Let’s be honest. Nobody actually wants to think about a mushroom cloud blooming on the horizon. But humans are curious creatures, and in a world that feels increasingly unstable, people are flocking to tools like NUKEMAP to see exactly how their neighborhood would fare. Understanding a nuclear explosion radius map isn't just about doom-scrolling or morbid curiosity. It's about physics, thermal radiation, and the terrifyingly precise way energy displaces matter.

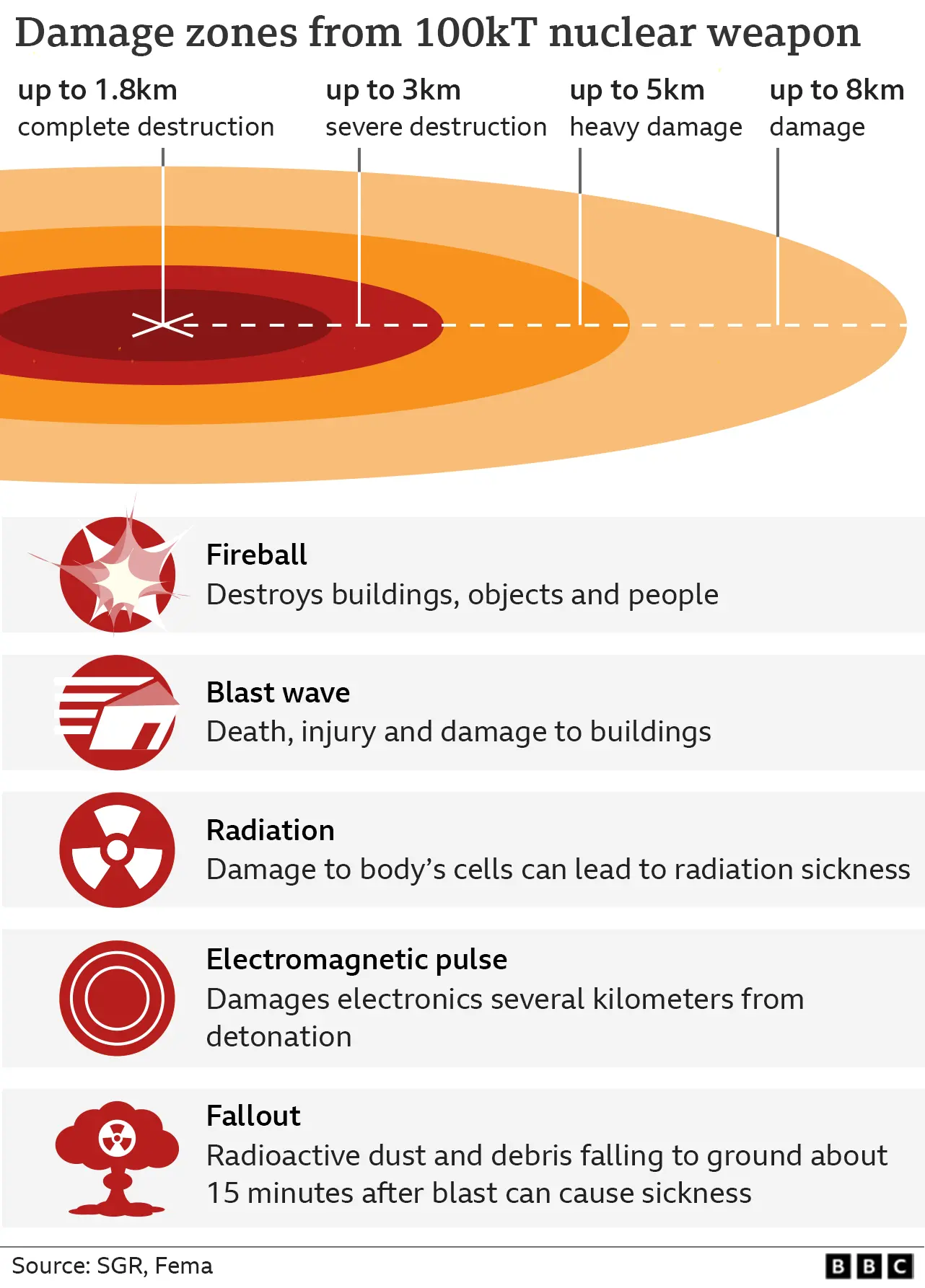

Most people imagine a nuclear blast as a simple circle of fire. You're either in it or you're out. That’s wrong. It’s actually a series of overlapping rings, each with its own specific brand of destruction. A 100-kiloton warhead—which is a fairly standard size for a modern reentry vehicle—doesn't just "blow up" a city. It dissolves the center, crushes the inner suburbs, and creates a massive, lethal heat wave that stretches for miles.

Why the Map Isn't Just One Big Circle

When you look at a nuclear explosion radius map, you’re looking at a cross-section of energy. The first thing that happens isn't the bang. It's the light. About 35% of the energy from a nuclear explosion is released as thermal radiation. This light travels at the speed of light, hitting you before you even hear the blast. If you’re within the "Thermal Radiation" radius, anything flammable—curtains, dry leaves, your clothes—ignites instantly.

Alex Wellerstein, a historian of science at the Stevens Institute of Technology, created the most famous version of these maps. He did it because he realized people have no sense of scale. They either think a nuke destroys the whole world or that it’s just a big conventional bomb. It’s neither. It’s a localized catastrophe with very specific mathematical boundaries.

👉 See also: How to Add More Than One Audio on Canva Without Losing Your Mind

The Fireball and the Pressure Wave

The center of the map is the fireball. For a 100-kiloton blast, this is surprisingly small—maybe only a few hundred yards across. But inside that tiny circle, the temperature is hotter than the surface of the sun. Everything is vaporized. Not burned. Not melted. Literally turned into a gas.

But the real killer on any nuclear explosion radius map is the blast overpressure. This is the "heavy air" that gets pushed out by the explosion. We measure this in pounds per square inch (psi).

- 5 psi: This is the threshold where most residential buildings collapse.

- 20 psi: Heavily built concrete structures are destroyed or severely damaged.

If you’re sitting in a suburban house and the map says you’re in the 5-psi zone, the house is going to pancake. The wind speeds here would be around 160 mph. Think of the worst hurricane you've ever seen, then imagine it hitting in half a second.

The Invisible Threat: Radiation and Fallout

Radiation is where the map gets messy. You have two types. Initial radiation happens in the first minute. It’s a massive burst of neutrons and gamma rays. On a nuclear explosion radius map, this circle is usually smaller than the thermal radiation circle. Basically, if you’re close enough to get a lethal dose of initial radiation, you’re probably already being hit by the heat or the blast wave.

Then there’s the fallout.

Fallout doesn't stay in a neat circle. It follows the wind. If a bomb hits New York and the wind is blowing east, Long Island is in trouble, but New Jersey might be totally fine. This is why a static nuclear explosion radius map can be misleading. You have to account for the "cigar-shaped" plume of radioactive dust that drifts downwind. This dust is made of pulverized dirt and debris that was sucked up into the mushroom cloud, became highly radioactive, and then started "falling out" of the sky.

Height Matters More Than You Think

Here’s something most people get wrong: the "Airburst" vs. the "Surface Burst."

If a nuclear weapon is detonated on the ground, it creates a lot of fallout because it sucks up tons of dirt. However, the blast radius is actually smaller because the ground absorbs a lot of the energy.

If you detonate it a few thousand feet in the air—an airburst—the blast wave reflects off the ground and combines with itself. This is called the "Mach Stem" effect. It significantly extends the nuclear explosion radius map for structural damage. This is how the bombs were used over Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The goal was to maximize the "crushing" power over a wider area.

Modern Warheads vs. Historical Reality

The Little Boy bomb dropped on Hiroshima was about 15 kilotons. Today, a single Russian RS-28 Sarmat (Satan II) can carry multiple warheads, each many times more powerful than that. When you plug these numbers into a nuclear explosion radius map, the scale is dizzying.

A 15-kiloton blast has a "third-degree burn" radius of about 1.1 miles.

A 1-megaton blast (1,000 kilotons) has a "third-degree burn" radius of roughly 6.8 miles.

The area of a circle increases with the square of the radius. So, while the bomb is 66 times more powerful, the area of destruction is vastly larger. You're talking about entire metropolitan regions being engulfed in a firestorm.

The Misconception of "Total Annihilation"

People often assume a nuclear war means everyone dies instantly. It doesn't. Even on a nuclear explosion radius map of a major city, there are "survivable" zones. The problem is what comes after.

If you are in the "Light Blast Damage" zone (around 1 psi), your windows will shatter. In a city like London or DC, that means millions of people with glass lacerations. The medical infrastructure would vanish. This is the nuance that a map can't show—the "social collapse" radius.

We also have to talk about the "Flash Blindness." If you are 50 miles away and look at the explosion, you can be temporarily or permanently blinded. The map of "potential eye damage" is much larger than the map of physical destruction.

Real-World Tools and Modeling

If you want to see this for yourself, the NUKEMAP by Alex Wellerstein is the gold standard. It uses the DHRA (Defense Nuclear Agency Retaliation Analysis) equations. These aren't just guesses; they are based on the thousands of atmospheric tests conducted during the Cold War.

Another tool is MISSILEMAP, which shows how these weapons actually get to their targets. When you combine a nuclear explosion radius map with a delivery system map, you realize how little time there is to react. An ICBM from across the ocean arrives in about 30 minutes. A sub-launched missile from off the coast? Less than 10.

Actionable Steps for Understanding Your Risk

Knowing the physics is one thing; knowing what to do is another. If you find yourself looking at a nuclear explosion radius map because of a genuine threat, here is the expert-level reality:

- Find the "Shadow": If you are outside the immediate fireball but within the thermal range, putting a solid object between you and the flash is the difference between life and death. This is called "Flash-to-Bang" time.

- The 24-Hour Rule: Fallout is most dangerous in the first 24 to 48 hours. If you are in the downwind plume, stay inside. Ideally, go to a basement or the center of a large concrete building.

- Don't Look at the Light: This sounds simple, but the human instinct is to look at the bright flash. If you see a sudden, inexplicable increase in light, drop to the ground and cover your head.

- Check the Wind: Understand the prevailing winds in your area. This will tell you which way the fallout plume is likely to travel on your local nuclear explosion radius map.

The map is a tool for visualization, but it’s also a reminder of the sheer scale of energy involved in splitting the atom. It’s not a movie. It’s a very specific, very fast, and very hot set of mathematical equations playing out in real space.