The Gulf of Mexico is basically the beating heart of the U.S. energy economy, but honestly, it’s a lot weirder and more complicated than just "drilling for oil." You’ve probably seen the massive, city-sized platforms on the news, or maybe you remember the nightmare of 2010, but the day-to-day reality of oil in the Gulf of Mexico is a high-stakes game of technological leaps and geological guessing games. It isn't just a bunch of rigs sitting in the sun. It's an ultra-deepwater frontier where machines operate in pressures that would crush a submarine like a soda can.

Right now, the Gulf accounts for about 15% of total U.S. crude oil production. That’s roughly 1.8 to 1.9 million barrels a day. If you think that number is dropping because of the "green transition," you’d be wrong. Production has actually been hitting record highs recently. It’s a paradox. We talk about moving away from fossil fuels, yet the infrastructure in the Gulf is getting more sophisticated—and more expensive—than ever before.

The 20,000 PSI Problem

For a long time, we hit a wall. We knew there was oil deeper down, but the earth literally wouldn't let us have it. Deepwater drilling usually happens in a few thousand feet of water, but the "Paleogene" play involves drilling through miles of rock below the seafloor. The pressure down there hits 20,000 pounds per square inch (psi). To put that in perspective, most existing equipment was only rated for 15,000 psi. If you use standard gear, it fails. Spectacularly.

Chevron recently changed the game with their Anchor project. This is huge. They used "20K" technology—basically specialized kits, valves, and blowout preventers designed to handle that extreme force. This wasn't just a small upgrade; it was a multi-billion dollar bet. Because they cracked the 20K code, industry experts like those at Wood Mackenzie estimate that an additional five billion barrels of oil are now "reachable" that weren't ten years ago. It’s like finding a whole new oil field underneath the one we already used up.

People often assume the Gulf is a "mature" basin, which is industry speak for "running dry." That’s a myth. It’s only mature in the shallow parts. In the deepwater, we’re still in the early chapters.

Economics of the Deep

Why do companies keep pouring money into oil in the Gulf of Mexico when shale drilling in places like the Permian Basin is so much faster? It comes down to "decline rates."

✨ Don't miss: Online Associate's Degree in Business: What Most People Get Wrong

A shale well is like a firework. It starts with a massive bang, but within a year or two, the production drops off a cliff. You have to keep drilling and drilling just to stay in the same place. Gulf wells are different. They are marathons. A single deepwater platform can cost $5 billion to build, which is a staggering amount of capital to tie up. But once that platform is running, it produces massive volumes for decades. The "lifting cost"—the price to actually get a barrel out of the ground once the rig is built—is incredibly low.

- Shell’s Vito platform is a great example.

- They actually redesigned it to be smaller and more efficient than previous generations.

- By simplifying the design, they cut costs by about 70% compared to their original plan.

This shift toward "lean" platforms is why the Gulf remains competitive. It’s no longer about who can build the biggest rig; it’s about who can build the smartest one. BP’s Argos platform, which started up in the Mad Dog field, uses "digital twin" technology. They have a virtual version of the platform running in a computer that predicts when parts will break before they actually do. It’s basically sci-fi at sea.

The Environmental Scars and the Pivot

We can't talk about the Gulf without talking about the Deepwater Horizon. It changed everything. It wasn't just the environmental catastrophe, which was horrific, but it fundamentally shifted how the Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (BSEE) regulates the water.

Nowadays, the safety requirements are stiflingly intense. And honestly? They should be. Every single blowout preventer is monitored with a level of scrutiny that didn't exist in 2010. But there’s a new tension now. It’s not just about spills anymore; it’s about carbon.

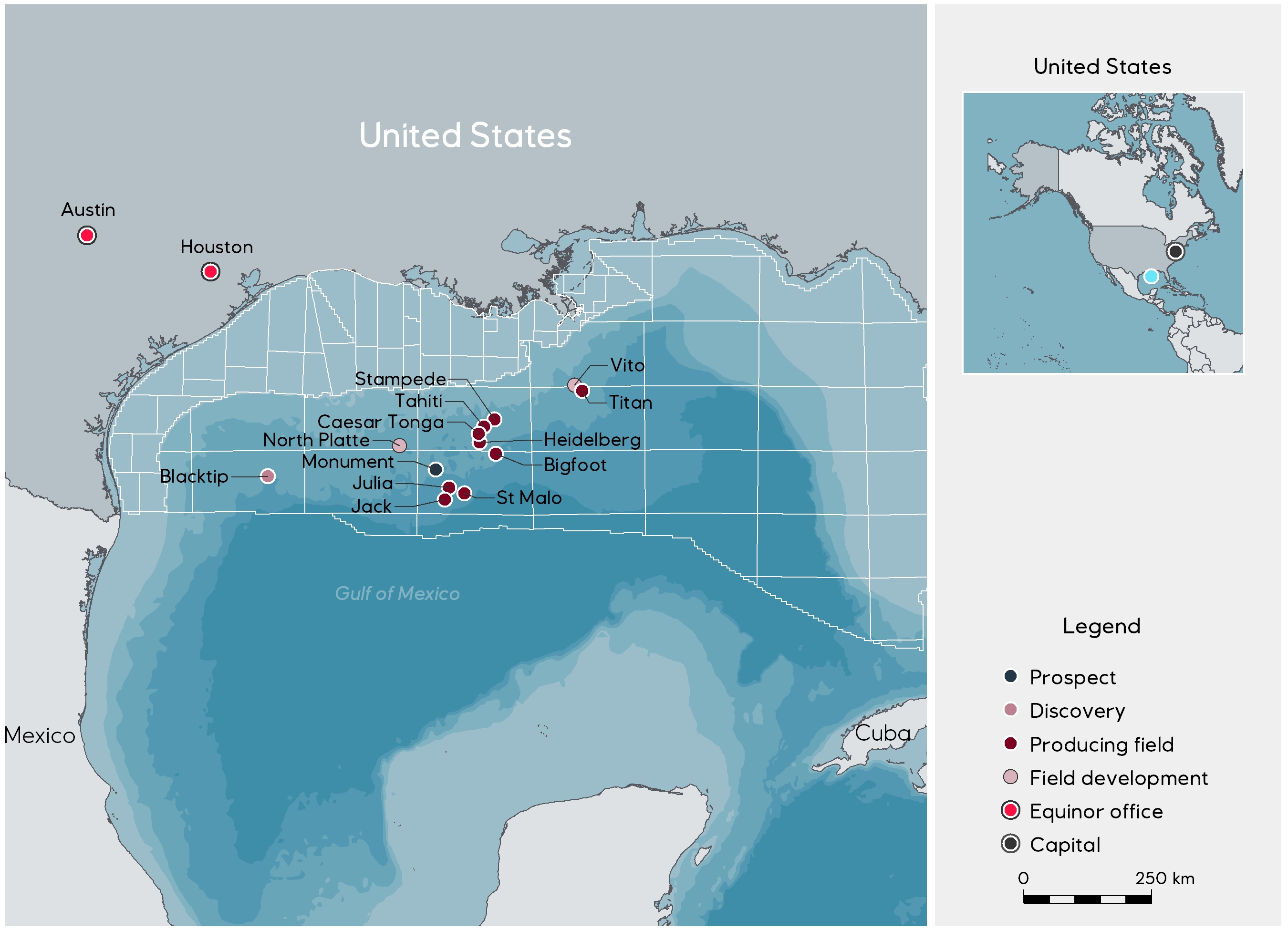

Some of the biggest players, like Equinor and TotalEnergies, are trying to brand Gulf oil as "low carbon" crude. That sounds like an oxymoron, right? Their logic is that because the production is so concentrated and efficient, the amount of emissions per barrel is lower than in places like Canada’s oil sands or even some onshore U.S. fields. Whether you buy that marketing or not, it’s the direction the industry is moving. They are trying to survive the ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) era by being the "cleanest" of the "dirty" options.

🔗 Read more: Wegmans Meat Seafood Theft: Why Ribeyes and Lobster Are Disappearing

What Happens When the Wells Run Dry?

Decommissioning is the elephant in the room. There are thousands of idle wells and hundreds of platforms that aren't producing anything anymore. They’re just sitting there, rusting. Federal law says companies have to plug these wells and remove the structures, but the cost is astronomical. We’re talking $30 billion to $100 billion in total liabilities over the next few decades.

There is a silver lining, though. Some of these old platforms are being turned into artificial reefs through the "Rigs-to-Reefs" program. It turns out that the massive steel jackets of these rigs are incredible habitats for red snapper and coral. If you pull the whole thing out, you destroy an entire ecosystem that grew up around it over 40 years. It’s a rare moment where the oil companies and the fishermen actually agree on something: sometimes leaving the junk behind is better for the ocean.

Geopolitics and Your Gas Tank

If a hurricane hits the Gulf, you feel it at the pump. It’s that simple. The concentration of refineries along the Louisiana and Texas coasts, combined with the offshore production, makes the U.S. energy supply incredibly vulnerable to weather.

But the Gulf is also a shield. Without the 1.8 million barrels a day from oil in the Gulf of Mexico, the U.S. would be significantly more dependent on imports from OPEC+ nations. This isn't just a business story; it's a national security story. During the price spikes of 2022, the steady flow from deepwater assets kept the market from spiraling even further.

The Surprising Tech: Not Just Drills

The most interesting stuff happening out there isn't the drilling—it’s the subsea robotics. We are getting to a point where we don't even need a "platform" on the surface for every field. Companies are moving toward "subsea tie-backs."

💡 You might also like: Modern Office Furniture Design: What Most People Get Wrong About Productivity

Basically, they pipe the oil from a new well along the seafloor for 20 or 30 miles to an existing platform. This saves billions. They use autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) that live in "garages" on the ocean floor. These robots do inspections and turn valves without a human ever getting wet. It’s a remote-controlled industry now.

Realistic Steps for Tracking the Industry

If you're looking to understand where this is going or perhaps looking at the sector from an investment or policy perspective, you can't just watch the oil price. You have to look at the "Lease Sales."

- Monitor the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) website for "Sale 261" type announcements. These auctions tell you exactly how much confidence companies have in the next 20 years. If the big players stop bidding on leases, the industry is winding down. For now, they’re still bidding billions.

- Follow the rig counts, but specifically "floaters" vs. "jack-ups." Floaters are the deepwater giants. If the floater count stays high, the long-term production is secure.

- Pay attention to the "Carbon Capture" permits. Many of these oil companies are applying to use the same geological formations that hold oil to instead pump $CO_2$ back into the ground. This could be the Gulf's second life.

The Gulf isn't going anywhere. It’s changing from a Wild West of "drill, baby, drill" into a highly digitized, ultra-high-pressure laboratory. It’s risky, it’s expensive, and it’s controversial, but it’s still the backbone of how the U.S. powers itself.

To stay informed, look into the quarterly earnings of companies like Hess or Occidental. They often discuss their Gulf assets with more transparency than the giant majors like Exxon. You'll see the real numbers behind the deepwater projects. Also, keep an eye on the "National Ocean Industries Association" (NOIA) for updates on how offshore wind is starting to compete for the same sea space as oil rigs. The overlap is starting to create some very interesting legal battles over who owns the rights to the wind above the oil.