You’ve probably seen the cover. It’s usually a grainy photo of a guy with a rucksack or some abstract, jittery font that looks like it was typed by someone who’d had way too much coffee. Maybe you read it in high school and thought it was a bit much, or maybe you read it at twenty-two while sitting in a Greyhound station and felt like your heart was exploding.

Being on the road with Jack Kerouac isn't just about a book. It’s a physical sensation.

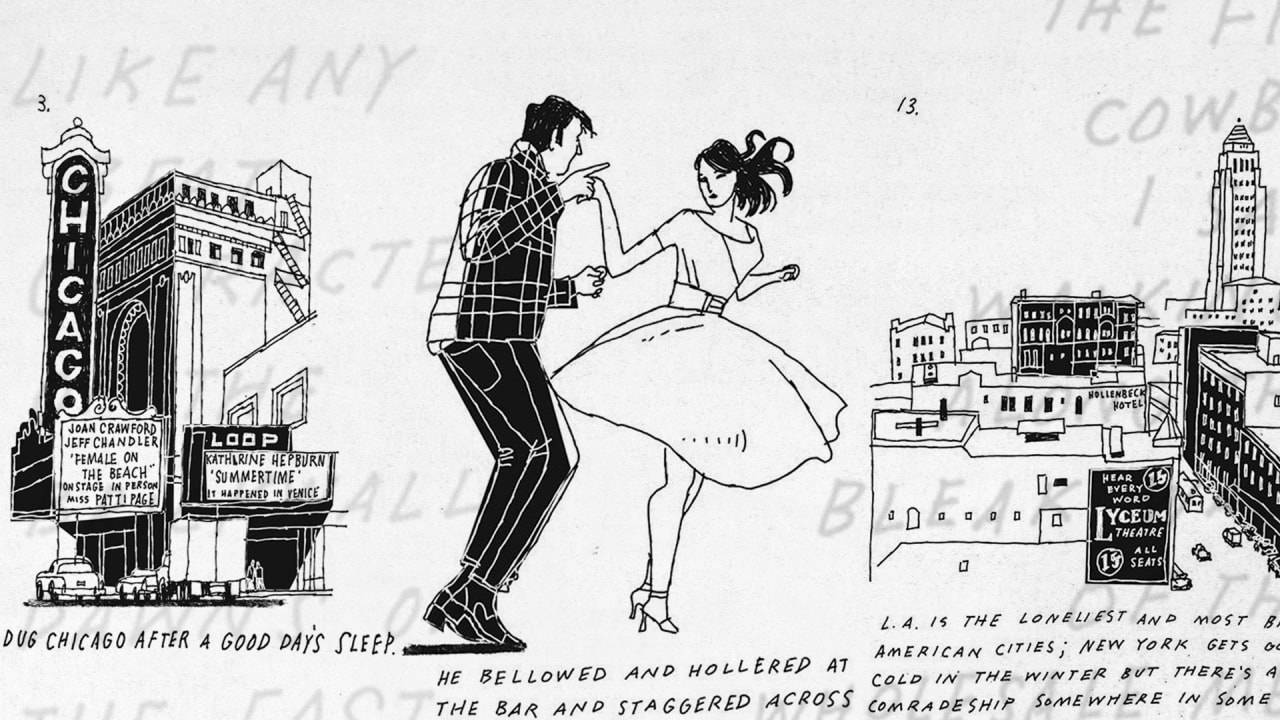

It’s the smell of diesel fumes in a Des Moines parking lot and the sound of Charlie Parker records spinning in a cramped New York apartment. When the book dropped in 1957, it didn't just sell copies; it changed how people moved through the world. Gilbert Millstein wrote that famous review in the New York Times, calling it a "historic occasion," and he wasn't exaggerating. But honestly? The reality of how that book came to be—and what it actually says about Kerouac’s life—is a lot darker and more complicated than the "free spirit" myth we usually get.

The scroll, the speed, and the sheer exhaustion

Everyone talks about the scroll. You know the legend: Jack Kerouac sat down in April 1951, fueled by nothing but coffee (and maybe some other substances, let’s be real), and hammered out the whole manuscript on a 120-foot roll of tracing paper in three weeks.

That’s mostly true. He did use a scroll because he didn't want to break his "spontaneous prose" flow by changing sheets of paper. He wanted the writing to feel like jazz.

But here’s what people get wrong. Kerouac didn't just manifest the story out of thin air in twenty-one days. He had been carrying notebooks for years. He’d been obsessively documenting his trips with Neal Cassady (the real-life Dean Moriarty) since 1947. The "scroll" was actually the result of years of mental marinating. It wasn't just a lucky whim. It was disciplined, frantic labor. If you’ve ever seen the original scroll—which billionaire Jim Irsay bought for over $2 million—you can see the edits. You see the sweat.

It's a long, single-spaced monster of a document. No paragraph breaks. No margins. Just a wall of words that mirrors the relentless pace of a car barreling down a two-lane highway at 90 miles per hour.

📖 Related: Isaiah Washington Movies and Shows: Why the Star Still Matters

Who were these people, really?

The names were changed to protect the "innocent," though nobody in this circle was particularly innocent. Sal Paradise is Jack. Dean Moriarty is Neal Cassady. Carlo Marx is Allen Ginsberg.

When you’re on the road with Jack Kerouac, you’re actually witnessing a very specific, very brief window of post-war American history. These weren't hippies. The hippies came later and borrowed the aesthetic. These were the Beats. They were looking for "It"—that elusive moment of spiritual peak or pure presence.

Neal Cassady was the engine. He was a guy who could talk a mile a minute, steal a car, find a party, and break three hearts before sunrise. Kerouac was the observer. He was the one sitting in the back seat with a notebook, trying to capture the lightning. It’s a weirdly lonely book for something so focused on friendship. You can feel Jack’s exhaustion. He’s following this manic energy that he knows he can’t sustain, and that tension is what makes the prose vibrate.

Why the 1950s hated and loved it

Imagine the 1950s. Eisenhower is in the White House. Everyone is moving to the suburbs. Everything is supposed to be beige, safe, and quiet.

Then comes this book about guys who don't want jobs, don't want mortgages, and definitely don't want to be quiet. They want to drink, listen to "bop" music, and talk about God in the middle of a roadside diner. It was a middle finger to the American Dream that actually ended up becoming a different kind of American Dream.

Critics were divided. Some thought it was a masterpiece. Others, like Truman Capote, famously quipped, "That's not writing, it's typing."

👉 See also: Temuera Morrison as Boba Fett: Why Fans Are Still Divided Over the Daimyo of Tatooine

Capote was being a jerk, but he touched on something. Kerouac’s style—this "spontaneous prose"—felt messy to the old guard. They didn't get that the messiness was the point. Life is messy. Road trips are messy. If you polish it too much, you lose the grit of the asphalt.

The dark side of the white lines

We shouldn't romanticize this too much. Living on the road with Jack Kerouac in real life was probably a nightmare.

- The poverty was real. They weren't "glamping." They were starving, hitchhiking in the rain, and sleeping on floors.

- The collateral damage. The women in the book—and in real life—were often left behind. LuAnne Henderson (Marylou) and Carolyn Cassady (Camille) had to deal with the fallout of Neal’s chaos while the guys were out "finding themselves."

- The ending. The book ends on a somber note. Dean is shivering in a doorway in New York, and Sal is leaving him behind. It’s not a "happily ever after." It’s a "we’re getting older and this can’t last" ending.

Kerouac himself struggled with the fame that followed. He was a shy, Catholic boy from Lowell, Massachusetts, who loved his mother. Suddenly, he was the "King of the Beats." He hated the label. He spent his later years drinking heavily and distancing himself from the very counterculture he helped create. By the time he died in 1969, he was living a life that looked nothing like the sprawling adventures of Sal Paradise.

The actual route: A geography of longing

If you tried to follow the map today, you’d find a different country, but the bones are the same.

- Route 6: This was the big one. Jack tried to hitchhike all the way across it and realized, famously, that he was "stuck" because he didn't plan well.

- Denver: The meeting ground. This is where the energy of the West met the intellect of the East.

- San Francisco: The "end" of the road, where the land stops and the jazz takes over.

- Mexico City: The final act. This is where the book shifts into a different gear—noisier, hotter, and more hallucinatory.

How to actually read it today

If you want to understand what it means to be on the road with Jack Kerouac, don't read it like a textbook. Read it for the rhythm.

Listen to the words. There are passages about the "purple dusk" over the Mississippi or the "great raw bulge" of the mountains that read more like poetry than fiction. Kerouac was obsessed with sound. He wanted his sentences to have the "swing" of a saxophone solo.

✨ Don't miss: Why Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy Actors Still Define the Modern Spy Thriller

Don't worry if you get bored during the parts where they’re just sitting around a house in Long Island. Life on the road has lulls. The boredom makes the "highs"—the 100 mph drives and the neon-lit nights—feel more earned.

Moving beyond the myth

So, what’s the takeaway? Is it just a book for college kids who want to quit their jobs?

Not really. It’s a book about the American restless spirit. We are a country of immigrants and pioneers, people who are always looking for something better just over the next hill. Kerouac captured that better than almost anyone else in the 20th century.

But he also showed the cost of that restlessness. You can’t run forever. Eventually, the road ends at the ocean, and you have to turn around and face yourself.

Actionable steps for the modern traveler

If the spirit of the road is calling you, but you don't want to end up like a broke Beatnik in 1952, here is how you channel that energy today:

- Ditch the GPS for an hour. Pick a direction and drive. Stop at the diner that looks like it hasn't been renovated since 1978. Talk to the person behind the counter. Kerouac’s best scenes came from his curiosity about strangers.

- Keep a physical journal. There is something about the tactile act of writing on paper—at a picnic table, in a bus station, or in the passenger seat—that forces you to notice details you’d miss on a phone.

- Listen to the soundtrack. Put on some Thelonious Monk or Dexter Gordon. That’s the "click" Kerouac was trying to emulate. Understanding the music helps you understand the meter of his writing.

- Read the "Original Scroll" version. If you've only read the standard 1957 edition, track down the version published in 2007. It uses the real names and has a rawer, more propulsive feel that the original editors scrubbed away.

- Acknowledge the "Stay." The road is only meaningful if you have something to come back to. Kerouac’s tragedy was that he never quite found his footing between the movement and the stillness. Find your balance.

The road is still there. It's wider now, more crowded, and lined with more franchises, but the "vastness of the sky" Jack wrote about hasn't changed. You just have to be willing to look up.