Ever watch a six-year-old try to figure out what comes after thirteen? It’s a struggle. They usually start counting from one, their little fingers tapping the air, because they haven't quite mastered the mental map of how numbers actually live in space. This is where the number path to 20 comes in. It’s not just a strip of paper with some digits on it. Honestly, it’s a cognitive bridge.

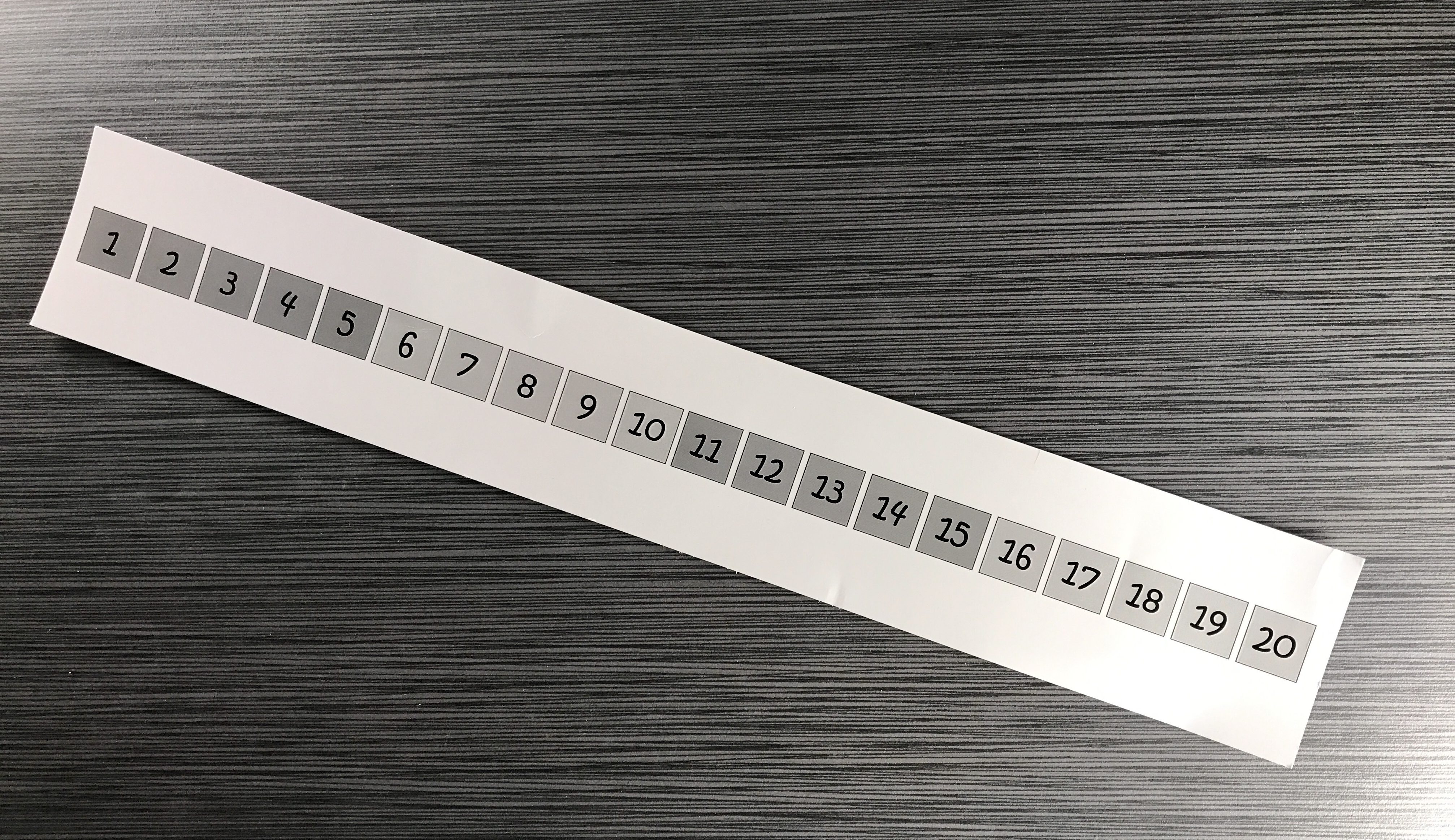

Most of us grew up with number lines. You know the ones—a long thin line with tiny hash marks and numbers sitting underneath. But for a kid whose brain is still figuring out that "7" represents seven physical objects, a number line is actually pretty confusing. The numbers are just points. There’s no "body" to them. A number path changes that by putting each number inside its own box. It makes the number a thing you can see, touch, and jump on.

Why a Number Path to 20 Beats the Traditional Number Line Every Time

If you look at the research from folks like Dr. Douglas Clements and Julie Sarama—they’re basically the gurus of early childhood math—they point out that young kids perceive numbers as "units." When a child sees a number line, they often struggle because they don't know whether to count the marks or the spaces between them. It’s a classic "off-by-one" error waiting to happen.

👉 See also: Walk in shower pictures: What Most People Get Wrong About Modern Bathrooms

The number path to 20 solves this. Each number is nestled in a distinct square. 1 is a box. 2 is a box. There’s no ambiguity. When a student moves from 5 to 6, they aren't just sliding along a line; they are moving from one room to the next. This spatial awareness is the secret sauce for developing "number sense," which is a fancy way of saying a kid actually understands what they’re doing instead of just memorizing stuff.

I’ve seen classrooms where teachers use giant floor versions of these. Kids literally jump from box to box. You’d think it’s just play, but their brains are mapping the distance between 8 and 12. They feel the effort of the four jumps. That physical movement translates into a mental model that stays with them way longer than a worksheet ever could.

The Problem with the Teen Numbers

Let's talk about the "teen" numbers for a second. They are a linguistic nightmare for English speakers. Think about it. We say "fourteen" (four and ten), but then we have "eleven" and "twelve" which sound like nothing else. In languages like Chinese or Japanese, the names are more logical—basically "ten-one," "ten-two."

Because our language is messy, the number path to 20 acts as a visual stabilizer. It shows that 11 is just one step past 10. By the time a child reaches the end of the path at 20, they’ve visually processed the transition from the single digits to the teens twice.

- Visualizing the "Ten-Frame" influence: Many high-quality paths use color coding. They might make 1-5 one color and 6-10 another.

- Breaking the 10-barrier: Seeing the 10 and 11 side-by-side helps kids realize that 11 is "ten and one more."

- Counting on: Instead of restarting at 1, a child can put their finger on 8 and "count on" three more to hit 11.

If a child can't visualize where 17 is in relation to 20, they’re going to hit a wall when they get to double-digit addition. It's just a fact. The path provides that mental scaffolding.

Common Misconceptions About Math Tools

People often think these tools are "crutches." I’ve heard parents say, "I don't want my kid relying on a chart; they should know it in their head." That’s kinda like saying a carpenter shouldn't use a level because they should just "know" if a floor is flat.

The goal of the number path to 20 isn't to be used forever. It’s to build the image inside the head. Eventually, the kid doesn't need the paper because they can "see" the boxes in their mind's eye. If you take the tool away too early, you aren't making them smarter; you're just making them guess. And guessing is the death of math confidence.

Another mistake? Using a path that’s too busy. If the path has cartoons, bright distracting borders, or weird fonts, the brain spends more energy processing the "art" than the math. Clean, high-contrast paths are the gold standard for a reason.

How to Use the Path at Home or in Class

You don't need a PhD to help a kid with this. Just get a path—or draw one—and play games. Simple stuff.

📖 Related: Old Navy Black Friday Ads: What the Typical Shopper Gets Wrong About the Savings

- The "Hidden Number" Game: Cover a number with a penny. Ask what's under there. How do they know? Do they count from one, or do they look at the neighbors?

- Race to 20: Roll a die. Move that many spaces. It’s basically Chutes and Ladders without the frustration.

- The "One More, One Less" Challenge: Point to 14. What's one more? What's one less? This is the foundation for addition and subtraction.

Specific evidence from the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics (NCTM) suggests that "subitizing"—the ability to recognize a group of objects without counting them—is reinforced when kids see numbers grouped in these path formats. When they see the 5-box and the 10-box as landmarks, they stop seeing a blur of numbers and start seeing a system.

Actionable Steps for Better Math Fluency

If you’re looking to actually implement this, stop overthinking it. Start with a physical model.

First, ensure the path you're using starts at 1, not 0. While 0 is mathematically vital later on, for a child learning to count objects, starting at 1 matches their physical reality.

Second, encourage "finger tracking." Have the child touch the box as they say the number. This multi-sensory approach (see it, say it, touch it) is what makes the neural connections stick.

Third, move to "counting on" as soon as they’re comfortable. If they are at 7 and need to add 4, don't let them start over at 1. Point at 7. Say "seven." Then hop: "eight, nine, ten, eleven." This is a massive leap in mathematical maturity.

Finally, keep the sessions short. Five minutes of focused work on a number path to 20 is worth an hour of frustrated staring at a textbook. Math shouldn't feel like a punishment; it should feel like solving a puzzle where you finally have the right pieces.

Once the child is cruising through the path to 20 without hesitation, you can introduce a 1-100 chart. But don't rush it. Mastery of the first 20 numbers is the bedrock. If that foundation is shaky, the whole house will eventually come down. Build it right the first time with a solid visual path.