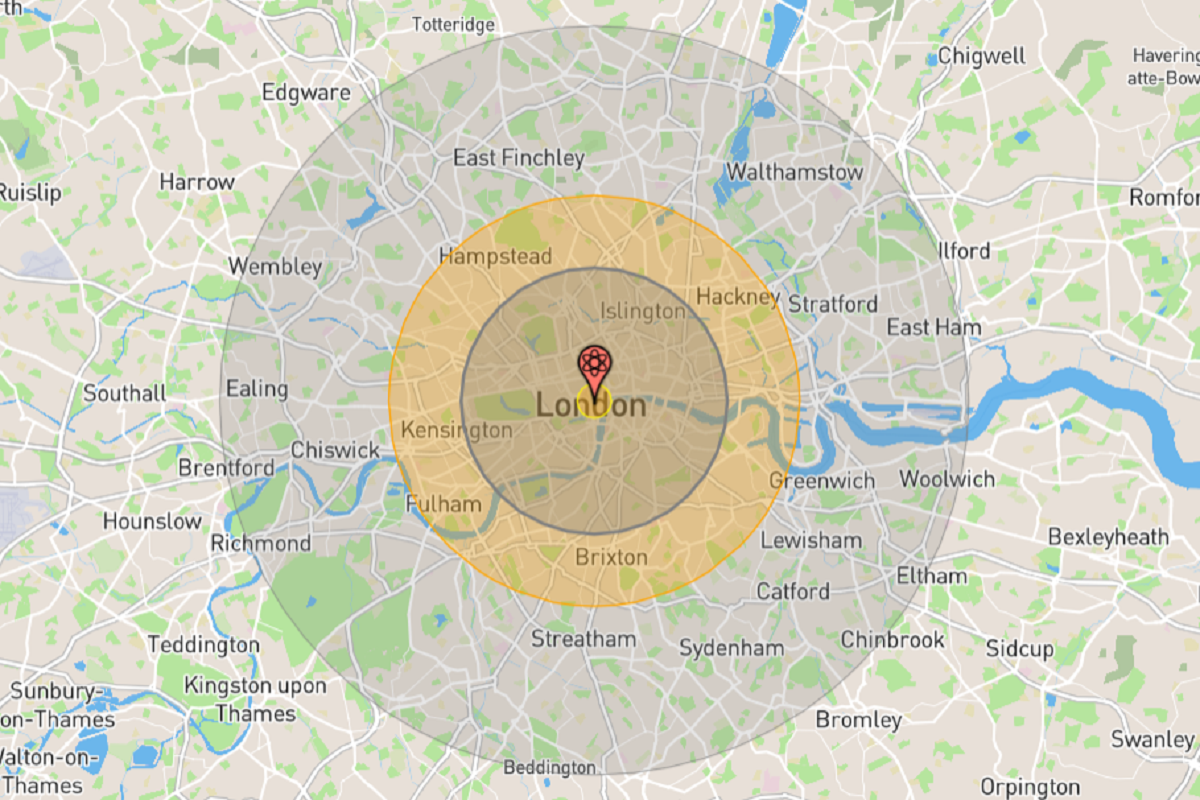

You’ve probably seen it. A bright red circle centered right over your house, or maybe your office downtown, bleeding out into shades of orange and yellow. It’s a weirdly addictive, deeply unsettling experience. Using a nuclear bomb map maker isn’t exactly a fun Saturday afternoon activity, but millions of people do it every year.

The most famous version of this is NUKEMAP. It was created by Alex Wellerstein, a historian of science at the Stevens Institute of Technology. He didn’t build it to be a "doom scrolling" tool. Honestly, he built it because humans are terrible at visualizing scale. When someone says "a 15-kiloton bomb," our brains sort of short-circuit. Is that a big firecracker or the end of the world? A digital map makes it real. It turns an abstract military statistic into a "what if my commute suddenly became a radioactive crater" scenario.

✨ Don't miss: Final Cut Pro Cost Explained: What You Actually Pay in 2026

How the Nuclear Bomb Map Maker Actually Works

The math behind these maps isn't just some random "guess-timation" pulled out of a hat. It’s based on decades of declassified data, much of it originating from the 1962 book The Effects of Nuclear Weapons by Samuel Glasstone and Philip J. Dolan. That book is basically the bible for anyone trying to calculate how a blast wave travels.

When you select a weapon—say, the "Little Boy" dropped on Hiroshima or the massive Soviet Tsar Bomba—the nuclear bomb map maker runs calculations for four primary effects. First, there’s the thermal radiation. This is the heat. It travels at the speed of light and causes third-degree burns far beyond the actual explosion. Then you’ve got the pressure wave. This is what knocks buildings down. It’s measured in "pounds per square inch" (psi).

Most people don't realize that the height of the burst matters more than the size of the bomb in many cases.

If a bomb explodes on the ground, it kicks up a ton of dirt. That dirt becomes radioactive and falls back down as fallout. If it explodes high in the air (an airburst), the blast wave is actually more destructive over a wider area because the pressure reflects off the ground and joins up with the incoming wave. But there's much less fallout. It’s these kinds of grim nuances that a tool like NUKEMAP lets you toggle with a single click.

The Psychological Pull of the Blast Zone

Why do we do this to ourselves? There’s a certain "morbid curiosity," sure. But researchers suggest it’s also about control. We live in a world where geopolitical tensions fluctuate. Seeing the visual boundaries of a "100% lethality" zone versus a "shattered windows" zone gives the brain a way to categorize the unthinkable.

Wellerstein has noted in various interviews that usage of his nuclear bomb map maker spikes whenever there’s a global crisis. When news cycles get dark, the servers for these maps start to sweat. It's a way for the average person to verify the threats they hear about on the news. Instead of relying on a talking head to tell them the world is ending, they can see for themselves exactly where the line of survival is drawn.

It’s also about debunking myths. A common misconception is that a single nuclear weapon would instantly vaporize an entire country. These maps show that while the destruction is horrific, it is geographically finite. You can be ten miles away from a small blast and survive, provided you aren't downwind of the fallout. That realization is both comforting and terrifying in its own right.

Technical Limitations and the "Science" of the Simulation

We have to be careful not to treat a nuclear bomb map maker as a perfect crystal ball. Reality is messy. The terrain matters. If you drop a bomb in a valley, the hills might shield the areas on the other side from the initial heat flash. If you’re in a city with skyscrapers, those buildings create "shadows" but also become deadly projectiles of glass and steel.

Most online maps use a "flat earth" model for the initial blast. They assume the ground is a smooth, featureless plane.

Wind is the biggest wildcard. Fallout patterns look like long, stretched-out cigars on the map, but in real life, wind changes at different altitudes. The "fallout" you see on your screen is a best-guess based on prevailing winds, not a guarantee.

👉 See also: How Do Search Engines Work: What Most People Get Wrong About the Algorithm

- Thermal Radiation: The flash that causes fires and skin burns.

- Overpressure: The physical "push" that collapses structures.

- Ionizing Radiation: The immediate burst of gamma rays and neutrons.

- Residual Fallout: The dust that drifts for miles, potentially for days.

Wellerstein's tool isn't the only one out there, though it’s the most refined. There are others like Outrider, which focuses more on the human cost and uses more stylized visuals. These tools serve as a bridge between cold, hard physics and the very human fear of extinction.

The Evolution of Public Perception

In the 1950s, the government gave out "slide rules" and paper maps for this. You’d have a little plastic wheel you’d turn to see if your fallout shelter was deep enough. Moving that logic to a browser-based nuclear bomb map maker has changed the "vibe" of nuclear education. It’s gone from a civic duty to a viral phenomenon.

Some critics argue these tools desensitize us. They turn mass tragedy into a "sandbox" game where you can swap out cities like you’re playing SimCity. But the counter-argument is stronger: by making the effects visible, we stop treating these weapons as "magic" and start treating them as physical realities that require diplomatic solutions.

Actionable Steps for Using Map Simulators Responsibly

If you’re going to use a nuclear bomb map maker, don’t just click "Detonate" and walk away. Use it to understand the actual mechanics of safety and civil defense.

Toggle the Airburst vs. Surface Burst. Notice how the fallout disappears during an airburst but the "heavy blast damage" circle gets significantly wider. This explains why military targets are treated differently than civilian ones in strategic planning.

Check the Wind Settings. Don't just use the default. Look up the actual wind direction in your area today. It’s a sobering reminder that a "safe" distance is entirely dependent on the weather.

Compare Weapon Yields. Look at the difference between a "Suitcase Bomb" (0.1 kilotons) and a modern ICBM warhead (300–800 kilotons). The scale difference is astronomical. It helps you realize that "nuclear" isn't just one single size.

Read the Descriptions. Most people ignore the sidebar text. It explains what "5 psi" actually means—it means your house is gone and the lungs of anyone inside are likely to be damaged.

Ultimately, these maps are educational tools. They are meant to strip away the Hollywood flash and show the raw, ugly physics of the Cold War's most dangerous legacy. By visualizing the "unthinkable," we might be more inclined to ensure it stays that way.