Ever sat in one of those uncomfortable plastic chairs at a blood drive, sipping lukewarm juice, and wondered why the nurses get so excited when they see your chart says O-negative? It’s not just because you’re a nice person. It’s because the logistics of who an o blood group can donate to are actually the backbone of modern emergency medicine. If you're Type O, you're basically the "Swiss Army Knife" of human biology. But there is a massive catch that people usually forget.

Most people think about blood types like a simple matching game. You have A, you give to A. You have B, you give to B. It’s logical. It makes sense. But biology isn't always that clean. The reality of blood compatibility is a high-stakes game of molecular "friend or foe" played by your immune system every single second. When we talk about who an o blood group can donate to, we are really talking about the absence of things—specifically, the absence of antigens that would otherwise trigger a life-threatening attack inside a patient's veins.

The Universal Donor Myth vs. Reality

We’ve all heard the term "Universal Donor." It’s a catchy label. However, it specifically applies to O-negative blood, not every Type O person walking around. If you are O-positive, your "universal" status is a bit more restricted.

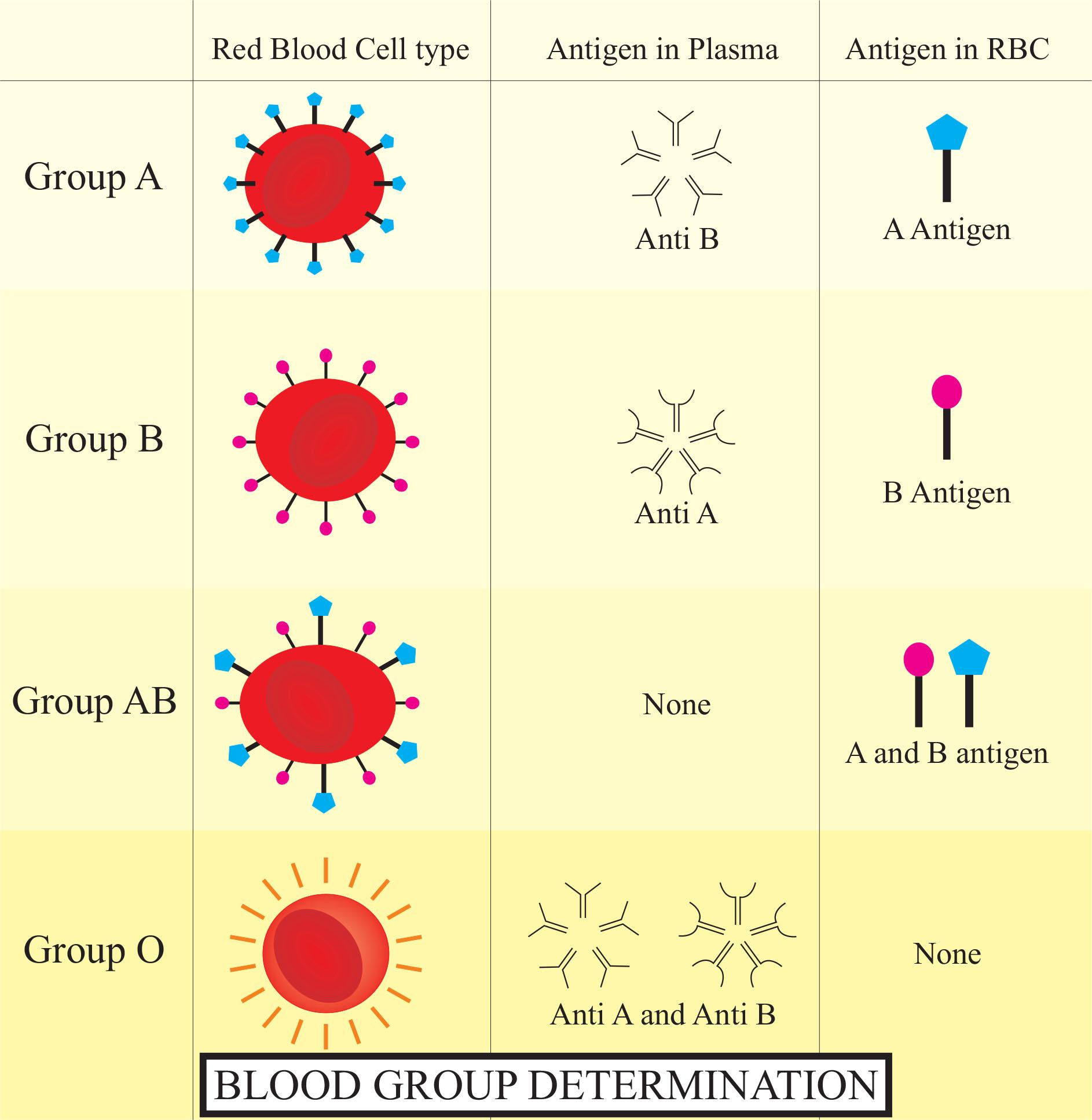

Here is the breakdown of the science without the textbook boredom. Your blood type is determined by tiny proteins called antigens that sit on the surface of your red blood cells. Type A has A antigens. Type B has B antigens. Type AB has both. Type O? It has neither. Because it lacks these "identifying flags," the immune system of a recipient doesn't recognize the blood as an intruder. This is why o blood group can donate to almost anyone in an emergency.

But then there's the Rh factor—that little plus or minus sign. If you’re O-positive, you have the Rhesus protein. If you give that blood to an O-negative person, their body might freak out. So, while O-positive is the most common blood type (around 38% of the population), it can only go to other "positive" blood types (A+, B+, AB+, and O+). O-negative, sitting at only about 7% of people, is the true "emergency room gold" because it can go to literally anyone, regardless of their Rh factor.

Why the ER Screams for Type O

Imagine a trauma center at 2:00 AM. A car accident victim rushes in. They’ve lost a lot of blood. There is zero time to "cross-match" or test the patient's blood type because they might bleed out in minutes. In that frantic, high-pressure window, doctors reach for O-negative blood.

They don't have to think. They don't have to wait for lab results. They just pump it in.

Karl Landsteiner, the guy who actually discovered these blood groups back in 1901, probably didn't realize he was uncovering the blueprint for modern trauma surgery. Before him, blood transfusions were a total gamble. People died constantly from "clumping" or agglutination because doctors were mixing incompatible types. Today, the fact that an o blood group can donate to all other types in a pinch is the reason why air ambulances and "Life Flight" helicopters carry O-negative coolers as standard equipment. It is the bridge between life and death while the lab catches up.

💡 You might also like: Finding Dr. Eric Brown Urologist: What to Know Before You Book

The "O-Positive" Power Player

Don't let the O-negative hype make you feel useless if you're O-positive. You are actually the most needed donor on the planet. Since O-positive is the most common blood type, it is also the most in-demand.

Think about it this way: Since roughly 1 in 3 people have your blood type, the hospital is constantly running out of it. An o blood group can donate to any positive blood type, which covers about 80% of the entire population. That is a massive demographic. When major surgeries happen—like heart bypasses or organ transplants—the sheer volume of O-positive blood required is staggering. Red Cross data consistently shows that while O-negative is for emergencies, O-positive is the workhorse that keeps the hospital system running on a daily basis.

The Weird Paradox of Type O

There is a funny irony here. While Type O is the most generous donor, they are the most "picky" recipients. If you are Type O, your plasma contains both anti-A and anti-B antibodies. This means your body will aggressively attack A, B, or AB blood.

- If you're O-negative: You can only receive O-negative. That's it.

- If you're O-positive: You can receive O-positive or O-negative.

It’s a bit of a raw deal, honestly. You can help everyone, but almost nobody can help you except your own kind. This is why blood banks get really nervous when Type O supplies run low—they can't just substitute something else if a Type O patient walks through the doors.

The Plasma Flip-Flop

Everything I just told you changes when we talk about plasma. This is where people get confused. In the world of red blood cells, Type O is the universal donor. But in the world of plasma, Type AB is the universal donor.

Why? Because plasma is the liquid part of your blood that contains antibodies. Type O plasma has all the antibodies (anti-A and anti-B), which makes it dangerous for people with A, B, or AB blood. Conversely, Type AB plasma has no antibodies, so it can be given to anyone. If you are Type O, your red cells are gold, but your plasma is actually the "universal recipient" equivalent. It’s a total 180-degree flip from the red cell rules.

Evolution and the "Original" Blood Type

There’s a long-standing debate in the scientific community about whether Type O is the "original" blood type of our ancestors. For years, the "Blood Type Diet" (which has mostly been debunked by actual nutritionists, by the way) pushed the idea that Type O people are "hunters" who need high-protein diets because Type O was the first to emerge.

The genomic reality is a bit more complex. Research published in Molecular Biology and Evolution suggests that the A allele might actually be the ancestral state, and Type O evolved as a mutation that provided a survival advantage. Specifically, Type O seems to offer some protection against severe malaria. This might explain why Type O is so prevalent in certain parts of the world—it was nature’s way of helping humans survive in mosquito-heavy environments.

Beyond the Basics: The "Golden Blood" Outlier

While we focus on how an o blood group can donate to others, we have to mention the rarest of the rare: Rh-null. This is often called "Golden Blood." It lacks all 61 possible antigens in the Rh system. There are fewer than 50 people in the entire world known to have it. While Type O is a universal donor for the general population, someone with Rh-null is the ultimate universal donor for anyone with rare Rh types. But for those 50 people, life is terrifying—they can only receive blood from each other, and there are only about nine active donors globally. Compared to them, being Type O feels like having a very common, very easy-to-manage superpower.

👉 See also: Donald Trump and Alzheimer’s: What the Medical Facts Actually Say

Practical Steps for Type O Donors

If you've confirmed you are Type O, your blood is a literal commodity. You shouldn't just show up and give a random "whole blood" donation if you want to be as helpful as possible. You should be strategic about it.

Double Red Cell Donation (Power Red)

Because the red cells are the most valuable part of Type O blood, many centers prefer you do a "Power Red" donation. They use a machine to take your red cells and then pump your plasma and platelets back into you. This allows you to give twice as many red cells in a single sitting. You’ll feel less wiped out afterward because you keep your fluids, and the hospital gets exactly what it needs from an o blood group can donate to scenario.

Check Your CMV Status

If you are O-negative and "CMV-negative," your blood is even more precious. CMV (Cytomegalovirus) is a common flu-like virus that most adults have been exposed to. It’s harmless to us, but it’s deadly to newborn babies. Hospitals specifically look for O-negative, CMV-negative blood for neonatal units. This is often called "Baby Blue" blood. If you fit this profile, you are essentially the only person who can provide safe transfusions for premature infants and babies requiring surgery.

Monitor Your Iron

Donating red cells frequently can tank your ferritin levels. Since Type O donors are hounded by blood banks to donate as often as possible (every 8 to 16 weeks), you have to be proactive. Eating spinach is fine, but if you’re a regular donor, talk to your doctor about an actual iron supplement. You can't save lives if you’re too dizzy to stand up.

The Bottom Line on Type O Compatibility

The logistics of who an o blood group can donate to aren't just trivia; they are a fundamental part of how we keep people alive in crises. If you are O-negative, you are the person the ER counts on when they don't have time to think. If you are O-positive, you are the person who ensures there's enough blood for the millions of people who share your type or have other positive types.

Understand your role in this system. If you haven't been typed, find out. If you are Type O, realize that you carry a resource that cannot be manufactured in a lab. There is no synthetic substitute for the A and B antigen-free cells living in your bone marrow.

Next Steps for Type O Individuals:

- Confirm your Rh factor: Don't guess. Check your medical records or a previous donation card to see if you are O+ or O-.

- Download a blood donor app: Use the Red Cross or local blood center app to track your "gallon" milestones and see where your blood is sent.

- Ask about Power Red: Next time you donate, ask the technician if you’re a candidate for a double red cell donation to maximize your impact.

- Hydrate and supplement: Start an iron-rich diet or supplement regimen at least a week before your scheduled donation to ensure your hemoglobin levels are high enough to give.