If you’ve spent more than a week living near Lake Erie, you know the drill. The sky turns a bruised shade of purple, the wind starts whipping the oak trees, and you frantically refresh your phone. You’re looking for that green and yellow blob to tell you if you have time to finish mowing the lawn. But here’s the thing: Northeast Ohio doppler radar isn't just one giant eye in the sky. It’s a patchy, complex network of government beams and private sensors that sometimes struggle to keep up with our "lake effect" chaos.

Weather in Cleveland, Akron, and Youngstown is notoriously fickle. One minute it’s sunny; the next, you’re in a whiteout.

Most people assume the radar they see on Channel 3 or Channel 8 is a real-time video feed of the rain. It isn't. Not even close. What you're actually looking at is a reconstructed map of microwave pulses bouncing off raindrops and snowflakes. In our neck of the woods, those pulses have to deal with some pretty weird physics.

The Big Dog in Wilmington and the Cleveland Gap

Most of the heavy lifting for our local forecasting comes from the National Weather Service (NWS). Specifically, the KCLE WSR-88D radar stationed at Cleveland Hopkins International Airport. This is the gold standard. It’s a massive, high-powered dish tucked inside a fiberglass "soccer ball" (the radome).

But it has a weakness. Curvature.

The Earth isn't flat, despite what some corners of the internet might tell you. Because the radar beam travels in a straight line, it gets higher and higher above the ground the further it travels from the source. By the time the Cleveland beam reaches places like Mansfield or the fringes of Youngstown, it might be looking several thousand feet above the actual clouds where the snow is forming. This is why you sometimes see "ghost rain" on your app—stuff that’s up high but evaporates before it hits your driveway—or why a massive snow squall seems to appear out of nowhere.

💡 You might also like: Why the iPhone 7 Red iPhone 7 Special Edition Still Hits Different Today

It didn't appear out of nowhere. The radar was just looking over the top of it.

Why Lake Effect Snow Breaks the System

Lake effect snow is the ultimate villain for Northeast Ohio doppler radar. Why? Because it’s "shallow." Unlike a massive summer thunderstorm that reaches 40,000 feet into the atmosphere, lake effect clouds are often low-hanging. They hug the ground.

If you're in Ashtabula or Erie, Pennsylvania, the Cleveland radar beam is basically shooting right over the top of the snow clouds. This creates a "blind spot" that meteorologists have to fill in using other tools like satellite imagery or surface observations. Honestly, it’s a bit of a guessing game sometimes. To compensate, the NWS often relies on the KBUF radar out of Buffalo or the KPBZ station near Pittsburgh to get a "cross-eyed" view of what’s happening in the snow belt.

The Dual-Polarization Revolution

About a decade ago, the technology got a massive upgrade called Dual-Pol. Before this, the radar only sent out horizontal pulses. It could tell how wide a raindrop was, but not how tall.

Now, it sends both horizontal and vertical pulses.

📖 Related: Lateral Area Formula Cylinder: Why You’re Probably Overcomplicating It

This matters because it helps the computers distinguish between a big, fat raindrop and a jagged snowflake. It even helps identify non-weather "clutter." In Northeast Ohio, we get a lot of biological interference. Basically, bugs and birds. During migration seasons, the radar picks up massive swarms of mayflies over Lake Erie or flocks of birds taking off at dawn. Dual-Pol technology lets the meteorologists at the Cleveland NWS office filter out the insects so you don't think a storm is brewing when it’s actually just a billion midges.

High-Resolution vs. Broad-Brush Radar

You might notice that the radar on a local news site looks way sharper than the basic NWS feed. Stations like WJW (Fox 8) or WKYC often talk about their "proprietary" or "live" radar.

Here is a secret: they aren't usually operating their own multi-million dollar WSR-88D stations. Instead, they often subscribe to high-speed data feeds or use smaller, "gap-filler" radars. These are X-band radars. They have a shorter range but much higher resolution. They’re great for spotting a rotation in a small cell over Strongsville that the larger government radar might have smoothed over.

But even these have a catch. X-band radar signals get "attenuated." If there’s a massive downpour right next to the radar, the signal gets absorbed and can't see what's happening behind the storm. It’s like trying to see through a thick curtain with a flashlight.

How to Actually Read the Map Like a Pro

Stop just looking at the colors. Most people see red and panic.

👉 See also: Why the Pen and Paper Emoji is Actually the Most Important Tool in Your Digital Toolbox

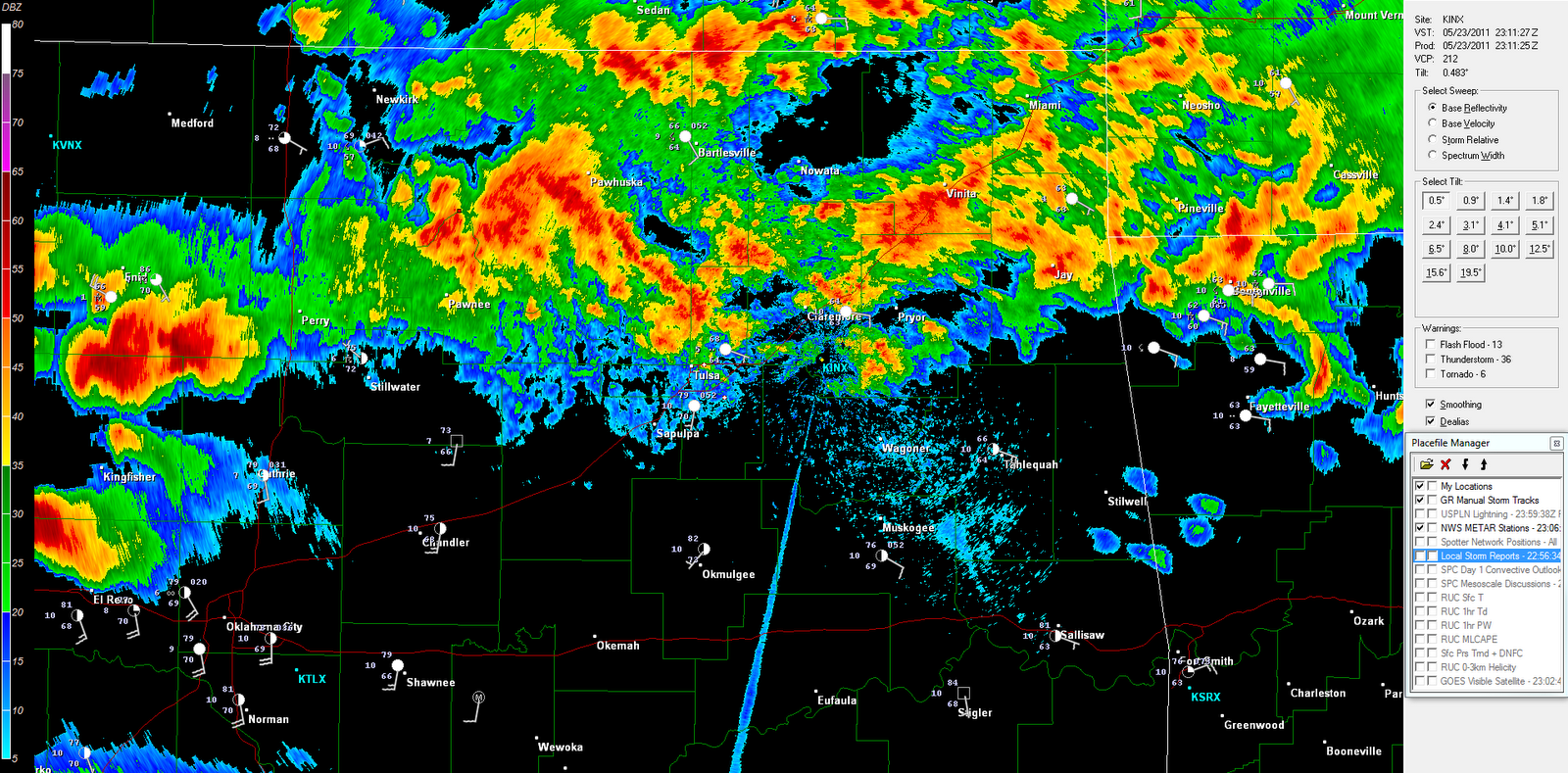

In Northeast Ohio, look for the "velocity" view if your app allows it. While "reflectivity" shows you where the rain is, velocity shows you which way the wind is blowing relative to the radar. This is how you spot a tornado. You’re looking for a "couplet"—a spot where bright green (wind moving toward the radar) is right next to bright red (wind moving away). In a place like the Cuyahoga Valley, where terrain can slightly influence low-level wind, seeing that rotation early is the only way to get a ten-minute head start.

Also, pay attention to the time stamp. Most free apps have a 5-to-10 minute delay. If a storm is moving at 60 mph, that "red blob" is already 10 miles ahead of where your phone says it is.

The Human Element: SKYWARN Spotters

Despite all the billion-dollar tech, the most reliable "radar" in Northeast Ohio is often a person standing in a field with a radio. The SKYWARN program is massive here. These are volunteers trained by the NWS to report what’s actually happening on the ground.

When the radar says "hail possible," it’s the spotter in Medina or Chardon who confirms it’s actually nickel-sized. This human feedback loop is piped directly into the NWS workstation, which is why your phone suddenly chirps with a warning even if the radar looks relatively calm.

Actionable Steps for Your Next Storm

Don't rely on one source. That is the biggest mistake people make. If you want to stay ahead of the weather in the 216 or 330, you need a layered approach.

- Get a "Pro" App: Use something like RadarScope or RadarOmega. These apps give you raw data from the KCLE station without the "smoothing" that makes free apps look pretty but less accurate. You can see the individual pixels of a storm.

- Check the Base Reflectivity: Always look at the lowest "tilt" (0.5 degrees). This is the closest view to the ground and the most relevant to your actual backyard.

- Watch the Loop, Don't Just Look at the Still: In Northeast Ohio, storms often "pulse." They grow and die in cycles of 20 minutes. If you see a cell growing in intensity over the last three frames of a loop, expect it to be worse when it hits you.

- Identify Your "Radar Home": If you live in Youngstown, you are better off looking at the Pittsburgh (KPBZ) radar. If you're in Sandusky, look at the Detroit or Cleveland feeds. Knowing which beam is closest to your house removes the "altitude error" that causes missed forecasts.

The tech is incredible, but it's limited by the curve of the Earth and the height of the clouds. Use it as a guide, not a gospel. When the sky turns that weird shade of green over Lake Erie, trust your eyes as much as your screen.