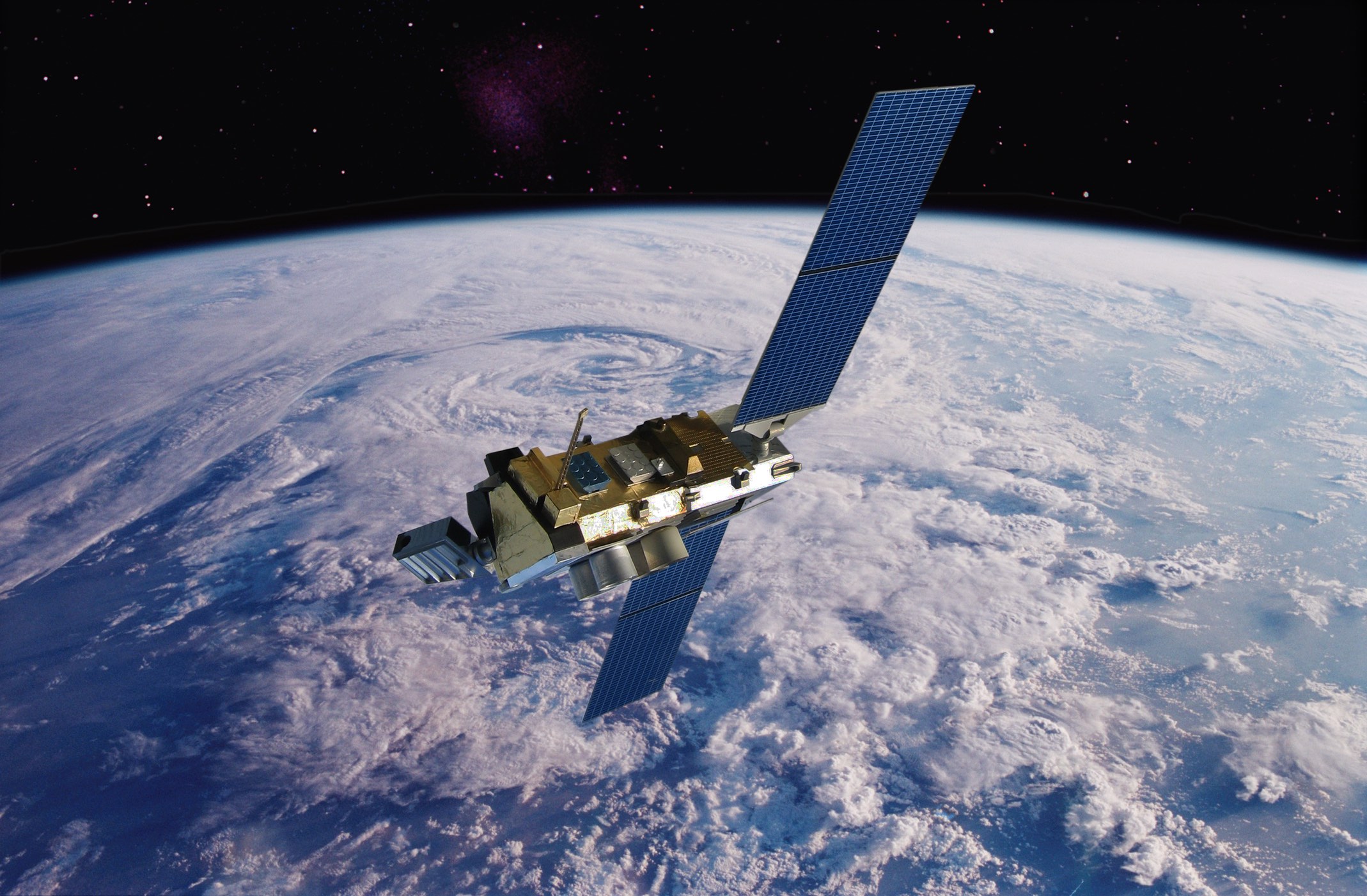

You probably don’t think about it when you check your phone for the afternoon high, but there is a massive, school-bus-sized piece of machinery hanging out 22,236 miles above the equator right now, staring directly at you. Honestly, it’s kind of wild. We take for granted that the "rain starting in 15 minutes" alert is actually accurate most of the time. That wasn't the case twenty years ago. The reason for this shift is almost entirely due to the evolution of the North American weather satellite network, specifically the GOES-R series.

It’s a high-stakes game. If these things fail, we’re essentially flying blind.

Back in the day, weather satellites were basically just flying cameras that took grainy black-and-white photos of clouds. You’d see a swirl and think, "Yeah, that's probably a hurricane." Today, the technology is so precise it can track the lightning inside a single storm cell in real-time. This isn't just about knowing if you need an umbrella; it's about the literal survival of coastal communities and the efficiency of the entire global supply chain.

The GOES Era: More Than Just "Weather"

When we talk about the primary North American weather satellite infrastructure, we are talking about the Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellite system, or GOES. This is a joint venture between NOAA (the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) and NASA. Currently, the stars of the show are GOES-East and GOES-West.

They stay fixed.

Unlike polar-orbiting satellites that zip around the Earth, geostationary ones match the Earth’s rotation perfectly. This means GOES-East (GOES-16) sits and stares at the Atlantic and Eastern U.S., while GOES-West (GOES-17/18) watches the Pacific and the West Coast.

The leap from the old "I-Series" to the "R-Series" was massive. Imagine going from a flip phone camera to a professional DSLR. The Advanced Baseline Imager (ABI) on the current satellites can scan the entire Western Hemisphere in just five minutes. If there’s a massive wildfire in California or a developing tornado in Oklahoma, it can zoom in and provide updates every 30 seconds.

Thirty seconds.

That speed is the difference between a siren going off in time or people being caught in their cars. Meteorologists use 16 different spectral bands on the ABI to see things the human eye can't, like water vapor in the upper atmosphere or the exact temperature of a cloud top. Higher cloud tops usually mean a more violent storm.

Why Lightning Mapping Changed Everything

One of the coolest—and most underrated—parts of the modern North American weather satellite is the Geostationary Lightning Mapper (GLM). Before this, we relied on ground-based sensors. Ground sensors are okay, but they often miss "in-cloud" lightning.

Why does that matter?

Because a sudden "spike" in in-cloud lightning is a huge red flag that a storm is about to turn severe or drop a tornado. The GLM sees these pulses from space continuously. It’s the first instrument of its kind in geostationary orbit. It detects the momentary changes in an optical scene, indicating a flash, even during the day when the sun is reflecting off the clouds.

The Polar Orbiters: The Unsung Heroes of the 7-Day Forecast

While GOES gets all the glory for real-time tracking, your 7-day forecast actually relies on a different kind of North American weather satellite. These are the JPSS (Joint Polar Satellite System) birds. They fly much lower—about 512 miles up—and they orbit from pole to pole.

As the Earth rotates under them, they "scan" the entire planet twice a day.

If you’ve ever wondered why your weather app can predict a cold front five days out, thank the JPSS. These satellites carry the Cross-track Infrared Sounder (CrIS) and the Advanced Technology Microwave Sounder (ATMS). They measure temperature and moisture throughout the entire atmosphere, not just the surface. This data is fed into massive supercomputers running the Global Forecast System (GFS) model.

Without this "vertical" data from polar orbiters, forecast accuracy would drop off a cliff after about 48 hours. It’s essentially the difference between a guess and a calculation.

Space Weather: The Threat Nobody Sees

There is another side to the North American weather satellite mission that sounds like science fiction: Space Weather.

💡 You might also like: Why the Bose x LISA Ultra Open Earbuds are Actually a Big Deal for Fashion

The sun isn't just a static ball of light; it’s a temperamental nuclear reactor. Occasionally, it spits out a Coronal Mass Ejection (CME). If a massive burst of solar plasma hits Earth, it can fry power grids, knock out GPS, and destroy communication satellites.

The GOES-R satellites carry sensors specifically designed to watch the sun. The Solar Ultraviolet Imager (SUVI) and the Extreme Ultraviolet and X-ray Irradiance Sensors (EXIS) monitor solar flares. By catching these events the second they happen, NOAA can give power companies and airlines a "heads up" to mitigate the damage. It’s a literal shield made of data.

The Challenges: Junk, Costs, and Physics

It isn't all perfect, though. Space is getting crowded.

The "Kessler Syndrome" is a real concern among satellite operators. This is the idea that one collision could create a cloud of debris that triggers a chain reaction, eventually making certain orbits unusable. While a North American weather satellite sits way out in geostationary orbit—which is less crowded than Low Earth Orbit—it’s not immune to the risks of space junk or solar degradation.

Then there's the cost.

Building and launching a single GOES satellite costs roughly $1 billion. That is a lot of taxpayer money. Critics often ask if we could do it cheaper with "smallsats" or private companies like SpaceX or Planet. While private industry is great for high-res imagery of your backyard, they don't yet have the specialized, highly calibrated instruments needed for climate-grade weather data.

🔗 Read more: Video of SpaceX Explosion: What Really Happened with the Recent Failures

Also, the physics of geostationary orbit are unforgiving. You can't just "fix" a satellite that's 22,000 miles away. If a sensor fails, that’s it. You’re looking at a billion-dollar brick. This is why these satellites are built with insane levels of redundancy.

How You Can Actually Use This Info

Most people just look at the little icon of a sun or a cloud on their phone. But if you want to be the "expert" in your friend group, you should go straight to the source.

NOAA offers public access to GOES-East and GOES-West imagery. If you’re planning a hike or a boat trip, don't just look at a forecast. Look at the water vapor imagery. If you see a dark "dry" slot moving toward you, it usually means high winds are coming. If you see "bubbling" cloud tops on the visible spectrum, a thunderstorm is firing up.

Basically, the data is there for everyone.

Next Steps for Better Personal Forecasting:

- Skip the middleman: Visit the NOAA GOES Image Viewer. It's free and updated in near real-time.

- Look for "GeoColor": This combines multiple bands to show you what the Earth looks like to the human eye, but it also highlights city lights at night and shows smoke from fires in distinct colors.

- Check the "Water Vapor" channel: This is the best way to see the "jet stream" and how weather systems are actually moving across North America. Clouds are just the symptoms; water vapor is the cause.

- Monitor the Space Weather Prediction Center: If you hear about an "Aurora" being visible further south than usual, check the SWPC site to see if a solar storm is hitting.

The North American weather satellite network is a silent guardian that we only notice when it's gone or when a major hurricane is bearing down. Understanding that it's a mix of geostationary "watchers" and polar-orbiting "calculators" helps make sense of why our forecasts have become so incredibly precise over the last decade. It's a massive feat of engineering that happens every single day, right over our heads, while we’re just wondering if we need a light jacket.