If you look at a standard Normandy D Day map today, it looks remarkably clean. You see five neat arrows—Utah, Omaha, Gold, Juno, Sword—pointing directly at the French coastline. It looks like a simple, logical plan. But the reality on June 6, 1944, was a chaotic, bloody mess that barely resembles those polished blue-and-red diagrams in history textbooks. Maps are liars. They flatten the terror of 150,000 men hitting the water at once.

The coast of Normandy isn’t just one long beach. It’s a jagged, 50-mile stretch of limestone cliffs, tidal flats, and marshy flooded fields. When planners at SHAEF (Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force) were drafting the actual invasion maps, they weren't just looking at where to land boats. They were obsessing over soil density, the height of sea walls, and whether a Churchill tank would sink into the mud the second it ramped off a landing craft. Honestly, if the geology had been slightly different, the map we study today wouldn't even exist.

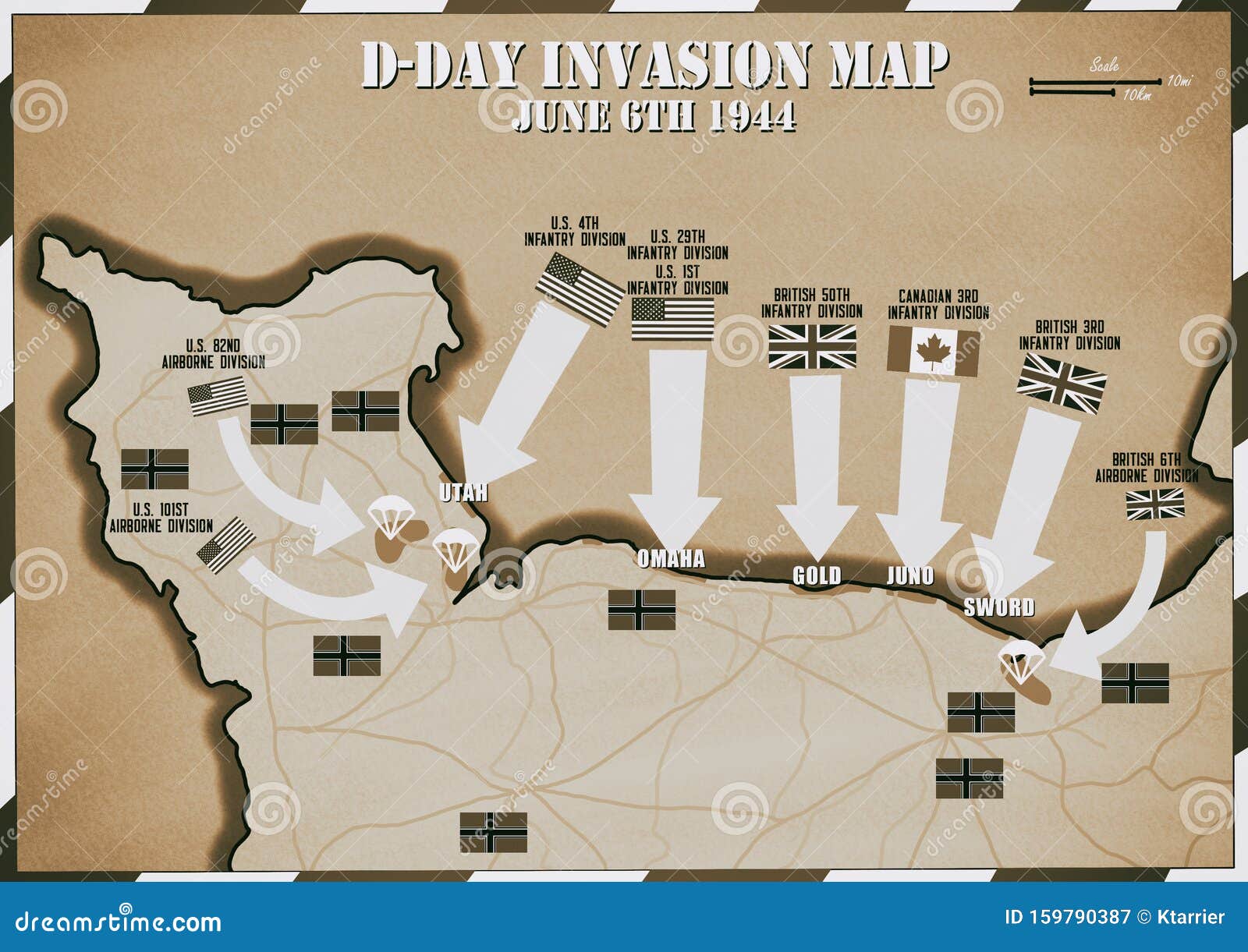

The Five Beaches Weren't Just Random Spots

It’s easy to think they just picked five spots and gave them cool codenames. Not really. Each sector on the Normandy D Day map was chosen for a specific strategic nightmare.

Utah Beach was added late in the planning. General Montgomery insisted on it because the Allies needed a port, and Utah was the gateway to Cherbourg. But look at a topographical map of that area from 1944. The Germans had flooded the land behind the dunes. There were only four narrow causeways leading off the beach. If the 4th Infantry Division didn't secure those exits, they’d be sitting ducks on a thin strip of sand.

Then you have Omaha. This is the one everyone knows from the movies. It’s a crescent-shaped death trap. On the map, it looks like a wide-open space, but in person, you realize the "bluffs" are actually steep hills that give the defenders a perfect view of everything. The 1st and 29th Infantry Divisions weren't just fighting soldiers; they were fighting a vertical landscape. Most of the aerial bombardment missed the German bunkers entirely, meaning the "map" the soldiers were given didn't match the reality of the intact defenses they actually faced.

Gold, Juno, and Sword—the British and Canadian sectors—were different. They had to deal with reefs and coastal towns. In places like Bernières-sur-Mer, the "front line" on the map was literally someone’s front door.

Why the Map Changes Depending on Who You Ask

Military historians often argue about where the "real" D-Day happened. Was it the beaches? Or was it the drop zones?

If you look at a paratrooper's Normandy D Day map, the beaches are almost irrelevant. Their world was the "Bocage"—the thick, ancient hedgerows of the Cotentin Peninsula. To the 101st and 82nd Airborne, a map was a suggestion at best. Because of heavy cloud cover and intense anti-aircraft fire, pilots dropped thousands of men miles away from their intended markers. Some ended up in the middle of flooded marshes and drowned under the weight of their own gear.

✨ Don't miss: Map Kansas City Missouri: What Most People Get Wrong

The maps they carried were often printed on silk so they wouldn't rustle or dissolve in the rain. Imagine standing in a dark French field, soaked to the bone, staring at a piece of silk trying to figure out which way is Sainte-Mère-Église. That is the disconnect between the "Big Map" at headquarters and the "Small Map" in a soldier's pocket.

Reading the Defenses: The Atlantic Wall

The German map of Normandy looked very different. Rommel, who was in charge of the defenses, viewed the map as a series of "resistance nests" (Widerstandsnester).

He knew he couldn't guard every inch of the 50 miles. Instead, he focused on the "draws"—the natural valleys and paths that led from the beach to the inland roads. If you find a detailed Normandy D Day map that shows German positions, you’ll see clusters of artillery (WN-62 at Omaha is the most famous) positioned to fire across the beach, not just straight out to sea. This "interlocking fire" meant that no matter where a boat landed, it was in the crosshairs of at least two different bunkers.

The obstacles were another layer. At low tide, the map of the beach itself changed. Rommel installed "Hedgehogs," Cointet-elements, and "Hemmbalken" (wooden ramps tipped with mines). The Allies had to land at low tide to see these obstacles, which meant the soldiers had to run across 300 yards of open sand.

Think about that. 300 yards. That's three football fields.

Under fire.

The map doesn't show the exhaustion of running that distance in wet wool uniforms.

🔗 Read more: Leonardo da Vinci Grave: The Messy Truth About Where the Genius Really Lies

The "Map" of Deception: Operation Fortitude

One reason the Normandy D Day map worked is because the Allies created a fake one.

Operation Fortitude was a massive "fake news" campaign to convince Hitler that the landing was happening at the Pas-de-Calais, the narrowest part of the English Channel. They built inflatable tanks. They created a "Ghost Army" under General Patton. They even sent fake radio signals.

The German high command was so convinced by their own maps of the "expected" invasion that even when the boats started hitting the sand in Normandy, they kept their best Panzer divisions in reserve near Calais. They thought Normandy was a diversion. By the time they realized the map in Normandy was the real one, it was too late. The bridgehead was secure.

Logistics: The Map Behind the Map

We talk about the fighting, but the Normandy D Day map is also a map of pipes and ports.

Ever heard of PLUTO? It stands for "Pipe-Lines Under The Ocean." The Allies actually laid a fuel pipe across the bottom of the English Channel. They also towed over two giant artificial harbors called "Mulberries."

If you visit Arromanches today, you can still see the massive concrete caissons of the Mulberry B harbor sitting in the water. On a 1944 logistical map, these were the lungs of the operation. Without them, the Allied army would have run out of bullets and bread within a week. The map of the invasion isn't just a line of battle; it's a massive plumbing project that moved millions of tons of steel and fuel from England to France.

Navigating the Modern Normandy Landscape

If you're planning to visit, you've gotta understand that the Normandy D Day map has two layers: the 1944 reality and the 2026 tourist infrastructure.

💡 You might also like: Johnny's Reef on City Island: What People Get Wrong About the Bronx’s Iconic Seafood Spot

You can't "do" Normandy in a day. It’s too big. Most people try to rush from the American Cemetery at Colleville-sur-Mer over to Arromanches and then maybe to Pegasus Bridge. You'll spend the whole time in a car.

Instead, pick a sector.

If you want the "map" to come alive, go to Pointe du Hoc. This is where the Rangers scaled 100-foot cliffs. The craters from the naval bombardment are still there. It looks like the surface of the moon. Standing on the edge of that cliff, looking down at the tiny strip of rocks below, you realize how insane the topographical map must have looked to the guys who had to climb it.

Common Misconceptions About the Geography

- The weather was a surprise. Not really. The Allies knew the weather sucked. They had a tiny window of "acceptable" conditions. The map of the English Channel's weather patterns was the most scrutinized document in history that week.

- The landings were perfectly coordinated. Absolute chaos. Most units landed in the wrong place. On Utah Beach, Brigadier General Theodore Roosevelt Jr. realized they were a mile off target and famously said, "We’ll start the war from right here."

- The Atlantic Wall was an impenetrable wall. It was more of a series of strongpoints. There were huge gaps. The "map" of German defenses was much thinner in some places than the Allies feared.

The Map That Saved the World

Ultimately, the Normandy D Day map is a record of a miracle.

It’s a miracle of coordination. Think about the fact that they managed to coordinate thousands of ships and planes without GPS, without cell phones, and without digital mapping software. Everything was hand-drawn. Everything was calculated with slide rules.

When you look at the map today, don't just see the arrows. See the villages like Colleville, Vierville, and Saint-Laurent. See the "hedgerows" that aren't marked on the big maps but cost thousands of lives to clear. See the cemeteries that now dot the coastline, which are the final, somber entries on the map of this campaign.

Actionable Steps for Exploring D-Day History

If you really want to understand the geography of the invasion, don't just look at a screen.

- Get a physical IGN Map. The French "Institut Géographique National" produces highly detailed 1:25,000 maps. Look for the "Espaces Guerres et Mémoires" editions. They show the exact bunkers and trench lines that are still visible in the woods today.

- Visit at low tide. If you want to see the "map" the soldiers saw, you have to be there when the tide is out. The scale of the beaches is mind-blowing when the water recedes.

- Check out the Overlord Museum. It's right near Omaha Beach. They have incredible displays of the actual equipment used to map and navigate the terrain.

- Use the "D-Day 75" (or latest) apps. There are several AR (Augmented Reality) apps that allow you to hold your phone up at locations like Juno Beach and see the 1944 map overlaid on the modern buildings.

- Walk the "Sentier des Douaniers." This is the old customs path that runs along the cliffs. Walking from Omaha to the battery at Longues-sur-Mer gives you a perspective of the height and distance that no car ride can provide.

The story of D-Day is written in the dirt and the sand. The map is just our way of trying to make sense of the courage it took to cross those 50 miles.