Honestly, if you close your eyes and think of "Norman Rockwell famous works," you probably see a turkey. Specifically, that massive, glistening bird being lowered onto a table in Freedom from Want. It’s the ultimate "Grandma’s house" vibe. For decades, that was the brand. People called him a "nostalgia merchant" or a "kitsch" artist.

But here is the thing.

The guy was actually kinda' radical. If you only know him for the rosy-cheeked kids and the "shucks, golly" Americana, you’re missing the most interesting half of the story. Rockwell wasn't just a guy with a paintbrush; he was a master storyteller who eventually got tired of telling the "polite" version of the American dream.

The Saturday Evening Post Era: More Than Just Covers

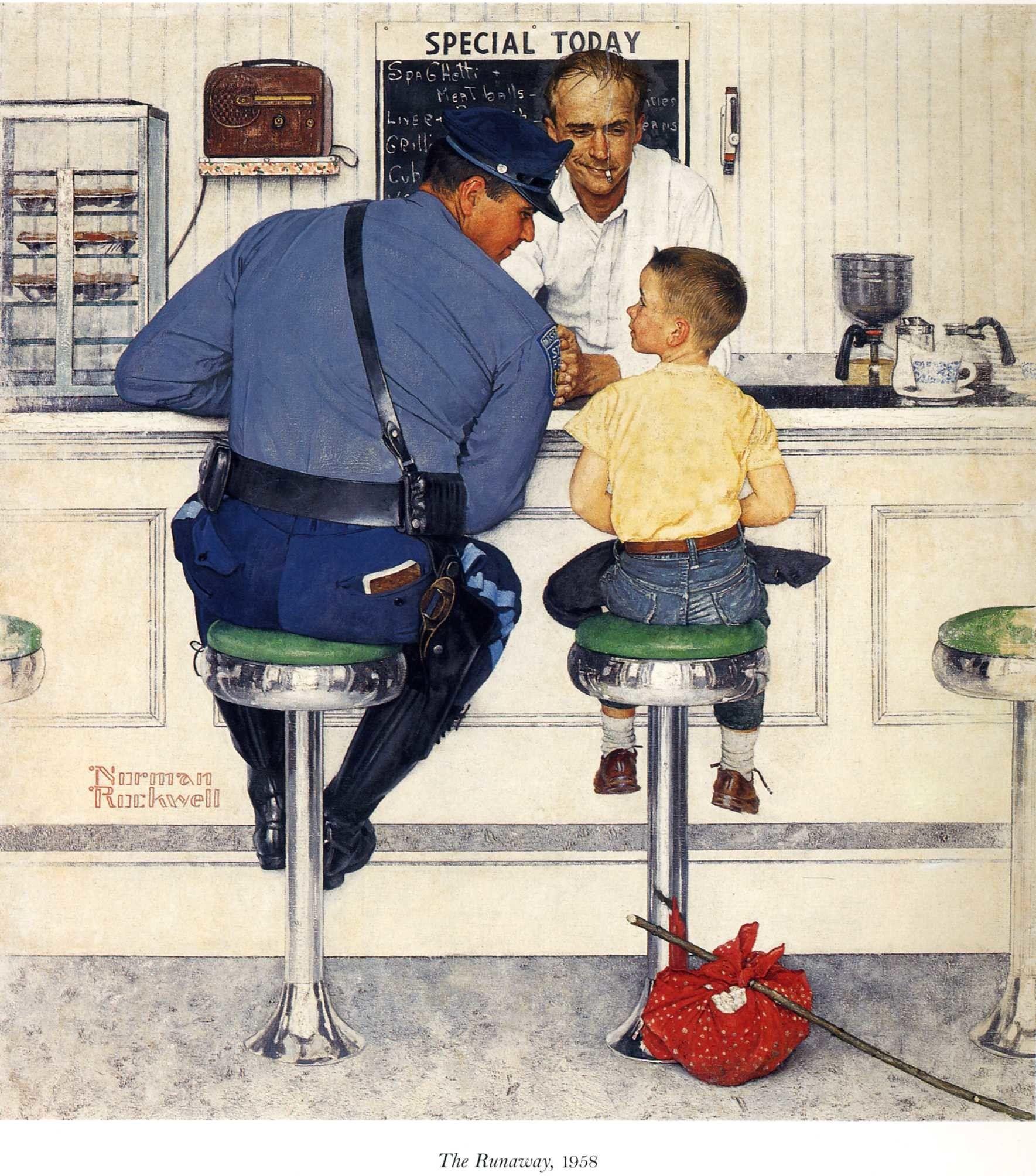

For 47 years, Rockwell was the face of The Saturday Evening Post. We’re talking 322 covers. That is a staggering amount of work. This is where he built that "Rockwellian" aesthetic we all recognize. You know the ones: the doctor listening to a doll's heartbeat, the runaway boy at the diner, the "Triple Self-Portrait" where he’s looking at himself in a mirror while painting himself.

But there was a catch.

The Post had some pretty strict, and frankly outdated, rules. Back then, they basically told Rockwell he could only paint minorities if they were in "servile" roles—think maids or train porters. It’s a cringey part of history, but it’s the reality he worked in for nearly half a century.

The Four Freedoms (1943)

If we’re talking about Norman Rockwell famous works, this is the heavyweight champion. Inspired by FDR’s 1941 State of the Union address, Rockwell spent seven months obsessed with these four paintings:

👉 See also: Charlie Charlie Are You Here: Why the Viral Demon Myth Still Creeps Us Out

- Freedom of Speech: A blue-collar man standing up at a town meeting. He looks like a regular guy, but everyone is listening.

- Freedom of Worship: A close-up of people praying, representing different faiths.

- Freedom from Want: The famous Thanksgiving dinner.

- Freedom from Fear: Parents tucking their kids into bed while holding a newspaper with headlines about the war.

These weren't just pretty pictures. They were a massive fundraising tool. The government took them on a tour across 16 cities, and they helped raise over $132 million in war bonds. That is "save the world" money in 1940s terms.

The Breaking Point and the Move to Look Magazine

By the early 1960s, Rockwell was done. He was tired of the "best of all possible worlds" mandate. In 1963, he quit the Post and headed to Look magazine. This is where the "Grandpa" of American art started showing some serious teeth.

At Look, they gave him total freedom. He stopped painting puppies and started painting the evening news.

The Problem We All Live With (1964)

This might be his most important painting, period. It shows six-year-old Ruby Bridges walking into an all-white school in New Orleans. You’ve got the four U.S. Marshals (their heads are cropped out to make Ruby the focus), the splattered tomato on the wall, and the racial slur clearly visible in the background.

It’s a gut-punch.

When it was published, the hate mail came in waves. People called him a "traitor." But Rockwell didn't care. He famously said that for 47 years he’d portrayed the best of all possible worlds, but that "that kind of stuff is dead now."

✨ Don't miss: Cast of Troubled Youth Television Show: Where They Are in 2026

The Secret Technique: He Wasn't Just "Winging It"

There’s a common misconception that Rockwell just sat down and painted from his imagination. Nope. He was basically a movie director.

He used a camera. A lot.

Starting in the 1930s, he would hire neighbors—never professional models—and pose them in incredibly specific ways. He’d shout instructions, use props, and snap hundreds of photos. He once said he’d "wrung" the expressions out of his models. He wanted that hyper-realistic, "caught in the moment" feel.

Take Rosie the Riveter (1943), for example. The model was a 19-year-old phone operator named Mary Doyle Keefe. She was actually quite petite, but Rockwell painted her with massive, muscular arms and had her stomping on a copy of Mein Kampf. He wanted her to look like a powerhouse.

Why These Works Still Hit Different Today

It’s easy to dismiss Rockwell as "old-fashioned," but if you look at a painting like The Golden Rule (1961), you see a guy who was genuinely trying to figure out how people get along. That painting—which is now a massive mosaic at the United Nations—features people of all different races and religions standing together.

It’s simple, sure. Maybe a little idealistic. But in a world that feels increasingly polarized, that "idealism" feels less like a cliché and more like a challenge.

🔗 Read more: Cast of Buddy 2024: What Most People Get Wrong

Misconceptions to Clear Up

- "He only painted white people." True for a long time because of the Post's rules, but his later work for Look was some of the most pro-Civil Rights art in mainstream media.

- "He’s a Vermont artist." He lived in Arlington, VT for 14 years, but the actual Norman Rockwell Museum is in Stockbridge, Massachusetts. That's where he spent his final 25 years.

- "He was just an illustrator, not an artist." This debate is old. While he was commercial, his technical skill and the way he composed his scenes are now studied by serious art historians and filmmakers like Steven Spielberg and George Lucas (who are both huge fans and collectors).

How to Experience Rockwell Properly

If you actually want to get a feel for Norman Rockwell famous works without just scrolling through Google Images, here is the move.

Go to Stockbridge. The Norman Rockwell Museum there holds the largest collection of his original stuff. Seeing the scale of the Four Freedoms in person is a totally different experience than seeing them on a postcard. They are huge, and the detail in the brushwork—the way he captures the texture of a wool coat or the skin on an old man’s hand—is wild.

Read "My Adventures as an Illustrator." It’s his autobiography. It’s funny, self-deprecating, and gives you a real look at how much he struggled with his "illustrator" label.

Look at the "Murder in Mississippi" sketches. If you think he was all sunshine and rainbows, look up his 1965 painting about the killing of civil rights workers. It’s dark, moody, and deeply haunting. It proves he could handle tragedy just as well as he handled comedy.

Basically, stop looking at the turkey and start looking at the people. Rockwell wasn't just painting what America was; he was painting what he hoped it could be, and eventually, he wasn't afraid to paint where it was failing. That's what makes him a legend.

To see the progression for yourself, start by comparing his 1920s Post covers with his 1960s Look illustrations side-by-side. The shift in tone isn't just an artistic change; it’s a front-row seat to the evolution of the American conscience.