You’ve probably messed around with those little neodymium office magnets or maybe the clunky ceramic ones on your fridge. It feels like magic. One side clicks together so fast it might pinch your skin, while the other side pushes away with this weird, invisible resistance that feels like trying to squish two pieces of rubber together. That push and pull is the fundamental reality of the north pole and south pole in magnet physics. It’s not just a school project topic. It’s the reason your car starts, your phone vibrates, and the Earth doesn’t get fried by solar radiation.

Magnets are weird.

Think about it. You have a solid object that can exert force on another object without even touching it. At the heart of this "spooky action" are the two poles. Every magnet, no matter its shape or size, has them. If you take a bar magnet and snap it right down the middle, you don’t get a "north" piece and a "south" piece. You just get two smaller magnets, each with its own brand-new north and south pole. This happens because magnetism isn't just on the surface; it's a property of the atoms themselves.

What Makes a Pole a Pole?

Basically, magnetism comes down to electrons. In most materials, electrons spin in random directions, and their tiny magnetic fields just cancel each other out. It's a wash. But in ferromagnetic materials like iron, cobalt, or nickel, these spins can be nudged to line up. When enough of these "atomic magnets" point the same way, you get a macroscopic magnetic field.

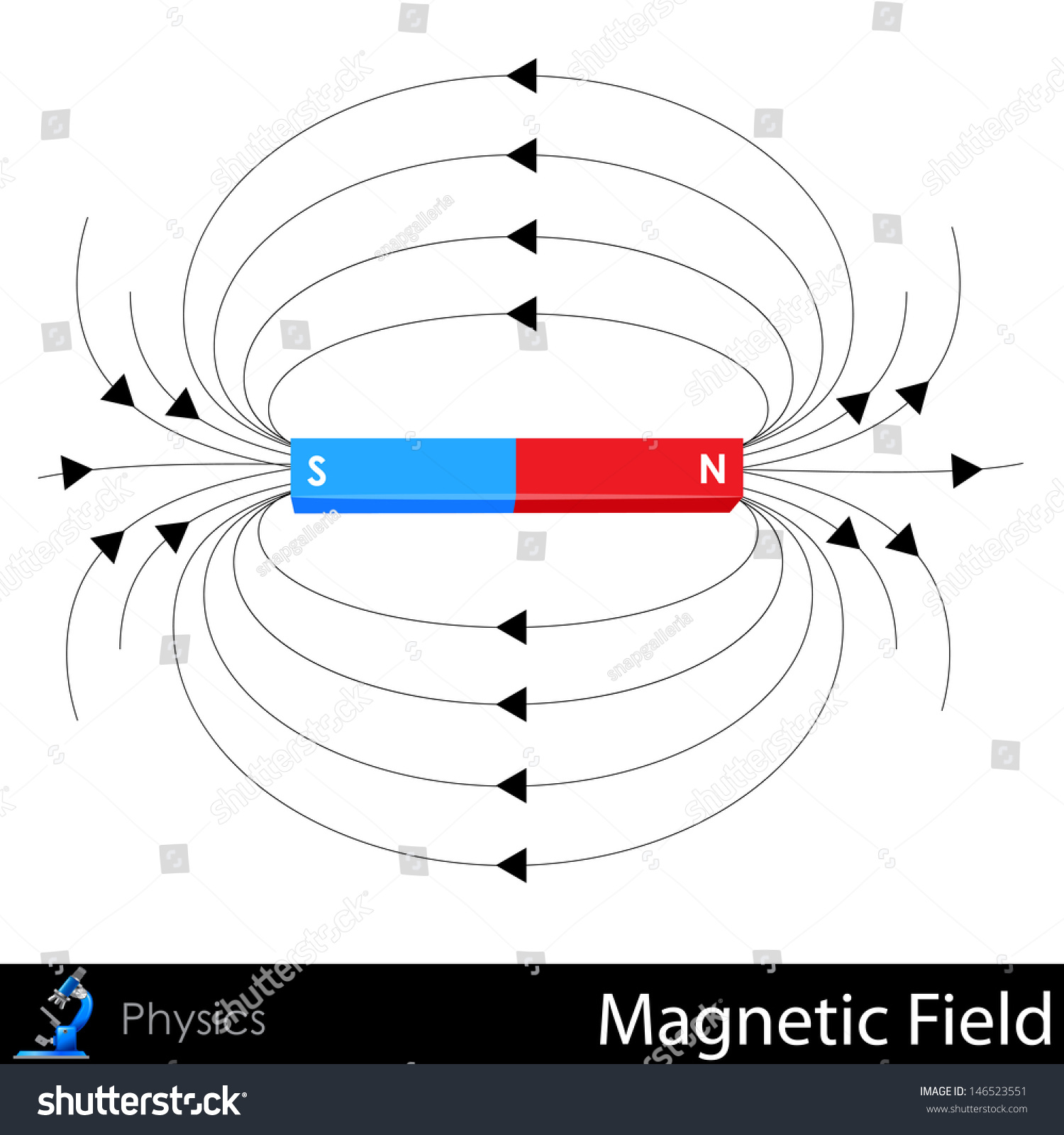

The north pole and south pole in magnet dynamics are defined by the direction of this field. By convention, we say the magnetic field lines flow out of the North Pole and loop back around into the South Pole. It's a continuous loop. Inside the magnet, the lines actually travel from south to north to complete the circuit.

Why do we call them "North" and "South" anyway? It’s kind of a historical accident based on how we use them for navigation. A "North-seeking" pole is the end of a magnet that points toward the Earth's geographic North Pole. Because opposites attract, this actually means the Earth’s geographic North is secretly a magnetic South Pole. I know, it’s a bit of a brain-melter, but that's the literal physics of it.

The Law of Attraction (and Repulsion)

It’s the first thing we learn: Likes repel, opposites attract. If you bring a North pole near another North pole, the magnetic field lines are essentially clashing. They refuse to merge. They bend away from each other, creating that "invisible wall" feeling you get when you try to force two magnets together.

But bring a north pole and south pole in magnet pairs together? The field lines from the North pole find a "sink" in the South pole. They bridge the gap, creating a tension that pulls the two objects together. It’s a bit like a rubber band stretching between them.

Real-World Magnetic Domains

If you’ve ever dropped a permanent magnet and noticed it got weaker, or if you’ve heated one up over a stove, you’ve witnessed the destruction of "domains." Inside an iron bar, there are these little microscopic neighborhoods called domains. In a non-magnetized piece of iron, the domains are all arguing—pointing in different directions. When you "magnetize" it, you’re basically a drill sergeant forcing all those neighborhoods to face the same way.

Heat jiggles the atoms so much that they lose that alignment. Dropping it does the same through mechanical shock. This is why "permanent" magnets aren't always permanent. Scientists like those at the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory spend their entire careers looking at how these domains behave under extreme pressure or cold.

The Earth as a Giant Bar Magnet

We can’t talk about the north pole and south pole in magnet science without looking at the ground beneath our feet. The Earth is basically a giant, slightly messy bar magnet. This is caused by the movement of molten iron and nickel in the outer core. This "geodynamo" creates a massive magnetic field called the magnetosphere.

- The Geographic North: This is the "top" of the world on a map. It’s fixed.

- The Magnetic North: This is where your compass actually points.

- The Drift: Magnetic North isn't a fixed spot. It moves. Currently, it’s hauling tail from the Canadian Arctic toward Siberia at about 34 miles per year.

This movement is a big deal for navigation systems. Every few years, airports have to repaint the numbers on their runways because those numbers are based on compass headings, and the Earth's "magnet poles" have shifted enough to change the reading.

Breaking the Monopole Myth

One of the biggest "Holy Grails" in physics is the search for a magnetic monopole. Since every north pole and south pole in magnet always comes as a pair, scientists wonder if it's possible to have just a North or just a South.

Paul Dirac, a legendary physicist, predicted they should exist back in 1931. If we found one, it would rewrite most of our electromagnetism textbooks. So far? Nothing. We've seen "quasiparticles" that act like monopoles in specialized crystals called "spin ice," but a true, isolated magnetic charge remains unseen in the wild. Every time you cut a magnet, nature "heals" the break by creating two new poles instantly. It’s a fundamental rule of the universe: magnetism is dipolar.

How Modern Tech Uses the Poles

Honestly, we’d be living in the dark ages without the interplay between the north pole and south pole in magnet setups.

- Electric Motors: These work by constantly switching the polarity of electromagnets. By flipping the North and South poles rapidly, you can use the "repulsion" to push a rotor around and around. That's what powers everything from your Tesla to the fan in your laptop.

- Data Storage: Your old-school hard drives store data by flipping the polarity of tiny magnetic grains on a spinning platter. A "North" might be a 1, and a "South" might be a 0.

- Maglev Trains: These use massive magnets to hover the train. By using like-poles to repel (North against North), the train stays suspended in the air, eliminating friction.

- MRI Machines: These use insanely strong magnetic fields—thousands of times stronger than a fridge magnet—to align the protons in your body. By pulsing these fields, doctors can see inside you without cutting you open.

Practical Experiments You Can Actually Do

If you want to see the north pole and south pole in magnet fields for yourself, don't just take my word for it.

👉 See also: Will Meta Split in 2025: What Most People Get Wrong

Grab a clear plastic container and fill it with baby oil and some iron filings (you can get these by dragging a magnet through some sand, usually). When you place a magnet near the container, the filings will align themselves along the field lines. You'll see the "hairy" looking lines arching from one pole to the other. It’s the closest you’ll get to seeing the invisible skeleton of the universe.

Another cool trick is the "floating magnet." Take two ring magnets and slide them onto a pencil. If you put the North poles facing each other, the top magnet will just hang there in mid-air. It's a simple demonstration, but it's the exact same physics used in multi-billion dollar Maglev projects in Japan and China.

Common Misconceptions to Toss Out

People often think that the North Pole of a magnet is "stronger" than the South Pole. It's not. They are perfectly symmetrical in terms of flux. If one side seems stronger, it's usually just because of the shape of the magnet or a flaw in how it was manufactured.

Another one? That all metals are magnetic. Most aren't. Aluminum, copper, and gold don't care about your magnets. You can hold a powerhouse neodymium magnet up to a gold bar and... nothing. This is actually a common way to test if "gold" jewelry is fake; if it sticks to a magnet, it’s probably got an iron or nickel core.

Getting the Most Out of Your Magnets

If you're working with magnets for a DIY project or just curious, remember that distance is the enemy. Magnetic strength drops off incredibly fast. It follows the inverse square law—sorta. Basically, if you double the distance between a north pole and south pole in magnet interaction, the force doesn't just get cut in half; it drops to a fraction of what it was.

Also, watch out for "Neodymium" magnets. They are brittle. If you let a North and South pole snap together from a distance, they can shatter like glass. I've seen people get nasty blood blisters because they underestimated how fast those poles want to meet each other.

To keep your magnets "healthy," store them in pairs with their poles attracting (North to South). This creates a closed loop for the magnetic field and helps maintain the alignment of those internal domains over the long haul. Using "keepers"—small blocks of iron—across the poles is even better. It gives the magnetic flux a solid path to follow, which prevents the magnet from "leaking" its strength into the surrounding air.

To dive deeper into the world of magnetism, you should start by mapping the magnetic fields in your own home. Use a basic compass to see how electronics—like your microwave or computer speakers—distort the Earth's natural field. You'll quickly realize that we are living in a dense forest of North and South poles, all pushing and pulling in a silent, invisible dance.

If you're looking for your next project, try building a simple "homopolar motor" with just a battery, a copper wire, and a neodymium magnet. It’s the simplest way to see how a magnetic pole can turn electrical energy into physical motion in real-time. Just be careful with those strong magnets around your credit cards and old-school watches—they’ll wipe those strips and mess up the gears faster than you can say "ferromagnetism."