If you’ve spent any time on the internet lately, you’ve probably seen one. A nuclear bomb radius map is that terrifying tool where you type in your zip code, pick a warhead, and watch a series of colored circles swallow your city. It’s morbidly fascinating. You see the "fireball" ring, the "radiation" ring, and the "pressure" ring. But honestly? Most of these maps, while scientifically grounded in physics, don't tell the whole story of what actually happens when a weapon of mass destruction meets a complex modern landscape.

People use them to calculate survival. They want to know if they’re in the "instant vapor" zone or the "shattered windows" zone. It's a natural human reaction to a threat that feels too big to grasp. But the physics of a blast aren't as neat as a perfect circle on a 2D map.

What These Maps Are Actually Showing You

The most famous version of this tech is NUKEMAP, created by Alex Wellerstein, a historian of science at the Stevens Institute of Technology. It’s become the gold standard for educators and, let’s be real, doom-scrollers everywhere. It uses the DHHS (Defense High-Frequency SAR) and other declassified blast effects data to project damage.

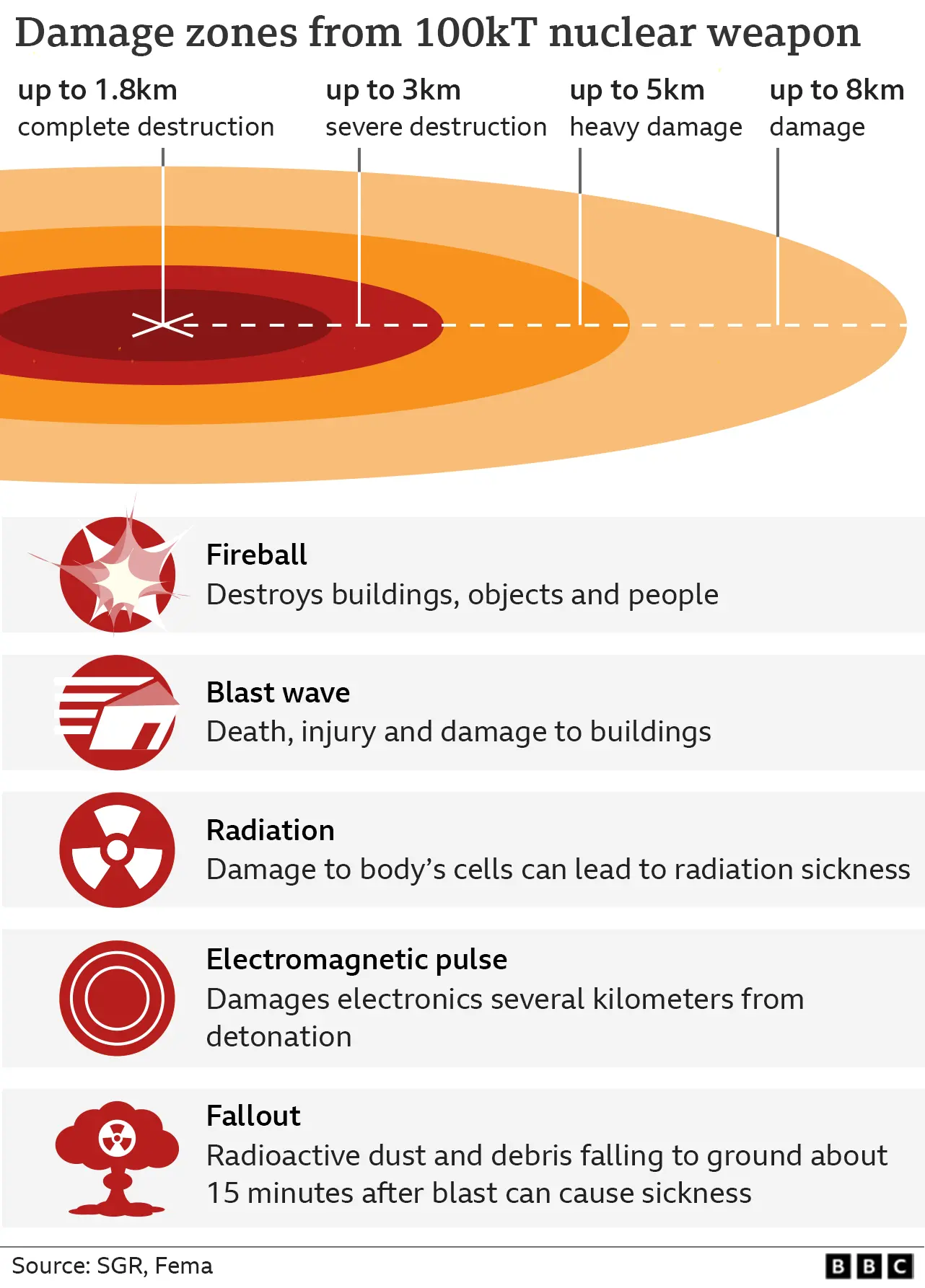

When you look at a nuclear bomb radius map, you’re seeing four or five distinct zones. First, there’s the fireball. If you’re in it, you aren't even a memory anymore. It's a thermal pulse so hot it literally turns solid matter into plasma. Then comes the heavy pressure zone—the "5 psi" or "20 psi" rings. This is where the air itself becomes a hammer, knocking down reinforced concrete buildings like they're made of playing cards.

But here’s the thing: those circles are based on flat terrain. If you live in a valley or behind a massive mountain range, the "shadow" of that geography can actually deflect part of the thermal pulse or the shockwave. Conversely, the "canyon effect" in a city like New York or Chicago can funnel a blast wave down a street, actually increasing its pressure in certain spots. A circle on a map doesn't show you that. It’s a simplification of a chaotic, fluid-dynamic event.

The Problem With "Average" Yields

Most people default to the Hiroshima "Little Boy" (15 kilotons) or a modern Topol-M (800 kilotons) when playing with these maps. There’s a massive gap there. A 15-kiloton bomb creates a fireball with a radius of about 180 meters. An 800-kiloton bomb? That fireball is closer to 0.8 kilometers wide.

The thermal radiation—the stuff that causes third-degree burns—reaches way further than the blast wave. On a clear day, a 1-megaton blast can cause burns up to 11 kilometers away. But if it’s a foggy day or there’s heavy smoke? That radius shrinks significantly because the water droplets in the air scatter the thermal energy.

- The Thermal Pulse: This is the light. It travels at the speed of light. You feel the heat before you hear the bang.

- The Blast Wave: This is the air. It travels roughly at the speed of sound. This is what breaks the glass and collapses the roofs.

- Initial Radiation: This happens in the first minute. It’s nasty, but the blast usually kills you before the radiation does if you're close enough to get a lethal dose.

- Fallout: This is the wild card.

Why Fallout is the Hardest Part to Map

You’ll notice on a nuclear bomb radius map that fallout usually looks like a long, distorted cigar shape stretching away from the center. This is based on prevailing winds. But wind isn't a straight line. It changes with altitude.

The radioactive debris—mostly pulverized dirt and building materials sucked up into the mushroom cloud—is heavy. It falls back down. If the bomb is an "airburst" (detonated high in the sky to maximize the blast footprint), there’s actually very little local fallout because the fireball doesn't touch the ground. It doesn't "suck up" the dirt. But if it’s a "ground burst," you have a massive radioactive problem that can travel hundreds of miles.

Wellerstein’s NUKEMAP and the older FEMA models show this, but they can't account for a sudden rainstorm. If it rains while a fallout cloud is overhead, you get "rainout," which dumps the radiation in a concentrated "hot spot" rather than letting it spread out thin.

The Survival Gap: 5 PSI and the Human Factor

Most experts, including those from the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, point to the 5 psi (pounds per square inch) overpressure ring as the "threshold of survival" for people who aren't in bunkers. At 5 psi, most residential houses collapse. If you're inside, you’re likely crushed. If you’re outside, the wind—which is moving at roughly 160 mph at this pressure—will throw you.

However, if you're in a basement or a reinforced parking garage, your survival odds in that 5 psi zone skyrocket. This is why the nuclear bomb radius map can be a bit misleading. It makes everything inside the circle look like a "dead zone," but history (like the survivors in Hiroshima who were in reinforced basements) shows that shielding and distance are a sliding scale, not a binary.

How to Use These Tools Without Spiraling

It’s easy to get overwhelmed. You see the "100% lethality" zone and think there’s no point in even learning about it. But understanding the nuclear bomb radius map is actually a key part of civil defense. It tells you where the most "winnable" zones are.

For instance, the "Light Damage" zone is where most injuries occur—not from the blast itself, but from flying glass. If you’re on the edge of a map's radius, simply knowing to move away from windows when you see a flash (which travels faster than the sound) can be the difference between being blinded/lacerated and walking away clean.

The maps are tools for visualization. They help policy makers understand the scale of a 100-kiloton vs. a 5-megaton weapon. They show that a "limited" exchange isn't really limited when you factor in the healthcare collapse that follows the destruction of a city center.

Practical Realities Most People Ignore

We focus on the explosion. We don't focus on the "darkness" that follows.

If a bomb hits a city, the nuclear bomb radius map won't show you the EMP (Electromagnetic Pulse). It won't show you that every cell tower is down, every car with an electronic ignition is a brick, and the power grid is fried for a thousand miles. The map shows the physical reach of the weapon, but the "functional reach" of a nuclear strike is essentially global.

Also, consider the "medical shadow." If a city has ten major hospitals and eight of them are within the 5 psi ring, the remaining two hospitals are now responsible for 500,000 burn victims. The map shows a circle of damage; it doesn't show the secondary circle of systemic collapse.

Actionable Steps for Better Understanding

If you're going to use a nuclear bomb radius map for research or personal curiosity, do it with a bit of scientific rigor.

- Check the "Airburst" vs. "Surface Burst" settings. An airburst maximizes the area of a "moderate damage" zone (5 psi), which is what a military would use to destroy a city. A surface burst is for destroying underground silos and creates way more radioactive fallout.

- Look at the "Thermal Radiation" ring. This is almost always the largest circle. This is where you need to worry about fires. If you live in a wooded area or a place with lots of wooden houses, the "radius" of the firestorm might actually be larger than the blast radius itself.

- Learn the "Flash-to-Bang" method. Light travels at 300,000 kilometers per second. Sound travels at about 0.34 kilometers per second. If you see a flash that looks like a second sun, you have a very short window—maybe seconds—to get away from windows and drop to the floor before the shockwave hits.

- Acknowledge the limitations. These maps don't account for your house being behind a big hill or the fact that you have a concrete basement. They are "average" projections.

The value of a nuclear bomb radius map isn't just in the fear it produces. It's in the data. It’s in the realization that these weapons are so powerful that the only real "defense" is making sure they are never used in the first place. Use the maps to educate yourself on the physics, but remember that the real-world impact involves variables that a browser-based tool can't fully simulate.

Moving Forward with the Data

Don't just stare at the circles. If you're looking at a nuclear bomb radius map for emergency preparedness, identify the "moderate damage" zones around your area. Those are the places where "Duck and Cover" actually works. In the "Total Destruction" zone, there's nothing to prepare for. But in the outer 60% of the blast's reach, simple actions—knowing which way the wind blows (for fallout) and having a plan to shelter in place—actually save lives.

The map is a starting point, not the final word. It shows the potential, but your geography, your building’s construction, and your reaction time are what define the reality.

Next Steps for Deepening Your Knowledge

📖 Related: Valcat B2B SaaS Go-To-Market Automation: Why Most SaaS Teams Are Doing It Wrong

To get a truly accurate picture of your local risk, you should look at the National Planning Scenario 1, which is the federal government’s playbook for a nuclear event. It details the "dangerous fallout zone" (DFZ) which is much more nuanced than the simple circles you see on a web map. You can also research "nuclear thermal shielding" to understand how even a simple layer of white clothing can drastically change the effect of the thermal pulse at the edge of the radius.