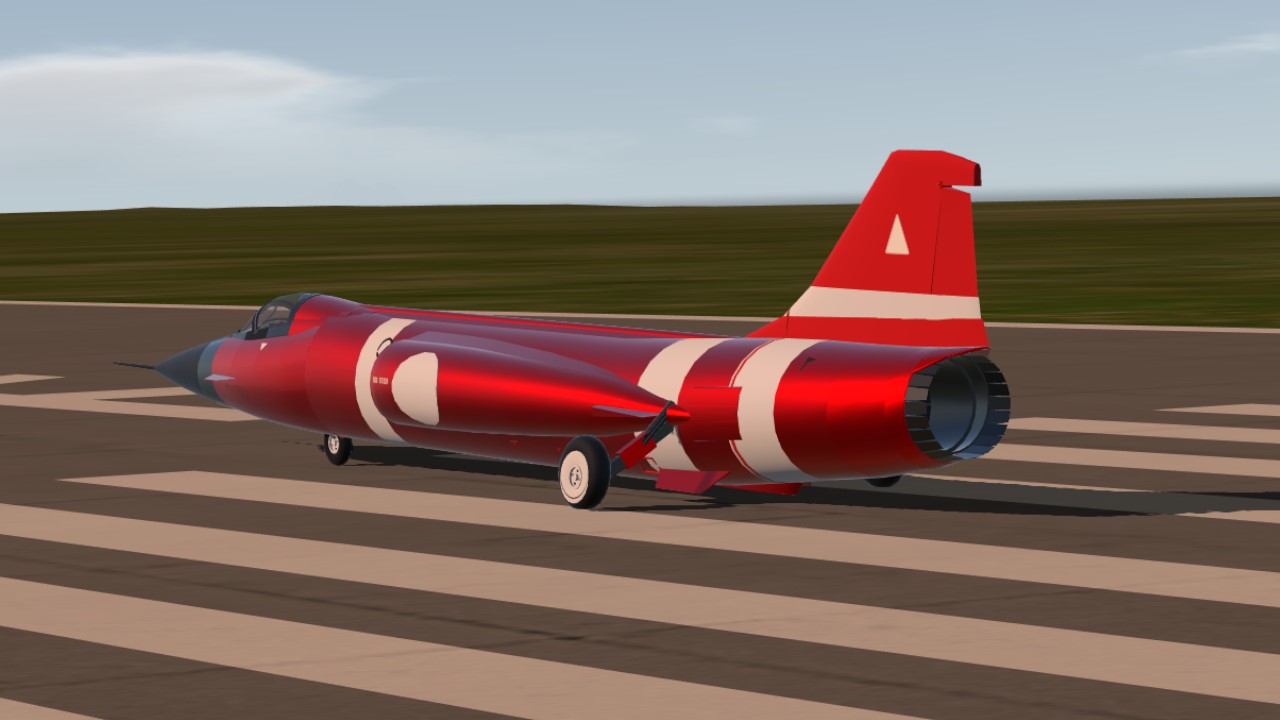

Speed is a drug. For Ed Shadle and Keith Zanghi, that addiction wasn't about a weekend at the drag strip or a fast lap in a Porsche. It was about 800 miles per hour. They wanted to reclaim the world land speed record for the United States, a title held by the British since 1983. To do it, they didn't go to a car manufacturer or a billionaire's tech lab. They went to a scrap yard and bought a 1950s fighter jet. Specifically, a Lockheed F-104A Starfighter.

The North American Eagle Project was never just a car. It was a 56-foot-long, fire-breathing experiment in physics. Think about that for a second. You take a plane designed to intercept Soviet bombers at twice the speed of sound, rip off the wings, and try to keep it glued to the desert floor. It sounds like madness because, honestly, it kind of was.

The Junk Yard Jet that Could

Most people assume land speed record attempts involve millions of dollars in corporate sponsorship from the jump. Not this one. The team started with a carcass. In 1998, Shadle and Zanghi found the remains of F-104A-10-LO, tail number 56-0763, sitting in a field in Maine. This particular airframe had a history; it was used as a chase plane for the X-15 program at Edwards Air Force Base. It had seen history, and the team decided it was going to make some more.

Building the North American Eagle Project was a masterclass in "making it work." The General Electric J79 turbojet engine was the heart of the beast. In its flight configuration, it produced about 15,000 pounds of thrust with the afterburner kicked in. Translating that power to a vehicle with wheels instead of wings is where the engineering nightmare begins. You aren't just driving; you're managing a low-altitude flight where the ground is only inches away.

The engineering hurdles were immense. If the nose tilted up just a few degrees at 600 mph, the whole thing would become an unguided missile. If it pressed down too hard, the friction would shred the wheels or dig a trench into the Alvord Desert. They had to design a specialized suspension and steering system that could handle the immense vibration of a jet engine while maintaining a straight line on an imperfect surface.

Why 763 MPH Wasn't Enough

The target was always the record set by Andy Green in the ThrustSSC. That car—or rather, that twin-engine monster—hit 763.035 mph in 1997, becoming the first land vehicle to officially break the sound barrier. For the North American Eagle Project team, beating that wasn't just about pride. It was about proving that a small, dedicated team of volunteers could out-engineer a well-funded international operation.

They weren't just guessing. The team used intensive computational fluid dynamics (CFD) to figure out how the air would move around the cockpit and the tail. At those speeds, air stops acting like a gas and starts acting like a solid wall. Shockwaves form. If those shockwaves hit the ground and bounce back up under the car, it’s game over.

Throughout the 2000s and early 2010s, the project made several high-speed runs. They reached 317 mph, then 400, then 515. Each time, the team learned something new about the "Eagle." They weren't just testing a car; they were testing the limits of 1950s metallurgy and modern sensor arrays. They swapped out the original wheels for solid aluminum discs because rubber tires would simply explode under the centrifugal force of 800 mph rotations.

Jessi Combs and the Price of the Record

You can't talk about the North American Eagle Project without talking about Jessi Combs. She was a professional racer, a fabricator, and a TV personality, but more than that, she was fearless. She joined the project with the goal of becoming the "fastest woman on four wheels," a record held by Kitty O'Neil since 1976.

In 2013, Jessi set a mark of 398 mph. She was just getting started.

Then came August 27, 2019. The team was out in the Alvord Desert in Oregon. The conditions were right. Jessi was in the cockpit. During a high-speed run, something went catastrophically wrong. A mechanical failure in a front wheel—likely caused by hitting an object on the desert floor at nearly 500 mph—led to a crash that took her life.

🔗 Read more: Why NASA Hubble Space Telescope Images Still Rule Your Screen After 30 Years

It was a devastating blow to the racing world and a sobering reminder of why this record is so rarely challenged. The North American Eagle Project didn't just lose its driver; it lost its soul. In 2020, Guinness World Records posthumously awarded Jessi the record she was chasing: 522.783 mph. She did it. But the cost was ultimate.

The Technical Reality of Breaking the Sound Barrier on Land

A lot of people ask why we don't just put a bigger engine in a car and go. It’s the "C" word: Compressibility.

When a vehicle approaches Mach 1, the air in front of it can’t get out of the way fast enough. It piles up. This creates a sonic boom. On a plane, that's fine—you're surrounded by empty sky. On the ground, that shockwave is trapped between the belly of the car and the hard-packed silt of the desert. This creates "ground effect" issues that can literally flip a ten-ton vehicle like a pancake.

The North American Eagle used a unique "mid-engine" layout for its wheels. It had two wheels in the front (very close together) and two in the rear, tucked into the fuselage. This was meant to minimize the footprint and reduce the drag. Every rivet had to be flush. Every seam had to be perfect.

Why it's harder than flying:

- Friction: Airplanes don't have to worry about the rolling resistance of wheels spinning at 10,000 RPM.

- Surface: A desert looks flat until you're doing 500 mph. Then, a two-inch pebble becomes a ramp.

- Stopping: You can't just hit the brakes. You need a staged parachute system. If the chutes fire too early, they rip off. Too late, and you're out of desert.

The Legacy of the Eagle

So, where does the North American Eagle Project stand today? After Jessi's death, the project effectively halted. The vehicle itself is a piece of history, a testament to the era of "garage-built" land speed challengers. It represented a bridge between the old-school hot rodders and the new era of computer-aided aerospace engineering.

The project proved that the F-104 airframe could survive the transition to land, but it also highlighted the extreme danger of the pursuit. Today, the quest for 1,000 mph (the next big milestone) has mostly shifted to projects like Bloodhound LSR in the UK, which utilizes a combination of jet and rocket power.

But there was something uniquely American about the Eagle. It was scrappy. It was loud. It was built by guys who spent their own retirement money to see a needle move across a dial. They didn't have a massive government grant. They had a jet they found in a field and a dream that refused to die.

What We Can Learn from the Project

If you're a gearhead or a tech nerd, the North American Eagle Project is a masterclass in risk management and iterative design. They didn't try to go 800 mph on day one. They spent twenty years creeping up on the number.

The biggest takeaway? Data is everything. The team used over 100 sensors to monitor everything from exhaust gas temperature to the lateral G-loads on the chassis. In the end, it wasn't a lack of data that caused the tragedy; it was the inherent unpredictability of the environment. You can simulate a wind tunnel, but you can't simulate every square inch of a dry lake bed.

👉 See also: 821 Howard Street San Francisco: What’s Actually Happening at This SoMa Tech Hub

Actionable Insights for Speed Enthusiasts:

- Understand the Aero: If you're building anything for high speed, spend 90% of your time on downforce and 10% on horsepower. Power is easy; staying on the ground is hard.

- Redundancy is King: The Eagle used multiple parachute systems and secondary braking for a reason. In high-stakes engineering, "one" is the same as "none."

- Respect the Environment: The Alvord Desert and Bonneville Salt Flats are changing. Climate change and land use have made these surfaces more "crusty" and less predictable than they were in the 1960s.

- Support the Community: Land speed racing survives on volunteers. Organizations like the SCTA (Southern California Timing Association) are the backbone of this sport.

The North American Eagle Project remains a bittersweet chapter in the history of speed. It showed us the absolute limit of what a dedicated team can do with "obsolete" technology and reminded us that the sound barrier is a formidable wall, whether you're in the air or on the dirt.

To dig deeper into the actual telemetry and the physics of the runs, you can look into the archival data provided by the team's engineering partners. It’s a goldmine for anyone interested in fluid dynamics or jet propulsion. The Eagle may not be running today, but the lessons learned on those desert flats continue to influence how we think about high-speed stability and vehicle safety.