If you’re driving through the bustling, tech-heavy streets of Fremont, California, you might stumble upon a white adobe building that feels like it dropped out of another century. That's Old Mission San Jose. Most people walk past the thick walls or take a quick selfie in front of the church and assume they’ve seen it. They haven’t. Honestly, what you see today is a strange, beautiful mix of a 1980s reconstruction and original 1797 foundations, and the story behind it is way more complicated than the "peaceful outpost" narrative we all learned in fourth grade.

It’s a survivor.

The site has been leveled by earthquakes, repurposed by gold seekers, and nearly forgotten by history. Today, it stands as a weirdly perfect metaphor for California itself: a layer cake of indigenous heritage, Spanish ambition, and modern preservation.

The 1868 Disaster and the Fake Church

For a long time, if you visited this spot, you weren't looking at a Spanish Mission at all. You were looking at a wooden parish church. In 1868, the massive Hayward Fault decided to remind everyone it existed. A violent earthquake basically pulverized the original adobe church, leaving the site in ruins. For over a hundred years, a "modern" Victorian-style wooden church sat on the property.

It wasn't until the early 1980s that a massive, $5 million community effort kicked off to bring back the original look. This wasn't some cheap facade job. They used authentic methods, making thousands of adobe bricks by hand. When you step inside the church today, you’re looking at a reconstruction so precise it feels eerie. The walls are four or five feet thick. It’s cool inside, even when the East Bay heat is pushing 90 degrees. That’s the thermal mass of the adobe doing the work, just like it did in the 1790s.

But here is the thing: the museum next door? That’s the real deal. It’s housed in the original convento, the only part of the mission structure that actually survived the 1868 quake. When you walk those floorboards, you’re touching the 18th century.

Life at Mission San Jose: It Wasn't a Postcard

We have to talk about the Ohlone people. Specifically the Chochenyo.

Mission San Jose wasn't just a church; it was a massive industrial and agricultural hub. At its peak around 1831, it was one of the most prosperous missions in the entire chain. We’re talking over 12,000 head of cattle and 13,000 sheep. But that prosperity came at a staggering human cost. The transition for the local indigenous population from a hunter-gatherer lifestyle to a rigid, European-style agricultural system was brutal.

✨ Don't miss: Finding Your Way: What the Map of Ventura California Actually Tells You

History isn't clean.

You’ll hear some folks talk about the "Golden Age" of the missions, but Father Narciso Durán, who ran the place for decades, was a complex figure. He was a musician who started a famous indigenous orchestra—some of their hand-written choir books are still in the museum—but he also oversaw a system that essentially stripped the Ohlone of their traditional culture. Disease, more than anything else, was the real villain. Measles and smallpox ripped through the cramped living quarters. If you visit the cemetery today, the silence there is heavy. It’s a place of mourning as much as it is a historical site.

The Gold Rush and the Mission's "Wild West" Phase

After the Mexican government secularized the missions in the 1830s, Old Mission San Jose went through a bit of an identity crisis. It wasn't a religious center anymore. It was basically a retail hub.

During the California Gold Rush, the mission was a crucial stop for miners heading from San Francisco to the Sierras. A guy named Henry Smith turned the mission buildings into a general store and a hotel. Imagine that for a second. Instead of Gregorian chants, you had dusty prospectors drinking whiskey and buying shovels in the same halls where padres once prayed.

The mission lands were eventually carved up and sold off. It’s a miracle the convento survived this era at all. It was used as a storage facility and a saloon at various points. It took the intervention of the Sisters of the Holy Family and later the Diocese of Oakland to realize that if someone didn’t step in, one of the most significant pieces of California history was going to be paved over for suburban housing.

Why the Architecture Actually Matters

The design of the reconstructed church is surprisingly minimalist. It’s "Mission Adobe," but without the flashy flourishes you see in places like Santa Barbara.

- The Reredos: The altar screen is a masterpiece of gold leaf and wood. It’s a replica, but it’s based on detailed sketches and descriptions from the original era.

- The Bells: There are four bells in the tower. Two of them are original. When they ring, you are literally hearing the same frequency that people in the valley heard in the early 1800s.

- The Floor: The tile work is purposefully uneven. It mimics the handmade nature of the original floor.

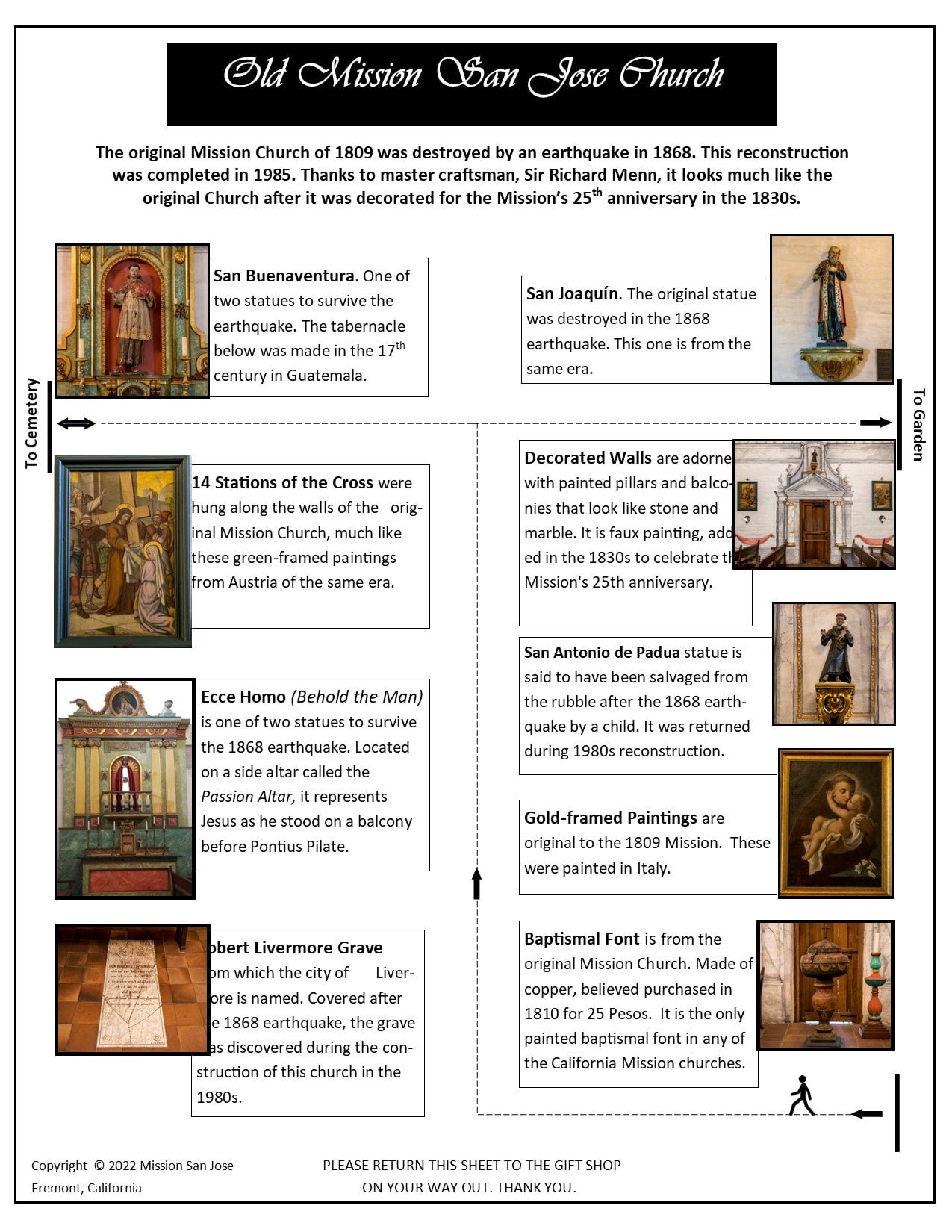

One detail most people miss is the baptismal font. It’s an original piece of hammered copper on a wooden base. It’s survived everything—the secularization, the earthquake, the neglect. It’s a small, physical link to the thousands of people who were brought into the mission system.

🔗 Read more: Finding Your Way: The United States Map Atlanta Georgia Connection and Why It Matters

Things to Look For in the Museum

The museum is tucked away, but it's where the real "ghosts" live.

- The Vestments: You’ll see silk robes embroidered with silver and gold thread that were brought over from Spain and Mexico. The contrast between these opulent clothes and the dirt-floor reality of the mission is jarring.

- The Musical Manuscripts: Look for the square-note sheet music. Father Durán’s choir was famous throughout Alta California. The fact that these papers survived the humidity and the rats for 200 years is insane.

- Agriculture Tools: There are old olive presses and tools that show just how much of a "company town" this place was.

The "Secret" Olive Grove

If you walk a bit away from the main buildings, you’ll find some of the oldest olive trees in California. These aren't just landscaping. They are the descendants of the original trees planted by the Spanish.

They still produce fruit.

There’s something sort of grounding about standing under a tree that was a sapling when the United States was barely a country. It’s one of the few places in the Bay Area where you can actually hear yourself think without the hum of the 880 freeway dominating your brain.

Practical Tips for Your Visit

If you’re actually going to head out to Fremont, don’t just show up at noon on a Saturday and expect a private tour.

The Mission is located at 43300 Mission Blvd. It’s right in the middle of a residential/commercial neighborhood, which catches people off guard. Parking is usually okay in the small lot or on the street, but check the parish schedule. It’s still an active church (Saint Joseph Terrace), so if there’s a wedding or a funeral, you won’t be getting into the main sanctuary.

The museum has a small admission fee—usually around $5 or $7. It’s worth it. That money goes directly into the massive seismic retrofitting and maintenance bills that come with owning a 200-year-old mud building.

💡 You might also like: Finding the Persian Gulf on a Map: Why This Blue Crescent Matters More Than You Think

Pro tip: Go in the late afternoon when the sun hits the white walls of the church. The light turns a warm, honey-orange color that is a photographer's dream. Then, walk across the street and grab some food in the Mission San Jose district. It’s got a very different "small town" vibe compared to the rest of Silicon Valley.

What We Get Wrong About the Name

Technically, it's Misión del Gloriosísimo Patriarca Señor San José.

People often confuse it with the city of San Jose. It’s not in San Jose. It’s about 15 miles north. When it was founded, it was named for Saint Joseph, but the city that grew up nearby took the name and ran with it. To make things even more confusing, there’s a "Mission San Jose" high school nearby that’s famous for being incredibly competitive.

If you tell a local you're going to "Mission San Jose," they might think you're going to a PTA meeting. Make sure you specify you're going to the Old Mission.

The Legacy of the Chochenyo Today

It’s easy to talk about the Ohlone in the past tense. Don’t do that. The Muwekma Ohlone Tribe is very much active in the Bay Area. For them, Old Mission San Jose isn't just a historic site; it’s a site of ancestral connection and, frankly, some pretty painful history.

In recent years, there has been a push to better represent the indigenous perspective in the museum. It’s not perfect, but it’s getting better. You’ll see more information now about the resistance—indigenous people didn't always go along with the mission system. There were runaways, there were revolts, and there was a constant, quiet struggle to keep their own traditions alive behind the mission walls.

Understanding the mission means holding two truths at once: it is a beautiful architectural achievement and a site of significant cultural loss.

Actionable Steps for Your Visit

To get the most out of a trip to this landmark, follow these steps rather than just wandering aimlessly:

- Start with the Museum: Do not go into the church first. Go through the museum in the convento. It sets the stage and gives you the context of the "real" history before you see the "reconstructed" beauty.

- Check the Cemetery: It’s small, but it’s one of the most poignant parts of the grounds. Read the names. Look at the dates. It brings the scale of the history down to an individual level.

- Support the Local Shops: The district surrounding the mission has survived because people care about the history. Buying a coffee or a meal nearby helps keep the area from being absorbed into the generic sprawl.

- Download a Field Map: The mission's own website often has PDF guides that explain the specific flora and fauna on the grounds. The gardens are filled with plants that have been there since the 1800s.

- Look for the "Cat Hole": In the original convento doors, look for the small holes at the bottom. The padres kept cats to deal with the inevitable rodent problems that come with storing tons of grain. It’s a tiny, human detail that makes the history feel real.

Old Mission San Jose remains a powerhouse of California history because it refuses to disappear. It has survived the earth literally opening up and swallowing it. It has survived being a Gold Rush bar. Today, it sits as a quiet, white-walled sentinel in the middle of one of the most high-tech regions on Earth, reminding us that everything we build is eventually just another layer of history.