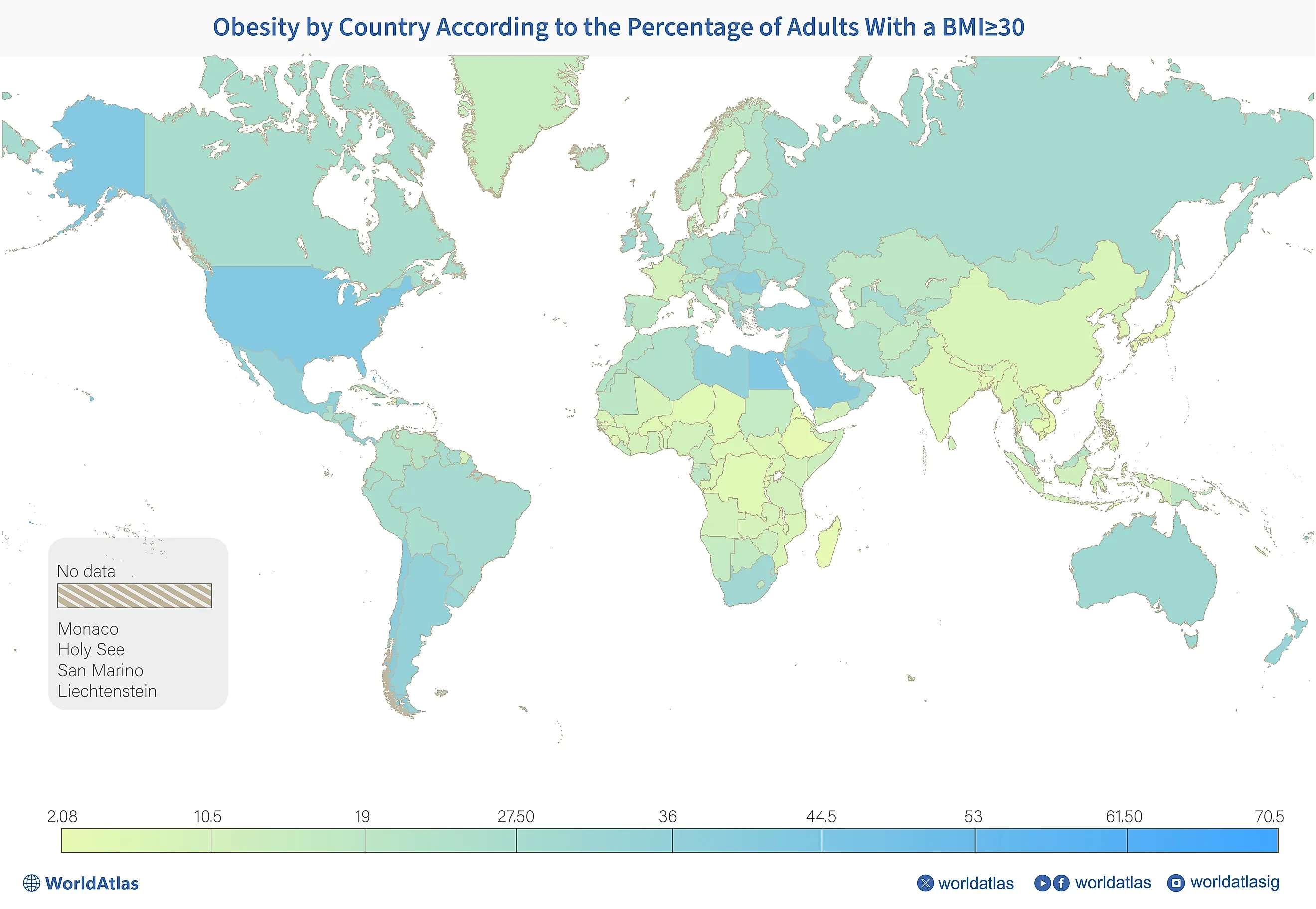

If you look at a map of the world, you might assume you know where the highest rates of weight-related health issues are. You're probably thinking of the United States. Maybe the UK. Honestly, that’s what most people assume because of the "Western diet" narrative we've been fed for decades. But if you actually dig into the latest obesity ranking by country, the reality is a lot more complex, and frankly, a bit startling. The top of the list isn't dominated by the G7 nations. It’s dominated by tiny island nations in the Pacific and countries in the Middle East that have seen their traditional lifestyles vanish almost overnight.

Weight isn't just about willpower. It’s about infrastructure.

According to data from the World Health Organization (WHO) and the NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC), we are looking at a global shift where over one billion people are now classified as living with obesity. That happened way faster than most scientists predicted. In 1990, the number was significantly lower. Now? It’s a full-blown crisis that looks different depending on whether you’re in Nauru or New York.

The Pacific Island Paradox

It’s wild. If you pull up an obesity ranking by country, the top ten spots are almost exclusively occupied by Pacific Island nations like Nauru, Cook Islands, and Palau. In Nauru, some estimates suggest that nearly 60% of the adult population is obese.

Why? It isn’t just about "eating too much." It’s history. These islands used to rely on fishing and local agriculture. Then came the 20th century. High-calorie, low-nutrient imported foods—think canned meats like Spam, refined flour, and sugary sodas—became the staple. Because these islands are remote, fresh produce is often prohibitively expensive. When a bag of apples costs more than a week’s supply of instant noodles and processed meat, the biological outcome is predictable.

Genetics might play a role, too. There's this "thrifty gene" hypothesis that suggests some populations are biologically predisposed to store fat more efficiently to survive periods of famine. When you drop a population with that genetic makeup into a modern environment of endless processed calories, the health metrics skyrocket. It’s a perfect storm of biology and bad trade deals.

Where the United States Actually Sits

You’ve probably heard people call America the "fattest nation on earth."

✨ Don't miss: High Protein in a Blood Test: What Most People Get Wrong

That’s actually factually incorrect. In the global obesity ranking by country, the U.S. usually lands somewhere around the 10th to 15th spot, depending on the specific year of the study and the age groups being measured. Don't get me wrong—the numbers are still staggering. More than 40% of American adults are obese. That has massive implications for the healthcare system, specifically regarding Type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

But the American experience is deeply tied to geography and income. If you live in a "food desert" in the Deep South, your access to affordable, fresh food is basically zero. You’re navigating an environment designed for cars, not people. Walking to the store isn't an option. This "obesogenic environment" is the primary driver. It’s not that Americans suddenly lost their self-control in the 1980s; it’s that the food system changed. High-fructose corn syrup started appearing in everything from bread to salad dressing.

The Middle East and the Rapid Wealth Gap

Kuwait, Jordan, and Saudi Arabia are high on the list. This is a relatively recent development.

The rapid urbanization in the Gulf states changed everything. You have extreme heat for much of the year, which makes outdoor exercise nearly impossible. Combine that with a massive influx of Western fast-food chains and a culture that prizes hospitality—which often centers around large, calorie-dense meals—and you see why the obesity ranking by country shows such high numbers in this region.

In Kuwait, for example, the obesity rate for women is particularly high. Researchers point to social norms and limited access to female-only gyms or safe outdoor spaces for exercise as contributing factors. It’s a reminder that health data is always a mirror of a country's social and cultural restrictions.

The "Thin" Nations and the Rise of Malnutrition

On the flip side, countries like Vietnam, Japan, and South Korea consistently rank at the bottom of the obesity scale.

🔗 Read more: How to take out IUD: What your doctor might not tell you about the process

Japan is a fascinating case. They have the "Metabo Law," which actually requires companies and local governments to measure the waistlines of citizens aged 40 to 74 during their annual check-ups. If you exceed certain limits, you’re given nutritional guidance. While it sounds extreme to Western ears, it reflects a society that views weight as a collective public health issue rather than just a personal failure. Plus, the traditional Japanese diet is naturally lower in fats and higher in fish and fermented foods.

However, there's a dark side to these low rankings. In some African and Southeast Asian nations, low obesity rates aren't a sign of "fitness"—they are a sign of persistent food insecurity. We are now seeing a "double burden" of malnutrition. This is where a single country (or even a single household) struggles with both undernutrition (stunting and wasting) and obesity simultaneously. This happens when cheap, junk food is the only thing available to people who are otherwise living in poverty.

Why BMI is a Flawed Metric for Rankings

We use Body Mass Index (BMI) for these rankings because it's easy. It’s just weight over height squared. But honestly? It’s kind of a mess.

BMI doesn't distinguish between muscle and fat. It doesn't account for bone density. More importantly, it doesn't account for where you carry your fat. Science has shown that visceral fat (the stuff around your organs) is much more dangerous than subcutaneous fat (the stuff under your skin).

Different ethnic groups also have different "healthy" BMI thresholds. Research suggests that people of South Asian descent may face higher risks of diabetes at lower BMI levels than Caucasians. So, when we look at an obesity ranking by country, we have to acknowledge that we are using a 19th-century tool to measure a 21st-century problem. It’s a blunt instrument for a very nuanced biological reality.

The Economic Cost of the Rankings

This isn't just about how people look in a swimsuit. It’s about the money.

💡 You might also like: How Much Sugar Are in Apples: What Most People Get Wrong

The World Obesity Federation predicts that the global economic impact of overweight and obesity will reach $4.32 trillion annually by 2035 if trends continue. That’s nearly 3% of global GDP. We’re talking about lost productivity, increased healthcare costs, and the strain on social services.

Countries are starting to fight back with "sin taxes" on sugar-sweetened beverages. Mexico, which has struggled significantly with its ranking, implemented a soda tax in 2014. The results? A measurable drop in consumption. It’s a slow process, but it shows that policy can move the needle on these rankings over time.

Shifting the Perspective on Global Health

The most important thing to understand about the obesity ranking by country is that it’s a map of industrialization and trade.

As countries move from developing to developed, their physical activity levels drop and their consumption of ultra-processed foods climbs. We’re seeing this right now in parts of Africa and Latin America. The "Western" problem has gone global.

What can we actually do with this information? It’s not about shaming the countries at the top. It’s about looking at the systemic issues.

Actionable Insights for Navigating the Global Reality

- Audit your environment, not just your plate. If you live in an area with high obesity rates, recognize that your environment is likely working against you. Identify "walkable" pockets in your community or advocate for better local food access.

- Ignore the "Average" BMI. If you're looking at where you fit in your country’s ranking, consult a healthcare provider about a DEXA scan or waist-to-hip ratio measurements instead of relying solely on BMI. These provide a much clearer picture of your actual metabolic health.

- Watch the "Hidden" Sugars. The countries that rose fastest in the rankings are those where liquid calories (sodas, juices, sweetened teas) became a daily staple. Cutting liquid sugar is the single most effective "policy" change an individual can make.

- Support Local Food Infrastructure. The lowest-ranking countries (in terms of obesity) often have strong local markets and a culture of cooking at home. Supporting local farmers and reducing reliance on imported, ultra-processed goods is a direct way to combat the systemic drivers of the obesity epidemic.

- Advocate for Policy Changes. Look into how your local government handles school lunches and urban planning. The rankings only change when the "default" choice in a country becomes the healthy choice.

The global obesity crisis is a reflection of how we’ve redesigned the world to be convenient but sedentary. The numbers are a wake-up call, but they aren't destiny. By understanding the cultural and economic drivers behind these rankings, we can start making choices—both as individuals and as a society—that prioritize long-term vitality over short-term convenience.