Ever sat there wondering why some random author from a country you can barely find on a map just won the world's most famous book prize? It happens every October. The Swedish Academy stands behind those big wooden doors, a guy in a suit steps out, and suddenly someone like László Krasznahorkai or Han Kang is a household name—or at least, a name people pretend to know at dinner parties.

Honestly, the Nobel Prize in Literature laureates list is a bit of a chaotic mess. It’s not just about who wrote the "best" book. If it were, Leo Tolstoy and Mark Twain wouldn't have been snubbed back in the day. It’s about "ideal direction," a phrase Alfred Nobel tossed into his will that has kept eighteen Swedes arguing in a basement for over a century.

The Secret World of the Swedish Academy

You can't just apply for this. Don't even try.

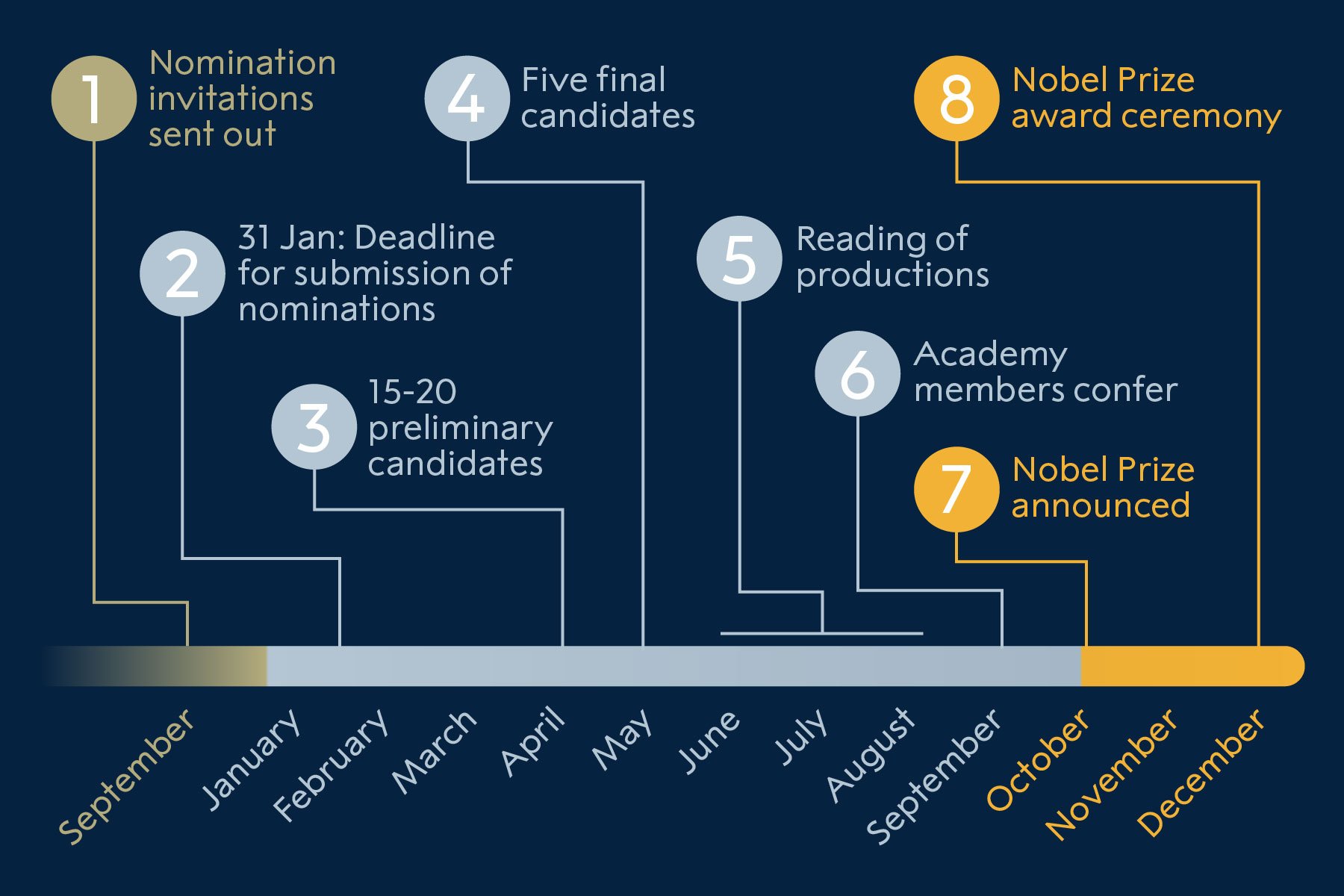

The selection process is shrouded in so much secrecy that the actual deliberations are locked away for 50 years. We won't know why Jon Fosse won in 2023 over, say, Salman Rushdie or Margaret Atwood, until the year 2073. Kind of wild, right? Basically, the Academy sends out thousands of letters to professors, former winners, and PEN clubs. They get back about 200 to 300 names. By summer, they’ve whittled it down to a "shortlist" of five.

Then they read. They read everything.

✨ Don't miss: Temuera Morrison as Boba Fett: Why Fans Are Still Divided Over the Daimyo of Tatooine

Why your favorite author probably won't win

The Academy doesn't care about the New York Times Bestseller list. They actually seem to dislike it. They look for "poetic prose that confronts historical traumas" (that was the 2024 vibe for Han Kang) or "clinical acuity" (Annie Ernaux in 2022). If an author is too commercial, the Academy tends to look the other way. They want someone who shifts the tectonic plates of literature.

Recent Winners You Should Actually Read

Let’s look at the heavy hitters from the last few years. It’s been a weird, eclectic mix.

- László Krasznahorkai (2025): The Hungarian master of the "marathon sentence." His stuff is dystopian and melancholic. If you like feeling a sense of impending doom but in a really beautiful, artistic way, he's your guy.

- Han Kang (2024): The first South Korean and first Asian woman to grab the medal. The Vegetarian is her big one. It’s visceral. It’s about a woman who stops eating meat and basically tries to turn into a plant. It’s way more intense than it sounds.

- Jon Fosse (2023): A Norwegian playwright who writes in Nynorsk. His work is "incantatory." It feels like a prayer or a fever dream. His Septology is a 1,250-page monologue. No, I’m not joking.

- Annie Ernaux (2022): She basically invented "autofiction" or "socio-biography." She writes about her illegal abortion in the 60s, her father’s death, and her own affairs with a cold, sharp precision. It’s short, punchy, and brutal.

The Politics and the Scandals

It hasn't always been about the books. In 2018, the whole thing imploded. A massive sexual misconduct and financial scandal involving Jean-Claude Arnault (the husband of an Academy member) led to a bunch of resignations. They didn't even give out a prize that year. They had to hand out two in 2019 to make up for it—Olga Tokarczuk and the very controversial Peter Handke.

People were mad. Handke had supported Slobodan Milošević, and many felt he shouldn't be honored. It reminded everyone that the Nobel is, at its heart, a political beast.

🔗 Read more: Why Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy Actors Still Define the Modern Spy Thriller

They’ve also been roasted for being too "Eurocentric." For a long time, it felt like you had to be a white guy from Europe to get a look-in. They’ve tried to fix that lately. Picking Abdulrazak Gurnah in 2021 was a huge move. He’s a Tanzanian-born British writer who writes about the refugee experience. Before he won, most bookstores didn't even have his books in stock. Overnight, he went from "who?" to the most important voice on colonialism in the world.

Does the Prize Still Matter?

Some say it’s an outdated relic.

Maybe. But the "Nobel Effect" is real. When Louise Glück won in 2020, her poetry sales went through the roof. It gives authors from smaller languages—like Hungarian or Nynorsk—a global stage they would never get otherwise. It’s sort of a "Quality Control" seal for the world’s libraries.

But honestly? It’s also just fun to argue about. Every year, Haruki Murakami fans get their hopes up, and every year, the Academy picks someone who writes about 19th-century salt mines in the Andes or something.

💡 You might also like: The Entire History of You: What Most People Get Wrong About the Grain

How to dive into Nobel literature without getting bored

- Start with the short stuff. Don't jump into Fosse’s Septology. Try Annie Ernaux’s A Man’s Place. It’s like 90 pages.

- Look for the "International Booker" crossover. Many recent winners like Han Kang and Tokarczuk won the International Booker first. That’s usually a sign the book is actually readable and not just "important."

- Read the "Nobel Lecture." Every winner gives a speech. Usually, it’s the best introduction to why they write. Han Kang’s "Light and Thread" is a great place to start.

If you want to understand the modern world, you sort of have to look at what the Nobel Prize in Literature laureates are saying. They aren't writing for the "now." They’re writing for the "forever." It’s heavy, it’s complicated, and sometimes it’s even a little pretentious—but it’s never boring once you get into the story behind the person.

Check out your local library’s "Nobel" shelf. Pick the book with the weirdest cover. You might just find your new favorite writer in the most unexpected place.

Next Steps for Your Reading List:

To truly appreciate these laureates, begin with Abdulrazak Gurnah's Afterlives for a perspective on colonial history that rarely makes the textbooks, or pick up Han Kang’s Human Acts to see how literature can process national trauma. If you prefer poetry, the late Louise Glück's The Wild Iris offers an accessible yet profound entry point into why the Swedish Academy still values the "unmistakable poetic voice."