You’re sitting in a terminal at JFK or maybe Heathrow, looking out at a gray, swirling sky, and you pull up your favorite weather app. You see those familiar green and yellow blobs of rain moving across the coast. But then you scroll out. You swipe your thumb across the screen, moving toward the vast, empty blue of the North Atlantic.

The colors vanish.

It’s just blank. Most people assume we have a giant, "God’s eye" view of everything happening between New York and Ireland, but the reality of North Atlantic ocean weather radar is way more complicated—and a bit more primitive—than you’d think. We have satellites, sure. We have models. But actual ground-based radar? That thing has a shorter leash than a nervous chihuahua.

The 250-Mile Wall

Here’s the thing about radar: it’s "line of sight."

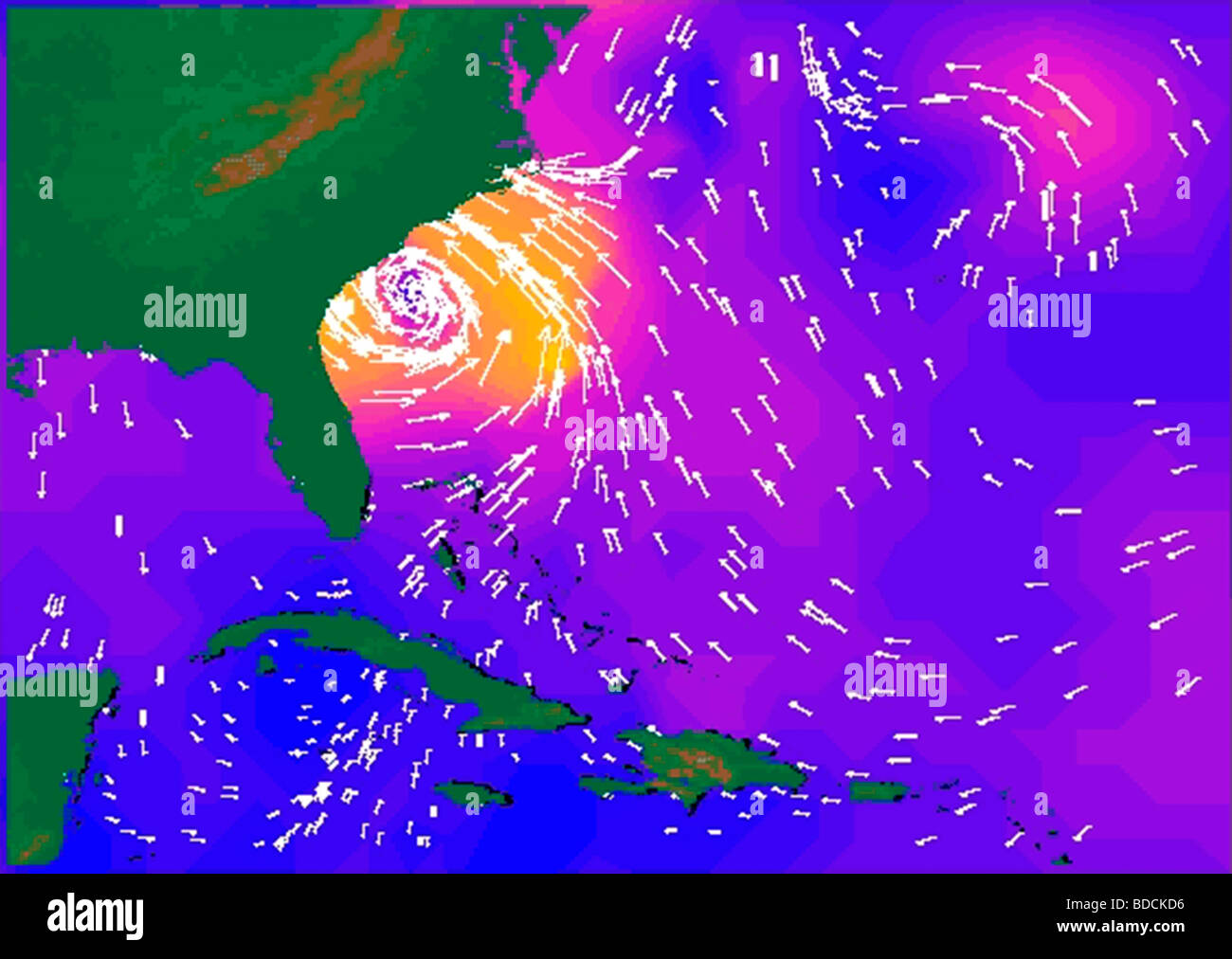

If you stand on the coast of Newfoundland and point a standard S-band or C-band radar dish at the horizon, the earth eventually curves away. The beam keeps going straight, shooting off into space while the ocean drops beneath it. This means that for most of the North Atlantic, traditional radar is effectively blind. You’ve basically got a 200 to 250-mile "bubble" around the coastlines. Once a storm moves past that imaginary line, it enters a bit of a data black hole.

We take for granted that we know exactly where a hurricane or a "bomb cyclone" is at every second. In the middle of the ocean, we’re actually relying on a patchwork of different technologies to fill the gaps that radar leaves behind. It’s not one single screen. It’s a messy, high-stakes puzzle.

Why We Can't Just Put Radars on Buoys

I get asked this a lot. If we need radar in the middle of the Atlantic, why don't we just bolt some dishes onto those yellow research buoys?

The ocean is violent.

🔗 Read more: The MOAB Explained: What Most People Get Wrong About the Mother of All Bombs

Think about the sheer mechanical nightmare of keeping a massive, rotating radar dish—which needs a stable platform and a massive power source—functional on a floating piece of metal in 40-foot swells. Salt spray corrodes electronics faster than you can imagine. Plus, radar needs to be perfectly level to be accurate. If the "floor" is pitching 20 degrees to the left every five seconds, your data is garbage.

Instead, we use things like the Global Drifter Program, managed by NOAA. These aren't radars. They are small, basketball-sized spheres that float with the currents. They measure atmospheric pressure and sea-surface temperature. It’s "point data." It’s like trying to understand a whole movie by looking at three random pixels on the screen. It helps, but it isn't the high-resolution "radar" view we crave.

Spaceborne Radar: The Real MVP

Since we can't easily put radars on the water, we put them above it.

This is where the Global Precipitation Measurement (GPM) Core Observatory comes in. This is a joint venture between NASA and JAXA (the Japanese space agency). Unlike your local TV news radar, GPM carries a Dual-frequency Precipitation Radar (DPR). It actually "looks" down through the clouds to see the 3D structure of a storm over the North Atlantic.

It's incredible tech. But there is a catch.

Satellites like GPM are in Low Earth Orbit (LEO). They aren't staring at one spot 24/7. They’re orbiting the planet at 17,000 miles per hour. They fly over a specific patch of the North Atlantic, take a "snapshot," and then they're gone. If a massive storm is brewing at 2:00 PM and the satellite isn't scheduled to pass until 4:00 PM, we’re back to using infrared imagery and water vapor sensors from geostationary satellites like GOES-East.

GOES-East is that "big picture" view you see on the evening news. It sits 22,000 miles up. It stays in the same spot relative to Earth. The problem? It doesn't use radar. It uses cameras and sensors to see clouds. It can tell you where the clouds are, but it can't always tell you exactly how hard it's raining deep inside the heart of a storm system halfway to Iceland.

💡 You might also like: What Was Invented By Benjamin Franklin: The Truth About His Weirdest Gadgets

The Secret Role of Transatlantic Flights

Believe it or not, your summer vacation to Paris is actually helping us map the weather.

Because the North Atlantic is the busiest oceanic flight corridor in the world, aircraft act as moving weather stations. Through a system called AMDAR (Aircraft Meteorological Data Relay), commercial planes automatically transmit wind speed, temperature, and turbulence data back to ground stations.

When a pilot flies through the "North Atlantic Tracks," their onboard weather radar is scanning the sky. While that data isn't always integrated into a public-facing "radar map" for you to look at on your phone, it is vital for meteorologists at the National Hurricane Center or the UK Met Office. They use this "in-situ" data to verify if their computer models are actually right about that developing low-pressure system.

The "Bomb Cyclone" Problem

The North Atlantic is famous for "extra-tropical cyclogenesis." That’s the fancy term for when a storm's pressure drops so fast it basically becomes a winter hurricane. We call them bomb cyclones.

Without a continuous North Atlantic ocean weather radar network, predicting exactly where these bombs will "go off" is a nightmare. In 2022, a massive system developed off the US East Coast. The models were split. Some said it would track toward the Maritimes; others said it would veer toward the open sea.

Because we don't have a solid radar "tether" in the deep ocean, forecasters have to wait for the storm to get close enough to a coastal radar—like the ones in Cape Race, Newfoundland, or the Azores—to see the fine-scale structure. By then, it’s often too late for ships to change course.

How to Actually "See" the Weather Out There

If you are a sailor, a pilot, or just a weather nerd who wants to track things over the ocean, you have to stop looking for a "radar" and start looking for "reconstructed composites."

📖 Related: When were iPhones invented and why the answer is actually complicated

Websites like Windy.com or Ventusky are popular because they look like radar. But they aren't. They are visualizations of GFS (Global Forecast System) or ECMWF (European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts) models. They are "guessing" based on physics equations.

If you want the closest thing to real-time data, you look for ASCAT (Advanced Scatterometer) data. This is a satellite-based sensor that measures the "roughness" of the ocean surface to determine wind speed and direction. If the water is choppy, the wind is high. It’s a clever workaround for our lack of mid-ocean radar towers.

The Future: Drone Ships and Starlink

We’re getting better.

Companies like Saildrone are now deploying uncrewed surface vehicles that can stay at sea for a year. These drones carry a suite of sensors that can mimic some radar functions. And with the rise of Starlink and high-speed satellite internet, the cost of beaming high-bandwidth weather data from the middle of the ocean has plummeted.

We might eventually see a "virtual radar" network built out of thousands of autonomous sensors all talking to each other. But for now? We’re still playing a game of connect-the-dots.

Actionable Insights for Tracking Atlantic Weather

If you need to monitor weather over the North Atlantic for travel or work, stop relying on standard rain radar apps. They will lie to you by omission. Instead, use these specific tools:

- Check the NHC Marine Forecasts: The National Hurricane Center provides "High Seas Forecasts." These are text-based, but they are the most accurate summaries of what's happening in the radar-blind zones.

- Use Ocean Prediction Center (OPC) Surface Analyses: Look for "Surface Pressure" maps. In the North Atlantic, pressure tells a much bigger story than rain echoes. Closely packed "isobars" (lines on the map) mean dangerous winds.

- Monitor GOES-East Water Vapor Imagery: Instead of looking for rain, look for water vapor. This shows the "invisible" moisture in the atmosphere and can tell you where a storm is strengthening long before the clouds look scary on a standard satellite photo.

- Look at Buoy Observations via the NDBC: Visit the National Data Buoy Center website. If you see a buoy in the path of a storm reporting a "significant wave height" of 30 feet, you don't need a radar to tell you it's a mess out there.

The North Atlantic is a wild, unmapped frontier for traditional radar. Understanding that the "blank spots" on your app aren't empty—they're just unobserved—is the first step in staying safe on or over the water.

Next Steps:

If you're planning a crossing, start by overlaying ASCAT wind data with ECMWF pressure models to see the gap between "forecasted" and "observed" conditions. This discrepancy is usually where the biggest surprises happen. For those on land, following the Ocean Prediction Center on social media provides the most direct access to the expert "human" interpretation of these data gaps.