-covered peak. In folk music, geography is often symbolic. Being "on top" of the mountain represents isolation. You’re looking down at the town where your lover is probably currently cheating on you. You're high up, cold, and completely alone.

The 1960s parody that changed everything

You can't talk about the on top of old smokey lyrics without addressing the meatball in the room. In 1963, Tom Glazer released "On Top of Spaghetti."

"On top of spaghetti, all covered with cheese, I lost my poor meatball, when somebody sneezed."

🔗 Read more: Is Steven Weber Leaving Chicago Med? What Really Happened With Dean Archer

It was a novelty hit, and it was so successful that it basically nuked the original song's reputation for a generation. If you were born after 1960, you probably can't hear the melody without thinking about a meatball rolling out the door and under a bush. It’s a weird quirk of cultural history. A deeply sad, 100-year-old ballad about the agony of human betrayal was turned into a song about pasta by a guy who specialized in children's records.

Honestly, it's a testament to how catchy the melody is. It’s a simple, descending line that stays in your head forever. Even when you're singing about "mush," the underlying sadness of the tune still hangs around in the background.

Real experts and different versions

If you want to hear the "real" thing, you have to dig a bit. Look up the 1920s versions. The lyrical variations are wild. In some versions, the singer isn't just sad; they're angry. They warn other women—it’s often sung from a female perspective in older traditions—to never trust a man with "dark blue eyes" or a man who "drinks rye whiskey."

Folklorist Alan Lomax captured some of these nuances. He noted that the song wasn't just a lament; it was a piece of social currency. In isolated mountain communities, these songs served as warnings. They were cautionary tales.

Does "Old Smokey" even exist?

There is a specific peak in the Great Smokies called Clingmans Dome, which was sometimes referred to as "Smoky," but the song likely predates the naming of specific tourist spots. It’s more about the feeling of the mountain. That blue haze. The "smoke" that sits in the valleys. It’s a mood.

Why the lyrics still resonate (Even if we're just humming)

We still sing this song because the core emotion hasn't changed in 200 years. Sure, we have dating apps now, but the feeling of being "ghosted" or realizing that someone you loved was just "courtin' for ease" is universal.

💡 You might also like: Is Heroes and Villains Legit? What You Need to Know Before Buying

The on top of old smokey lyrics tap into a very specific kind of American loneliness. It’s a big country. There’s a lot of empty space. And when you’re standing in that empty space thinking about someone who doesn't want you anymore, you’re basically living in that song.

It’s also incredibly easy to play. You only need three chords. C, F, and G7. That’s it. Because it’s so accessible, it became the "standard" for every kid learning guitar or banjo. And every time someone picks it up, they change a word here or a line there. That’s the "folk process." The lyrics aren't set in stone. They’re a living thing.

How to use this song today

If you’re a musician or just a fan of music history, don't just stick to the "meatball" version or the polite 1950s radio edit.

- Check out the Archive of American Folk Song. You can find field recordings that sound like they were recorded in a windstorm, but the raw emotion in the voices is incredible.

- Experiment with the tempo. The Weavers made it a bouncy waltz. Try playing it slow. Like, painfully slow. It turns into a haunting dirge that feels way more "Appalachian."

- Read the "Warning" verses. Look for the stanzas that mention "cuckoo" birds or "false-hearted lovers." They add a layer of grit that makes the song feel much more grown-up.

Basically, the on top of old smokey lyrics are a piece of our collective DNA. They tell a story of a time when your reputation and your heart were the only things you really owned. When someone took one of those things from you, you didn't post about it on Instagram. You climbed a mountain and sang about it until the snow covered your tracks.

To really get the most out of this classic, try listening to the version by Gene Autry for a country-western vibe, or find the Roscoe Holcomb recording for that "high lonesome sound" that defines the genre. You’ll never look at a meatball the same way again.