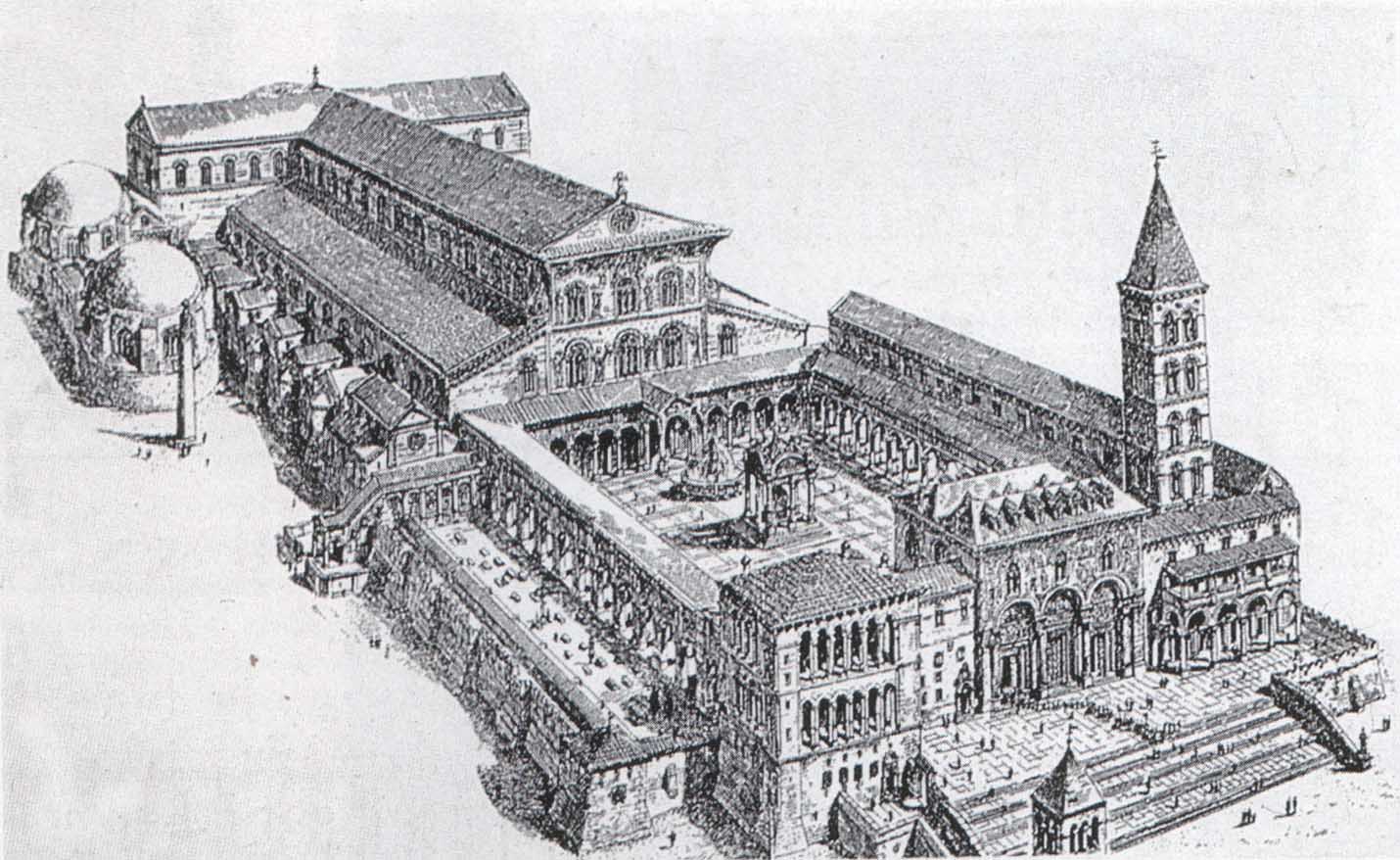

You’ve seen the photos of the Vatican. Huge dome. Massive colonnades. Swarms of tourists in St. Peter’s Square. That’s the "new" one, relatively speaking. But underneath that Renaissance marble lies a ghost. For over a thousand years, a completely different structure stood there. It was Old Saint Peter's Basilica, and honestly, it was arguably more chaotic, vibrant, and historically wild than the masterpiece Michelangelo helped finish.

It wasn't just a church. It was a massive covered cemetery, a diplomatic hub, and a literal construction site for centuries. When Constantine the Great decided to build it around 318 AD, he wasn't just being pious. He was making a massive political statement. He chose a spot on the Vatican Hill that was actually a nightmare for builders. It was a steep slope. Why bother? Because that’s where everyone believed the Apostle Peter was buried after being crucified upside down in Nero’s circus.

The Engineering Mess Nobody Talks About

Constantine’s engineers probably hated the assignment. To create a level surface for Old Saint Peter's Basilica, they had to move enormous amounts of earth and build a massive platform. This meant burying an existing pagan necropolis. They literally chopped the tops off old tombs and filled them with dirt to make the foundation. Imagine the sheer balls it took to just bury a Roman cemetery to make room for a new Christian one.

The result was a five-aisled barn of a building. It wasn't "pretty" by modern standards. It had a wooden roof that was a constant fire hazard. The walls were thin. But it was huge. It could hold thousands of people, and for the early Middle Ages, it was the center of the known world. Inside, the floors were cluttered. People didn't just pray there; they lived there. Pilgrims slept in the aisles. Merchants sold trinkets. It was loud, smelled of incense and unwashed bodies, and felt alive.

Charlemagne, Crowns, and Chaos

One of the most pivotal moments in Western history happened right in the nave of Old Saint Peter's Basilica. On Christmas Day in 800 AD, Charlemagne knelt before the altar. Suddenly, Pope Leo III dropped a crown on his head and declared him Holy Roman Emperor.

✨ Don't miss: The Rees Hotel Luxury Apartments & Lakeside Residences: Why This Spot Still Wins Queenstown

It was a total "gotcha" moment.

History nerds still debate if Charlemagne knew it was coming. Some say he was annoyed. Others think it was a staged PR stunt. Either way, it happened in the old basilica, not the one you visit today. The space was dripping with mosaics that shimmered in the candlelight, reflecting a world that was trying to rebuild itself after the fall of Rome. The "Confessio," the area right above Peter’s grave, was the focal point. It was surrounded by twisted "Solomonic" columns that people believed came from the Temple of Solomon in Jerusalem. They didn't—they were actually Greek—but the vibe was what mattered.

Why They Actually Tore It Down

By the 1400s, the old girl was tired. The south wall was leaning outward by over three feet. It was literally bulging. Imagine standing in a church and realizing the wall next to you is tilting toward the Tiber River. Not great.

Pope Nicholas V started thinking about a rebuild, but it was Pope Julius II—the "Warrior Pope"—who finally pulled the trigger. In 1506, he did the unthinkable. He started tearing down the holiest site in Christendom. People were horrified. Bramante, the lead architect, was nicknamed "Il Ruante" (The Destroyer) because he was so aggressive with the demolition. They didn't even move the bones or the art carefully at first. It was a mess.

🔗 Read more: The Largest Spider in the World: What Most People Get Wrong

But here is the thing: they didn't tear it all down at once. For about a hundred years, there was a "Frankenstein" church. Half of it was the ancient, crumbling Old Saint Peter's Basilica, and the other half was the rising, shiny Renaissance structure. They actually built a wall inside to keep the dust away from the high altar while they worked. You could go to Mass in the old section while hearing hammers and cranes echoing from the new section.

The Survival of the "Grotte"

If you go to the Vatican today, you can still feel the presence of the old church. You just have to go down. The Vatican Grottoes are essentially the "basement" created by the floor level of the new basilica being higher than the old one.

- You can see fragments of 8th-century mosaics.

- The tomb of Peter is still the anchor point.

- The foundations of Constantine's walls are still down there, acting as the literal bones of the current site.

Archaeologist Margherita Guarducci spent years in the mid-20th century analyzing the "Graffiti Wall" near Peter’s tomb. She found scrawls from ancient pilgrims saying things like "Peter is here." That’s the tangible link. Old Saint Peter's Basilica wasn't just a building; it was a protective shell for that specific spot.

What Most People Get Wrong About the Transition

A common myth is that the old church was "ugly" or "primitive." It wasn't. By the time it was demolished, it was a museum of a thousand years of art. It had Giotto frescoes. It had massive bronze doors. It had a courtyard (the atrium) with a giant pinecone fountain that Dante Alighieri even wrote about in the Divine Comedy. That pinecone? It’s still in the Vatican Museums today.

💡 You might also like: Sumela Monastery: Why Most People Get the History Wrong

The shift from the old to the new represented a shift in how the Church saw itself. The old basilica was a pilgrimage shrine—a place for the dead and the seekers. The new one was a palace of power, designed to show the Protestant Reformation that Rome was still the boss.

How to See the "Old" Version Today

You can't walk through it, obviously. But if you want to understand Old Saint Peter's Basilica, you have to look at the Church of San Paolo Fuori le Mura (St. Paul Outside the Walls). It was built around the same time and in a similar style. When you stand in the massive, open nave of San Paolo, you’re looking at a "twin" of what Saint Peter's used to be. It gives you that sense of scale—the long rows of columns leading the eye toward the tomb of an apostle.

Also, check out the "Sandro Botticelli" frescoes in the Sistine Chapel. In the background of The Punishment of Korah, he depicts the Arch of Constantine, but the architectural vibe is very much in line with the late-antique aesthetic of the old Vatican district.

Key Takeaways for History Buffs

- Foundation: Built on a literal graveyard, which is why the floor plan is so specific.

- Longevity: It stood for roughly 1,200 years. The "new" one has only been around for about 400.

- Artistic Loss: Hundreds of early medieval mosaics and frescoes were lost in the demolition.

- The Tomb: The entire reason for the building’s awkward location was the conviction that Peter was right there.

If you’re planning a trip to Rome, don't just look at the dome. Book a "Scavi Tour." It’s the only way to get under the floor and see the actual street level of the world Constantine built. You'll see the narrow alleys of the Roman necropolis and the massive brick supports that held up the original church. It’s claustrophobic, damp, and absolutely incredible.

Actionable Next Steps

- Book Scavi Tickets Early: The Ufficio Scavi only lets about 250 people in per day. You have to email them months in advance. Do it now.

- Visit San Paolo Fuori le Mura: It’s often empty compared to the Vatican and gives you the "Old St. Peter's" layout better than the current St. Peter's does.

- Look for the Pinecone: When you’re in the Vatican Museums, find the Cortile della Pigna. That bronze pinecone once sat in the courtyard of the old basilica and greeted pilgrims for centuries.

- Study the Grimaldi Drawings: Giacomo Grimaldi was a clerk who sketched the old church as it was being torn down. His drawings are the best visual record we have of what was lost.