Talking about the North Korea famine usually feels like trying to describe a room by looking through a keyhole. You get bits of data, a few harrowing grainy photos, and plenty of rumors, but the full picture stays blurry. Honestly, it’s frustrating. For decades, the world has watched the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK) swing between "just getting by" and "on the brink of catastrophe." People often ask if it's as bad as the 1990s. The short answer? No, not yet, but the situation is undeniably precarious.

When you look at the North Korea famine history, specifically the "Arduous March" of the mid-90s, you’re looking at a death toll that likely reached into the millions. It was a perfect storm of Soviet subsidies vanishing, horrific floods, and a government that basically froze in place. Today, the landscape is different. We have markets. We have better (though still old) farming techniques. But we also have a global pandemic that led the regime to seal its borders tighter than they've ever been in modern history.

The Arduous March and why it still haunts the North

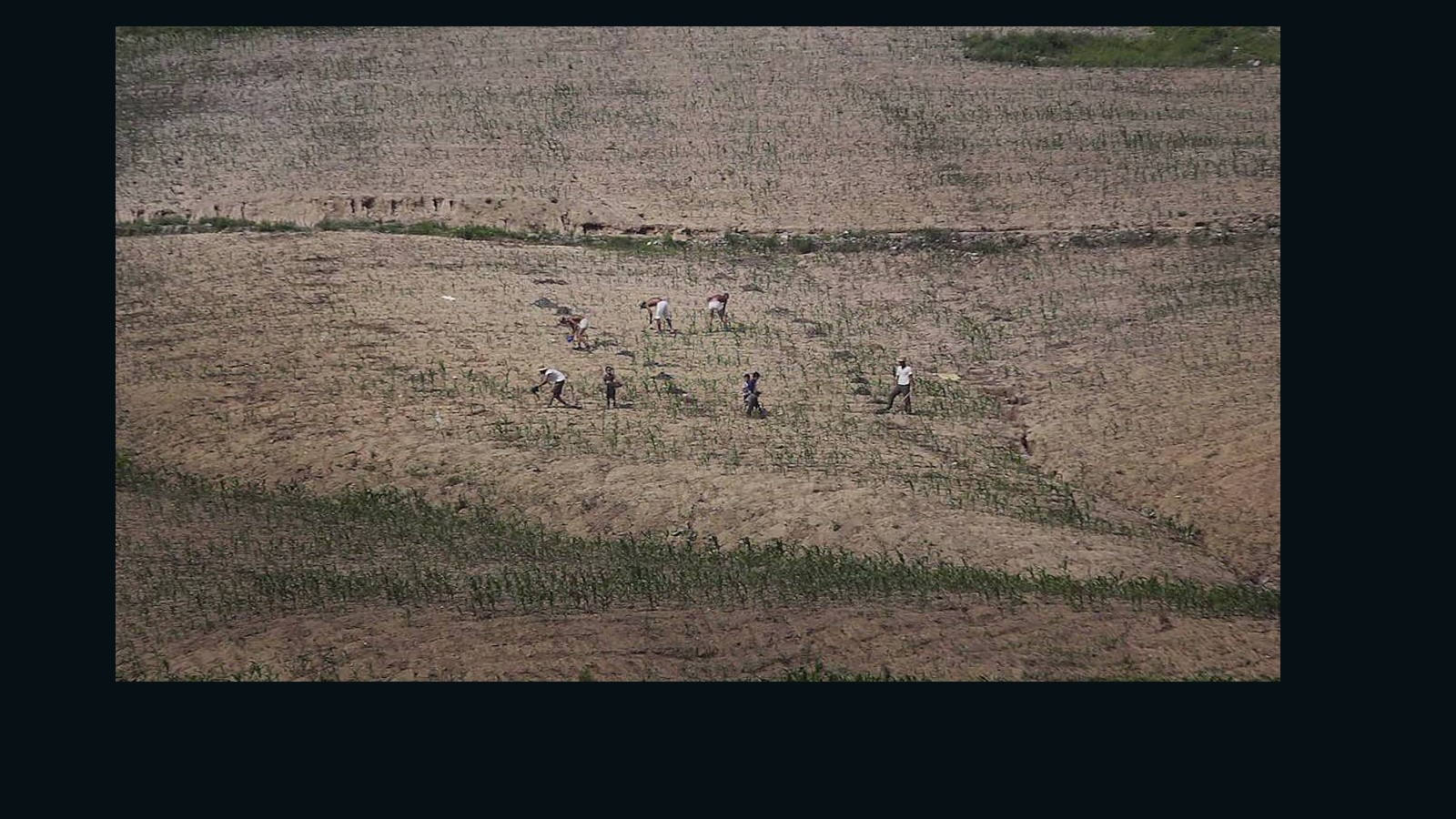

To understand why the North Korea famine is such a constant threat, you have to look at the geography. This isn't a land of rolling wheat fields. It’s a mountainous, rugged place where only about 17% of the land is actually good for farming. Back in the 1990s, when the food supply collapsed, the Public Distribution System (PDS)—the government’s way of feeding everyone—just stopped working. People died in their homes waiting for rations that never came.

Witness accounts from that time are brutal. Dr. Norbert Vollertsen, a German doctor who worked there, described seeing children with skin stretched over bone and bellies swollen from eating grass and bark. It wasn't just a lack of food; it was a total breakdown of society.

Nowadays, North Koreans have developed a "market mentality." They have jangmadang, or private markets. This is basically how the country survived the last twenty years. If the government can't provide corn, people trade whatever they can—clothes, scrap metal, handmade tools—to buy it from someone who smuggled it in from China.

🔗 Read more: Lake Nyos Cameroon 1986: What Really Happened During the Silent Killer’s Release

Why the food crisis spiked after 2020

Everything changed with COVID-19. Kim Jong Un didn't just close the borders; he locked them down with a "shoot-to-kill" policy for anyone crossing from China. For a country that relies on Chinese fertilizer, fuel, and spare parts for tractors, this was a self-inflicted wound.

Human Rights Watch and various UN agencies have been ringing the alarm bells. By 2022 and 2023, reports started leaking out about entire families dying of starvation in their homes. This is significant. It’s a return to the 90s-style tragedy where isolation, rather than just bad weather, becomes the primary killer.

The fertilizer problem

You can’t grow food without nutrients. North Korea’s soil is exhausted. Decades of intensive farming without proper crop rotation have left the dirt "dead." They need chemical fertilizers. When the border closed, the price of fertilizer skyrocketed. Farmers tried using "night soil" (human waste), but without the chemical supplements, the yields of rice and maize dropped significantly.

The climate factor

The weather hasn't been helpful. The 2024 growing season faced erratic rainfall. North Korea is caught in a cycle of "drought followed by deluge." When the rain finally comes, it doesn't just water the plants; it washes away the topsoil because there aren't enough trees to hold the earth in place—most were cut down for firewood during the last North Korea famine.

💡 You might also like: Why Fox Has a Problem: The Identity Crisis at the Top of Cable News

The internal politics of hunger

It’s easy to blame nature, but politics plays a huge role here. The "Military First" policy (Songun) means that soldiers and the elite in Pyongyang get the lion's share of whatever food is available. The people in the northern provinces, like Ryanggang or North Hamgyong, are often left to fend for themselves.

Economists like Marcus Noland from the Peterson Institute for International Economics have pointed out that food insecurity in the DPRK is often a distribution problem, not just a production one. The government spends billions on its missile program and nuclear development while refusing to import enough grain to fill the "food gap." Experts estimate that gap is usually around 800,000 to 1 million tons of grain per year.

The role of China and Russia

North Korea isn't totally alone, though. China remains their biggest lifeline. Beijing doesn't want a total collapse—that would mean millions of refugees flooding over the border and potentially a US-aligned South Korea taking over the entire peninsula. So, they send "aid." It’s often unpublicized. Trucks and trains carry grain and oil across the Yalu River bridge.

Recently, Russia has entered the mix in a big way. Since the war in Ukraine started, North Korea has reportedly been trading artillery shells and missiles for Russian food and technology. This "ammunition-for-bread" swap has likely prevented a full-scale North Korea famine in the last 18 months. It’s a grim trade, but for a regime that prioritizes survival above all else, it works.

📖 Related: The CIA Stars on the Wall: What the Memorial Really Represents

Signs to watch for: How we know it's getting worse

Since we can't just fly into Pyongyang and do a census, we have to look for "proxy indicators."

- Rice Prices: If the price of rice in the markets spikes 50% in a week, something is very wrong.

- The "Corn-Rice Ratio": In North Korea, rice is the "prestige" food. When people can't afford rice, they switch to corn. If they can't afford corn, they switch to "alternative foods" like roots and grass.

- Defector Height: This is a long-term study, but North Korean defectors are consistently several inches shorter than their South Korean counterparts. It’s a literal physical manifestation of chronic malnutrition over generations.

- Satellite Imagery: We can see the "greenness" of the crops from space. Analysts use this to predict the harvest months before it happens.

Is there a solution?

Honestly? It’s complicated. Providing aid is a moral imperative, but it’s also a logistical nightmare. The DPRK government often refuses to let aid workers monitor where the food goes. They want the bags of flour delivered to the port, and then they want the workers to leave. This leads to "diversion," where the food ends up in the hands of the military or is sold on the black market by corrupt officials.

NGOs like Liberty in North Korea (LiNK) and various humanitarian groups argue that we should keep trying, regardless of the regime's behavior. They focus on the human cost. But as long as the border remains tightly controlled and the government prioritizes weapons over wheat, the specter of a North Korea famine will continue to hang over the population.

Actionable insights for the concerned

If you’re looking to understand or help with the crisis, here are the most effective ways to stay informed and involved:

- Follow Reliable Monitoring Sources: Don't just trust every headline. Look at 38 North, Daily NK, and the NK News food price trackers. These outlets use networks of informants inside the country to get real-time data on what a kilogram of rice actually costs in Sinuiju or Hyesan.

- Support Grassroots Organizations: Organizations that focus on helping refugees (like LiNK) are often more effective than large-scale government aid because they work directly with the people who have escaped and can provide the most accurate intelligence on the ground.

- Distinguish Between "Shortage" and "Famine": A shortage means people are hungry; a famine means people are dying en masse. Currently, North Korea is in a state of chronic, severe food insecurity with localized pockets of starvation. Understanding this nuance helps in advocating for the right kind of intervention.

- Pressure for "Humanitarian Exemptions": Even when sanctions are tight, there are legal pathways for food and medicine. Supporting policies that ensure these exemptions are easy to navigate helps ensure that political pressure on the regime doesn't accidentally become a death sentence for the civilian population.

The situation remains fluid. One bad harvest or one more year of total border isolation could tip the scales from "struggling" to "catastrophic." Keeping the world's eyes on the most vulnerable provinces is the only way to ensure history doesn't repeat itself.