It’s 1967. A young man named Edwin Hawkins is sitting in a basement in Oakland, California, trying to figure out how to make his youth choir sound a little less like a traditional church service and a little more like... well, the radio. He’s got an upright piano, a group of kids called the Northern California State Youth Choir, and a 100-year-old hymn. He isn't trying to change the world. He's basically just trying to sell enough copies of a custom-pressed album to fund a trip to a choir competition in Washington, D.C.

He didn't know he was about to create the oh happy day gospel song that would eventually sell seven million copies and win a Grammy. Honestly, the whole thing was kind of a fluke.

If you grew up in the church, you know the vibe of traditional gospel back then. It was heavy. It was formal. It was beautiful, but it was strictly "church music." But Hawkins? He was listening to the radio. He liked the breezy, sophisticated sounds of bossa nova and the jazz-inflected soul of the late 60s. He took an 18th-century hymn by Philip Doddridge, stripped away the stiff organ accompaniment, and added a Fender Rhodes piano and a funky, syncopated beat. The result was something the world hadn't really heard before: "Urban Contemporary Gospel."

Why This Version of Oh Happy Day Still Hits Different

You’ve probably heard a dozen versions of this song. Maybe you saw it in Sister Act 2 with a young Ryan Toby hitting those impossible high notes, or perhaps you’ve heard it belted out by Aretha Franklin or even Glen Campbell. But the original 1969 hit—which was actually recorded in 1967 but didn't blow up until a DJ in San Francisco named KSAN’s Bob McClay started spinning it—possesses a specific kind of magic.

The lead vocals by Dorothy Morrison are legendary. She wasn't just singing; she was testifying. Her voice has this raw, sandpaper-over-silk quality that makes the hair on your arms stand up. When she hits the line "He taught me how to watch, fight and pray," it doesn't sound like a Sunday School lesson. It sounds like a life-or-death survival guide.

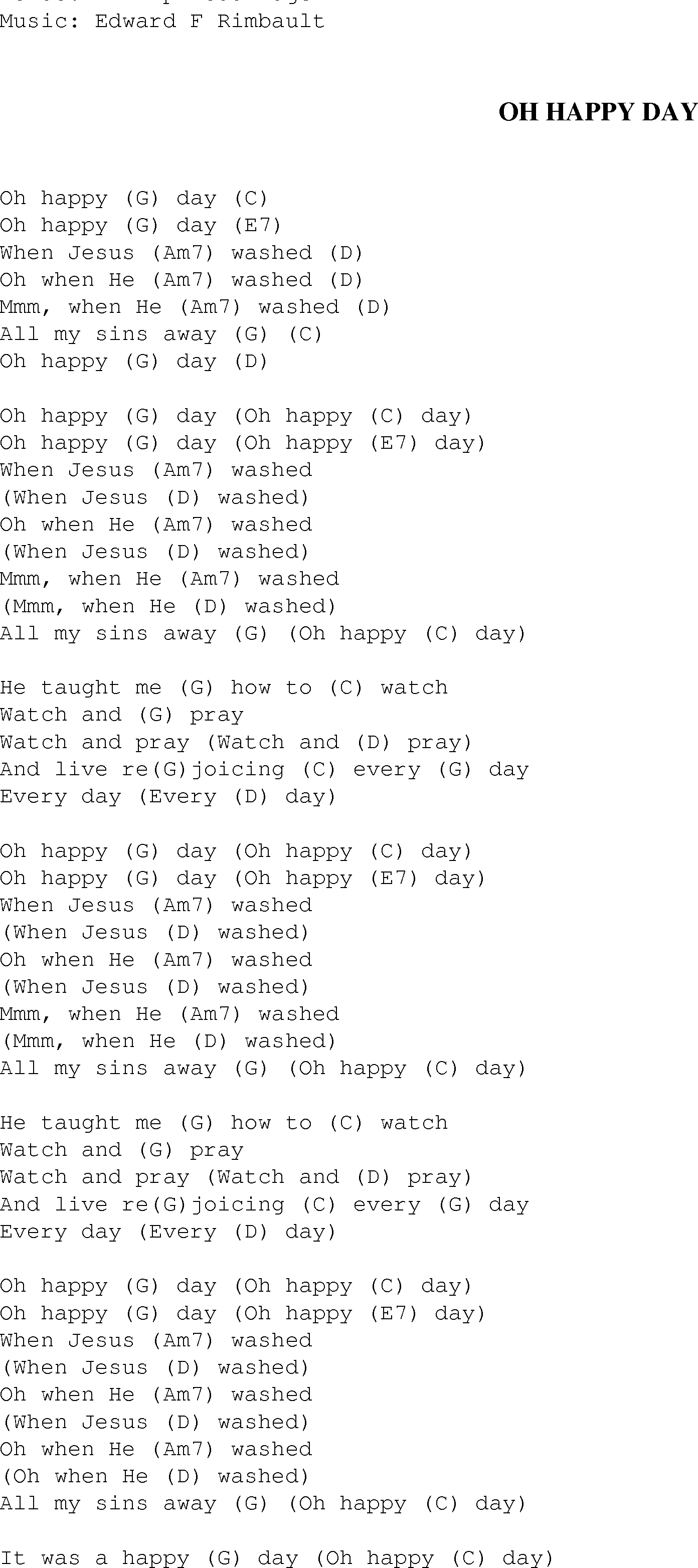

The structure of the song is actually pretty repetitive if you look at the sheet music. It’s a call-and-response masterclass. But the oh happy day gospel song isn't about lyrical complexity. It’s about the "groove." In the late 60s, "groove" was a secular word. Bringing that kind of rhythmic pocket into a sanctuary was scandalous to some people. Believe it or not, when the song first started climbing the Billboard charts, some more conservative black churches actually banned it. They thought it was "too worldly" because of the drums and the jazz chords.

👉 See also: Ted Nugent State of Shock: Why This 1979 Album Divides Fans Today

Imagine that. One of the most famous worship songs in history was once considered "devil music" by the people who should have loved it most.

The Accidental Recording That Went Global

The recording itself is famously "lo-fi." If you listen closely to the original track, you can hear the imperfections. It was recorded on a two-track machine at the Ephesian Church of God in Christ in Berkeley. There wasn't some high-end studio budget. There were no retakes. It was a live capture of a moment.

That raw quality is actually why it holds up today. In 2026, we are surrounded by AI-generated music and perfectly tuned vocals that sound like they were made in a lab. The Hawkins Singers’ version is the opposite of that. It’s human. You can hear the room. You can hear the collective breath of the choir.

The Cultural Impact: From Oakland to the Oscars

When the song hit #4 on the Billboard Hot 100 in 1969, it broke a massive barrier. It proved that gospel music could be commercially viable without stripping away its soul. It paved the way for artists like Kirk Franklin, Mary Mary, and Kanye West’s Sunday Service. Without Edwin Hawkins taking that risk, the landscape of modern R&B and Hip-Hop would look totally different.

Think about the artists who have covered it.

✨ Don't miss: Mike Judge Presents: Tales from the Tour Bus Explained (Simply)

- Elvis Presley (who was a massive gospel nerd, let's be real).

- Ray Charles.

- The Clark Sisters.

- Joan Baez (who performed it at Woodstock).

The oh happy day gospel song became a bridge. It bridged the gap between the sacred and the secular. It bridged the gap between black and white audiences during one of the most racially tense periods in American history. It’s one of those rare songs that feels just as home in a cathedral as it does at a backyard BBQ.

Misconceptions About the Origins

A lot of people think Edwin Hawkins wrote the song from scratch. He didn't. As I mentioned, the lyrics date back to the 1700s. The melody he used was actually based on a mid-19th-century version of the hymn. What Hawkins did was re-arrange it. He was the architect, not the mason.

Another common mistake? People often confuse the "Edwin Hawkins Singers" with the "Walter Hawkins Family." Walter was Edwin’s brother and a massive gospel star in his own right (famous for "Love Alive"), but "Oh Happy Day" belongs firmly to Edwin’s legacy.

The Technical Brilliance You Might Have Missed

If you’re a musician, pay attention to the piano work. Hawkins used a lot of major 7th and minor 9th chords—colors that were common in jazz but rare in church music at the time. This gave the song a "shimmer" that felt modern.

And then there's the tempo. It’s a slow burn. It starts with just the piano and the lead, building layers until the full choir explodes. That "build" is the secret sauce. It creates an emotional crescendo that is almost impossible not to react to. Even if you aren't religious, the sheer kinetic energy of 50 voices hitting that final chorus is a physical experience.

🔗 Read more: Big Brother 27 Morgan: What Really Happened Behind the Scenes

How to Truly Appreciate the Song Today

To get the most out of this piece of history, don't just stream it on a tinny phone speaker. Do this instead:

Find a high-quality version of the 1969 Let Us Go into the House of the Lord album. Put on some decent headphones. Listen for the way Dorothy Morrison slides into her notes. Listen to the handclaps—they aren't perfectly on the beat, and that’s why they feel so good.

The oh happy day gospel song isn't just a relic of the hippie era. It’s a testament to the idea that tradition can be updated without being disrespected. It teaches us that sometimes, the "mistakes" or the "accidents"—like a local choir record getting picked up by a pop station—are exactly what the world needs to hear.

Actionable Next Steps for Music Lovers and History Buffs

If you want to go deeper into the world that created this masterpiece, here is how you should spend your next few hours of musical discovery:

- Listen to the "Love Alive" series by Walter Hawkins. If you liked the vibe of Oh Happy Day, this is the natural evolution. It’s more polished but retains that deep, soulful Oakland roots feel.

- Watch the documentary 'Summer of Soul'. It features incredible footage of the era and explains the intersection of gospel, soul, and politics that made "Oh Happy Day" a hit.

- Compare the versions. Play the 1967 Edwin Hawkins version back-to-back with the Sister Act 2 version. Notice how the 90s version leans into hip-hop swing while the 60s version stays rooted in a Latin-influenced soul groove.

- Research the "COGIC" (Church of God in Christ) influence. This denomination is the bedrock of modern American music. Almost every major soul singer from Sam Cooke to Marvin Gaye came out of this tradition. Understanding the COGIC sound is key to understanding why "Oh Happy Day" sounds the way it does.

The story of this song is a reminder that you don't need a million-dollar studio to make something that lasts forever. You just need a good arrangement, a lot of heart, and the courage to play a hymn like it's a pop song.