You’ve probably seen the one with the kid sitting on a pile of soot. Or maybe the shot of the Monongahela Wharf looking like a crowded parking lot for steamships. Looking at old pictures of Pittsburgh PA isn't just a trip down memory lane; it’s basically an archaeological dig into the roughest, loudest, and most productive city that ever existed.

Pittsburgh wasn't always "livable."

Honestly, it used to be a nightmare of smoke and industry. But there is something about those grainy, black-and-white captures that hits differently than a high-def drone shot of the current skyline. They tell a story of a city that literally built the rest of the world.

The Smoke That People Actually Liked

It sounds crazy now. We spend so much time worrying about air quality and "green spaces." But if you go back to the early 1900s, smoke was basically a status symbol. People saw it as the "smoke of prosperity." If the sky was black, it meant the mills were running. If the mills were running, there was bread on the table.

Take a look at the archives from the Teenie Harris collection at the Carnegie Museum of Art. Charles "Teenie" Harris was a genius. He captured the Black experience in the Hill District better than anyone else in history. His photos show a neighborhood that was vibrant, crowded, and alive. You see jazz legends, sure, but you also see regular people dressed in their Sunday best, standing against a backdrop of row houses that haven't changed in a century.

The contrast is wild.

You have these incredibly sharp, well-dressed people navigating streets that were perpetually covered in a layer of fine, grey dust. It gives the photos a texture you just can't replicate.

📖 Related: Hairstyles for women over 50 with round faces: What your stylist isn't telling you

Why the 1940s Were a Turning Point

By the mid-1940s, the "Hell with the lid off" reputation had become a problem. Mayor David L. Lawrence and Richard King Mellon—who, let’s be real, basically owned the town—decided they’d had enough. This led to the first "Renaissance."

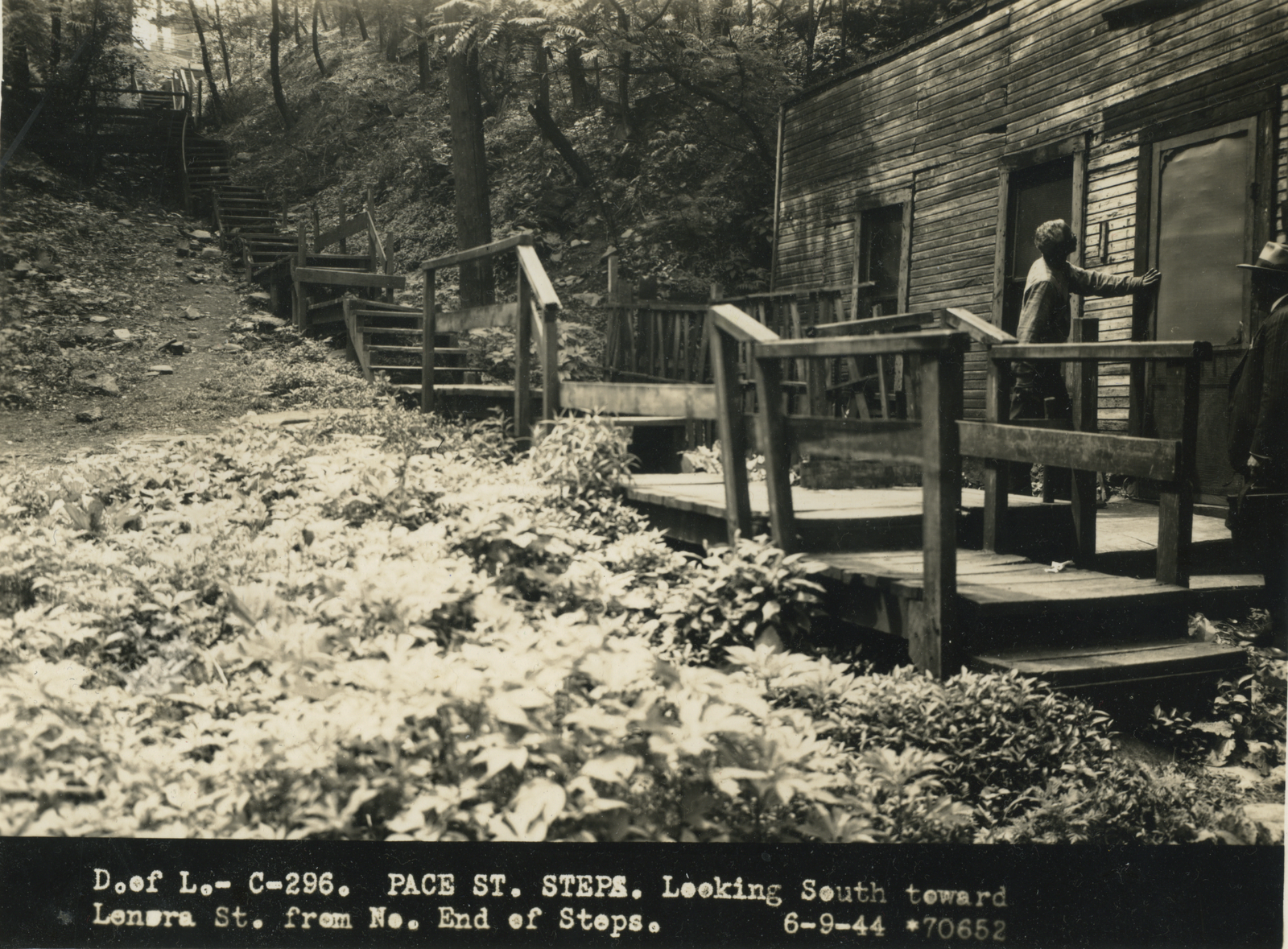

If you find photos from the late 40s, you start to see the transition. The smoke control ordinances started kicking in. Suddenly, you could see the buildings again. Before that, streetlights stayed on at noon. Imagine that. You’re walking to lunch and the sun is completely blocked out by carbon. Old pictures of Pittsburgh PA from this era often show the sheer scale of the cleanup. It wasn’t just a few power washers; they had to fundamentally change how people heated their homes and how factories operated.

The Lost Neighborhoods

We need to talk about the Point. Everyone knows the fountain. Everyone knows the park where the three rivers meet. But before the 1950s, the Point was a cluttered, industrial mess.

It was a tangle of railroad tracks and warehouses.

When you look at photos from the late 19th century, the tip of the Golden Triangle is barely recognizable. There were no manicured lawns. There was the Exposition Building, which was this massive, ornate structure where people went to see the latest technology. It eventually got torn down, like many things in Pittsburgh, to make way for "progress."

Then there’s the lower Hill District.

👉 See also: How to Sign Someone Up for Scientology: What Actually Happens and What You Need to Know

This is the painful part of the city’s photographic history. In the name of urban renewal, the city cleared out acres of homes and businesses to build the Civic Arena. Looking at photos of those demolished blocks is haunting. You see storefronts that had been there for fifty years just reduced to rubble. It reminds us that "progress" usually costs someone something.

The Steel Giants

You can't talk about old pictures of Pittsburgh PA without mentioning the mills. The Jones & Laughlin (J&L) plant on the South Side was a beast. It stretched for miles.

The photos of the mill workers are where the real grit lives. These aren't posed corporate shots. These are men with faces covered in grease, standing next to vats of molten iron that look like they're about to explode. Lewis Hine, the famous sociologist and photographer, took some incredible shots here. He was trying to show the human cost of labor.

- The scale: Look for photos that show the mills in relation to the houses. The homes were literally in the shadow of the stacks.

- The rivers: The water in these old photos looks like oil. It’s thick, dark, and full of barges.

- The incline: The Monongahela and Duquesne Inclines appear in almost every era. They are the one constant. In the 1880s, they were how the "hilltoppers" got to work without dying of exhaustion.

Where to Find the Real Stuff

If you're tired of seeing the same five photos on Pinterest, you have to go to the source. The Historic Pittsburgh website, hosted by the University of Pittsburgh, is the gold standard. They have thousands of high-res scans. You can zoom in and see the price of eggs on a grocery store window in 1912.

The Heinz History Center also holds a massive collection. They have the Detre Library & Archives, which is basically the attic of the city. You’ll find things there that aren't online—handwritten notes on the back of photos, identifying the specific people standing on a street corner in East Liberty.

Practical Steps for Collectors

Maybe you found a box of old photos in your grandmother’s attic in Brookline or Dormont. Don’t just leave them there.

✨ Don't miss: Wire brush for cleaning: What most people get wrong about choosing the right bristles

First, get them out of those "magnetic" photo albums from the 70s. The glue in those things is acidic and it will eventually eat the image. Use a flat spatula to gently pry them up. If they’re stuck, stop. Don't rip them.

Second, digitize them at a high resolution. I’m talking at least 600 DPI. A phone snap isn't enough if you want to preserve the detail.

Third, talk to the oldest person in your family right now. Sit them down with the photos. Record the conversation. A photo of a random street in Lawrenceville is just a photo, but a photo of the street where your great-grandfather ran a bakery is a legacy.

Finally, if you have photos that show unique perspectives of the city—not just the skyline, but everyday life in the neighborhoods—consider donating copies to the University of Pittsburgh’s Archives Service Center. They are always looking to fill the gaps in the city's visual record.

Pittsburgh has always been a city of layers. Every time a new building goes up, it sits on the bones of something else. Looking at old pictures of Pittsburgh PA lets you see those layers clearly. It’s a way to respect the people who worked 12-hour shifts in the heat so that we could have the city we do today. It’s not always pretty, but it’s ours.