You've probably seen the ads. They pop up on financial news sites or in your brokerage feed promising 10%, 11%, or even 12% annual returns. In a world where standard savings accounts often feel like they’re barely treading water against inflation, those numbers look like a life raft. Usually, these offers are for NCDs. But before you move your life savings, you need a solid non convertible debentures definition that actually makes sense in the real world, not just in a textbook.

Basically, an NCD is a long-term financial instrument issued by companies to raise money from the public. It’s a debt. You are the lender; the company is the borrower.

Here is the kicker: unlike "convertible" debentures, these cannot be turned into equity shares later on. You won't ever own a piece of the company. You just get your interest (the coupon) and, hopefully, your principal back at the end. It’s a pure loan. If the company grows ten times over, you don't get a slice of that pie. You just get your agreed-upon interest.

The Anatomy of a Non Convertible Debenture

Think of an NCD as a formal "I owe you" with a lot of legal weight. Companies like Tata Capital, Muthoot Finance, or even smaller NBFCs (Non-Banking Financial Companies) use these to fund their growth or manage daily operations.

They need cash. You have cash.

The agreement is simple. You give them $10,000 (or the equivalent in your local currency). They promise to pay you $1,000 every year for five years. At the end of that fifth year, they hand back your $10,000.

But why "non convertible"?

In the old days—and still today in certain private equity circles—convertible debentures were popular because they gave investors a "sweetener." If the company did well, you could swap your debt for stock. NCDs stripped that away. To make up for the lack of an "equity upside," companies have to offer higher interest rates. That’s the trade-off. You give up the chance to own the company in exchange for a bigger check every month or year.

Secured vs. Unsecured: The Safety Net

This is where things get real. Honestly, most people skip the fine print here, and that’s a massive mistake.

🔗 Read more: Is The Housing Market About To Crash? What Most People Get Wrong

Secured NCDs are backed by the company’s assets. If the business goes belly up, the liquidator sells off the machinery, the office building, or the land to pay you back. You’re at the front of the line.

Unsecured NCDs are the opposite. They are backed only by the company’s "word" and creditworthiness. If they go bankrupt, you’re standing at the back of a very long line, right next to the equity shareholders, hoping there’s a few crumbs left in the jar.

Because unsecured NCDs are riskier, they almost always pay a higher interest rate. Is an extra 2% worth the risk of losing 100% of your principal? That’s the question you’ve got to answer.

The Credit Rating Trap

You can't talk about a non convertible debentures definition without mentioning agencies like CRISIL, ICRA, or CARE. These guys grade NCDs like a school report card.

AAA is the gold standard. It means the company is incredibly likely to pay you back. As you move down to AA, A, BBB, and so on, the risk of "default" (the company saying "oops, we don't have your money") increases.

Don't be fooled. Ratings aren't crystal balls.

Remember IL&FS? It was a giant in the infrastructure space. It had high ratings right until it didn't. When it collapsed, it sent shockwaves through the NCD market. A rating is just an opinion based on past data. It’s not a guarantee. If you see an NCD offering a return that seems "too good to be true"—say, 5% higher than the market average—check the rating immediately. Usually, that high yield is there to compensate for a balance sheet that looks like a disaster zone.

Tax Man Cometh: The Reality of Returns

People get blinded by the "headline rate."

💡 You might also like: Neiman Marcus in Manhattan New York: What Really Happened to the Hudson Yards Giant

"Look, it's 11%!"

Wait. How is it taxed?

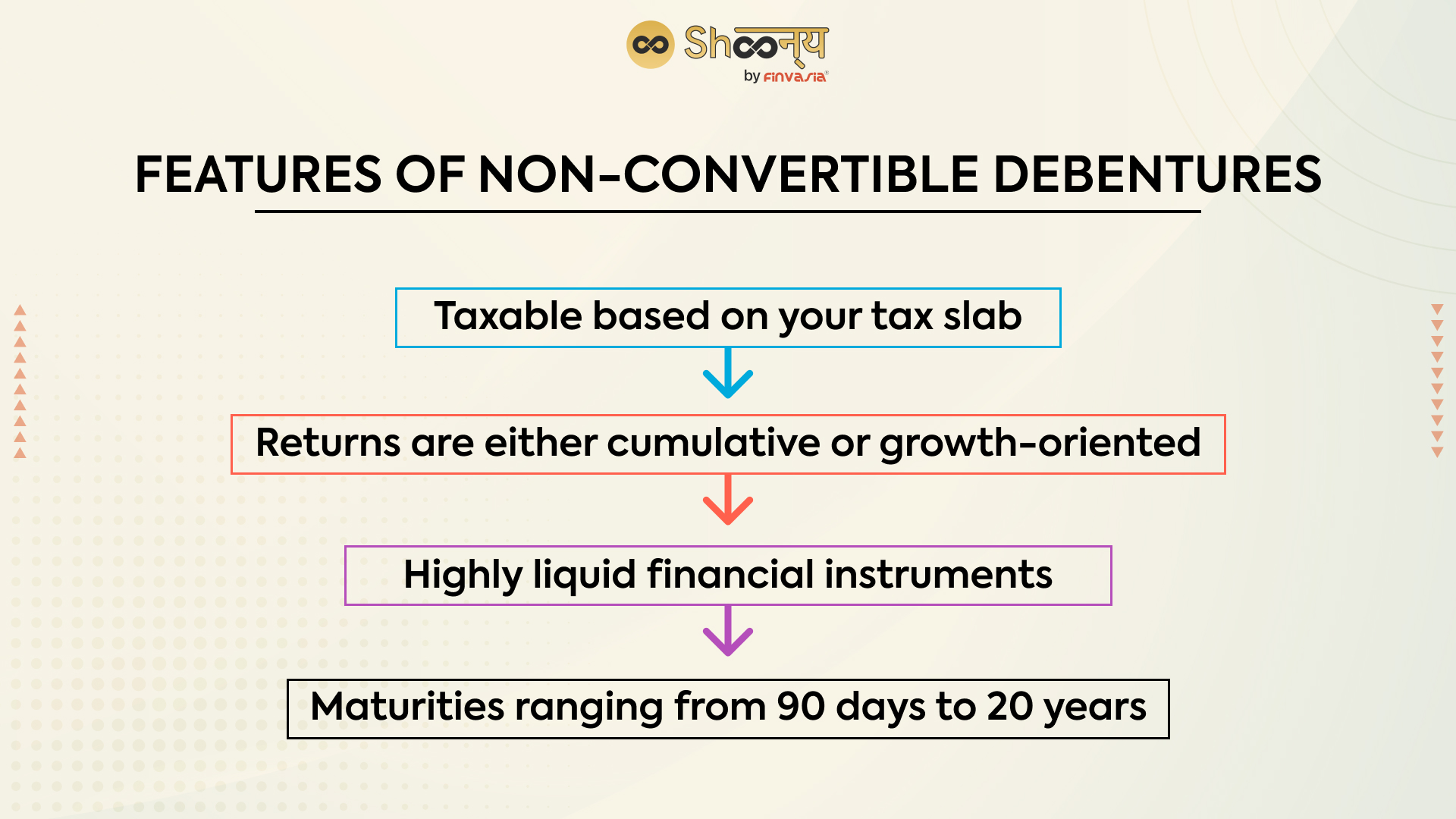

In many jurisdictions, NCD interest is taxed at your slab rate. If you're in the highest tax bracket, that 11% can quickly dwindle to something much less impressive after the government takes its cut.

However, there’s a bit of a loophole for the savvy. If the NCD is listed on a stock exchange and you sell it after holding it for more than a year, you might qualify for Long Term Capital Gains (LTCG) tax, which is often lower than the income tax rate.

Sorta makes you rethink the "hold until maturity" strategy, doesn't it?

Liquidity: The "Locked Door" Problem

NCDs are technically liquid because they are listed on exchanges. You should be able to sell them like a stock, right?

In theory, yes. In practice, maybe not.

The NCD market for retail investors is often "thin." This means there aren't many buyers and sellers active at any given moment. If you suddenly need your money back to pay for a medical emergency, you might find that the "market price" for your NCD is much lower than what you paid, simply because there’s no one on the other side of the trade.

📖 Related: Rough Tax Return Calculator: How to Estimate Your Refund Without Losing Your Mind

You could be stuck holding the bag until the maturity date, whether you like it or not.

Comparing NCDs to Fixed Deposits

Why not just put the money in a bank?

Bank Fixed Deposits (FDs) are generally seen as the "safest" bet. In many countries, bank deposits are insured up to a certain limit by the government. NCDs have no such insurance.

- FDs: Lower risk, lower return, high liquidity (usually with a small penalty).

- NCDs: Higher risk, higher return, variable liquidity.

If you’re a retiree looking for absolute certainty, NCDs should only be a tiny fraction of your portfolio. If you’re younger and can handle some volatility, they can be a great way to juice your fixed-income returns.

Putting it All Together: Is it for You?

Understanding the non convertible debentures definition is only half the battle. The other half is honest self-reflection.

You need to look at your portfolio. Are you already heavy on debt? Do you have an emergency fund?

NCDs are great for diversifying. They offer a steady stream of income that doesn't fluctuate with the stock market's daily tantrums. But they aren't "set it and forget it" investments. You have to monitor the company’s health. If you see news that the company’s debt-to-equity ratio is spiraling or that they’re struggling to pay other creditors, you might need to bail out early, even at a loss.

Critical Checklist Before Buying

- Check the Security: Is it secured by hard assets or just a promise?

- Verify the Rating: Don't just take the company's word. Go to the rating agency's website.

- Understand the Interest Options: Do you want "cumulative" (get all the interest at the end) or "periodic" (monthly/yearly payouts)?

- Look at the Tenure: Are you comfortable locking this money away for 3, 5, or 10 years?

- Evaluate the Issuer: Is this a household name or a fly-by-night operation that just popped up?

Actionable Next Steps

- Audit your current fixed-income holdings. If you only have bank FDs, look for "AAA" rated NCDs from blue-chip companies to increase your overall yield by 1-2%.

- Read the Prospectus. It’s boring. It’s long. It’s written in legalese. Read it anyway. Look specifically for the "Risk Factors" section. Companies are legally required to tell you exactly how they might fail in that section.

- Diversify across issuers. Never put all your NCD money into one company. Even the giants can stumble. Spread your investment across three or four different industries—maybe a housing finance company, a power company, and a diversified NBFC.

- Monitor interest rate cycles. When central bank interest rates go up, the value of existing NCDs usually goes down. If you think interest rates are about to peak, that’s often the best time to lock in a high-yield NCD for the long term.

- Set up a "ladder." Buy NCDs with different maturity dates—one maturing in 2 years, one in 4 years, and one in 6 years. This ensures you have cash coming in at regular intervals and aren't trapped if you need liquidity.