You see the trench coat. You hear the whistle. "The Farmer in the Dell" starts echoing through a West Baltimore alley, and suddenly, the toughest corner boys in the world are scattering like birds. It’s been decades since The Wire first aired, but Omar on the Wire remains a ghost that haunts the American psyche.

Honestly, he shouldn't work. On paper, Omar Devone Little is a walking contradiction that a network executive would have laughed out of a pitch meeting in the early 2000s. A gay, stick-up artist who robs drug dealers, never swears, and takes his grandmother to church every fourth Sunday? It sounds like a gimmick. But it wasn't. It was the most human thing on television.

The Man With the Code

What most people get wrong about Omar is thinking he was just a "Robin Hood" figure. That's too simple. Robin Hood stole from the rich to give to the poor. Omar stole from the "players" to give to himself and his crew, but he did it with a moral clarity that the police and the politicians in the show couldn't even dream of.

"A man gotta have a code," he famously said.

This wasn't just a cool line. It was his survival strategy. In a city where the police were juking stats and the drug kingpins were murdering children, Omar's rules were the only thing that felt solid. He never put his gun on anyone who wasn't "in the game." If you were a "civilian"—a regular person just trying to buy groceries—you were safe. If you were a dealer with a stash? Well, that's just business.

The character was actually rooted in real Baltimore history. David Simon, the show's creator, drew inspiration from several real-life stick-up men, most notably Donnie Andrews. In fact, the real Donnie Andrews actually appeared in the show as an associate of Omar's. Remember that scene where Omar jumps from a fifth-story balcony to escape a hit squad? That actually happened to Andrews in real life—though he later joked that in reality, it was a six-story jump and he didn't even break a leg.

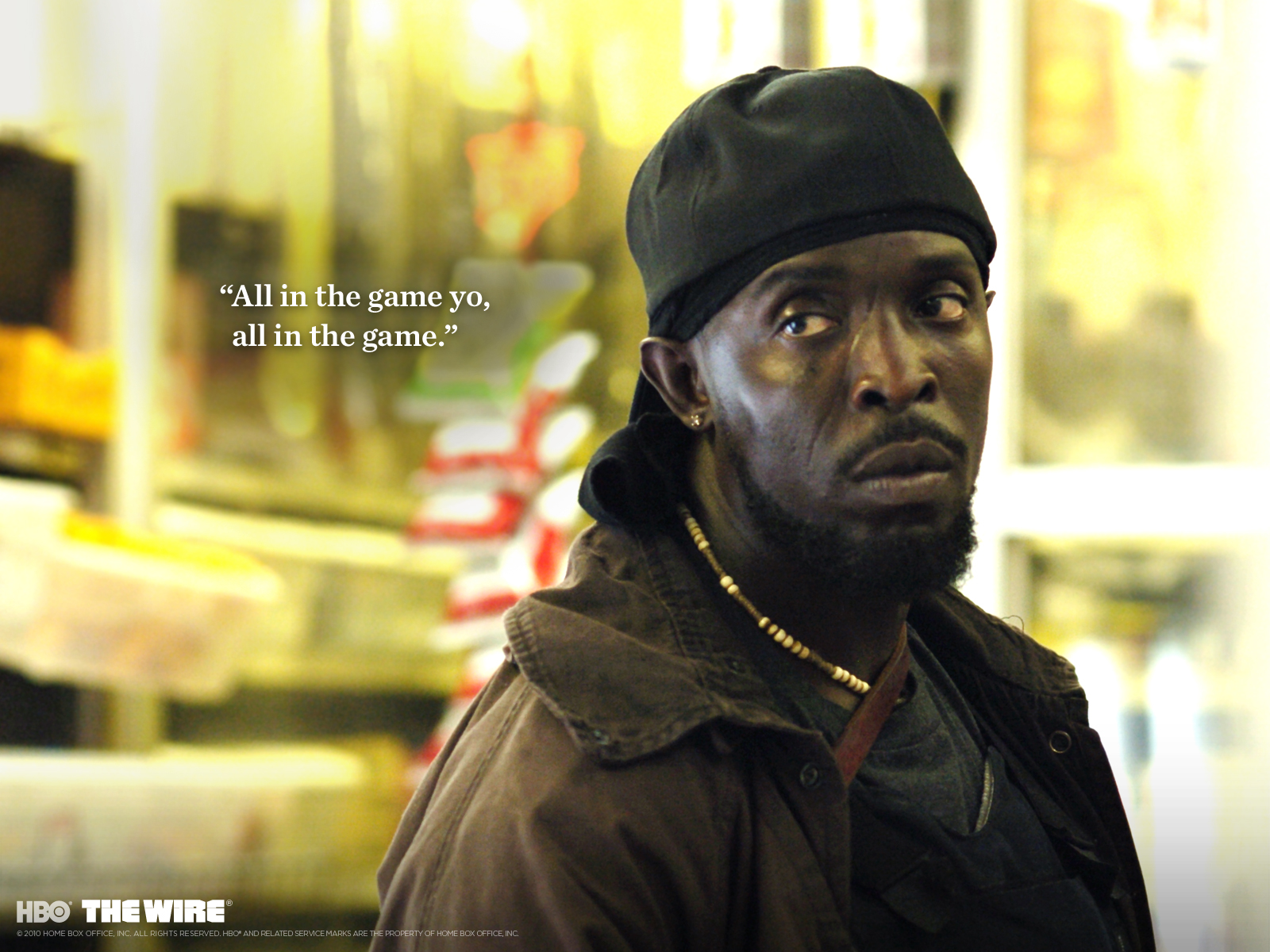

Why Michael K. Williams Made It Real

We have to talk about Michael K. Williams. Without him, Omar is just a well-written character. With him, Omar became a legend. Williams brought a "raw nerve" energy to the role because, as he admitted in several interviews before his passing, he wasn't really acting.

He was tapping into his own scars. Literally. That signature facial scar Williams had wasn't makeup; he got it in a bar fight in Queens on his 25th birthday. He lived in the projects. He knew the fear.

The Tragedy of the "Beast"

Williams spoke candidly about how the lines between him and Omar blurred. He started using drugs again during the filming of the show because he didn't know how to turn the character off. He called Omar a "beast" that he woke up every day. When fans saw him on the street, they didn't see Mike; they saw the shotgun-toting icon.

👉 See also: Cassie Steele Movies and TV Shows: Why We’re Still Obsessed With Manny Santos

It’s a heavy burden. Imagine being a sensitive, vulnerable artist while the whole world wants you to be the baddest man in Baltimore.

The Gay Icon Nobody Saw Coming

In 2026, we take queer representation for granted in media. But back then? Omar was revolutionary. He was the first time many viewers saw a Black man who was both hyper-masculine and openly gay.

His sexuality wasn't a "plot point." It wasn't something he struggled with or had a coming-out arc for. He just was. He loved his boyfriends—Brandon, Dante, Renaldo—with a tenderness that was often the only source of real affection in the entire series. When Brandon was tortured and killed by the Barksdale crew, it didn't just spark a subplot. It fueled a multi-season war of vengeance.

It changed how people saw masculinity. You could be the most feared man in the city and still be a man who loves other men. The show never made it a joke.

The Death That Still Stings

People are still mad about how Omar died.

He didn't go out in a blaze of glory. He wasn't taken down by a rival kingpin like Marlo Stanfield in a grand Western shootout. He was shot in the head by a little kid named Kenard while buying a pack of Newports in a corner store.

It was boring. It was sudden. It was perfectly The Wire.

The show was always about how the "system" doesn't care about your legend. To the world, Omar was a myth. To the medical examiner's office in the final season, he was just another body on a slab. They even mixed up his name tag with a white guy's. That’s the ultimate insult in a show that cares about the truth: in the end, the bureaucracy erases the individual.

How to Watch Omar Today

If you’re revisiting the series or (lucky you) watching it for the first time, pay attention to the silence. Omar doesn't talk as much as Stringer Bell or McNulty. He watches. He waits.

Pro-tips for the "Omar" experience:

- Watch the eyes: Michael K. Williams does more with a squint than most actors do with a monologue.

- Listen for the whistle: It’s a variation of "The Farmer in the Dell." The lyrics "The cheese stands alone" are a direct reference to Omar's isolation.

- Follow the Newports: His brand of choice is more than just a prop; it’s a recurring motif of his "civilian" needs clashing with his "warrior" life.

The reality is that Omar on the Wire is the heart of the show because he’s the only one who truly escaped the institutions. He didn't work for the cops. He didn't work for the gangs. He was the "cheese" that stood alone.

If you want to understand the impact of the character, don't look at the shootouts. Look at the scene where he testifies in court wearing a silk tie over his sweatshirt. He looks the lawyer in the eye and tells him they're exactly the same: "I got the shotgun, you got the briefcase. It's all in the game though, right?"

That's the whole show in one sentence.

To truly appreciate the legacy of Omar, you should start by re-watching Season 1, Episode 3 ("The Buys"), where he makes his first appearance. Pay close attention to how the camera treats him compared to the other gangsters; he is framed like a phantom, someone who exists in the shadows of a city that has already forgotten its own people. Once you've finished the series, look up Michael K. Williams' final interviews—they offer a heartbreaking but necessary perspective on the cost of bringing such a complex human being to life.