In 1945, a young woman named Fawn Brodie did something that, at the time, felt like a literal act of war in the American West. She published No Man Knows My History, a biography of Joseph Smith that didn't just ruffle feathers—it scorched the earth. Imagine being the niece of a high-ranking Mormon apostle and then writing a book that basically calls the founder of your family's faith a brilliant, charismatic con man.

It was gutsy. It was also, for Brodie, a one-way ticket out of the Church.

The LDS Church excommunicated her almost immediately. But here is the thing: decades later, her book is still the ghost that haunts every conversation about Mormon origins. Whether you think she was a pioneer of honest history or a "bird fouling her own nest" (as her uncle David O. McKay put it), you can't talk about Joseph Smith without talking about Brodie.

👉 See also: That Cat With Thumb Up Meme: Why Polydactyl Cats Are Taking Over Your Feed

Why the Title "No Man Knows My History" Still Matters

The title comes from a sermon Smith gave shortly before he was killed in Carthage, Illinois. He told a crowd, "You don't know me; you never knew my heart. No man knows my history." Brodie took that as a challenge. She wanted to prove that a human life, even one as wrapped in gold plates and angelic visitations as Smith’s, could be decoded using standard historical tools.

She basically stripped away the Sunday School varnish.

Before Brodie, most books about Joseph Smith were either "hagiographies" (super-polished, saintly fluff) or "anti-Mormon" rants that were so biased they weren't even readable. Brodie tried a third path. She treated him like a psychological puzzle. She saw a man who was deeply imaginative, someone who could weave the local folklore of New York—treasure digging, folk magic, and the "Indian mound" myths—into a brand-new American religion.

The "Fraudulent Genius" Theory

Brodie’s central argument was that Joseph Smith was a "genius of improvisation." She didn't think he was just a simple liar. Instead, she painted him as someone who started with a small deception and eventually began to believe his own myth.

- Treasure Hunting: She was one of the first to really dig into Smith's early days as a "money digger" using seer stones.

- The First Vision: She famously argued that the 1820 vision was a later "concoction," pointing out that Smith didn't mention it in early records.

- The Book of Mormon: She claimed it wasn't a translation of ancient plates but a "highly original and imaginative fiction" fueled by the 19th-century atmosphere.

Honestly, it’s a compelling read even if you disagree with her. Her prose is sharp. She writes like a novelist, which is probably why the book has stayed in print for eighty years while more "academic" books have gathered dust.

What Brodie Got Right (and Where She Missed)

History is a messy business. When you’re writing in 1945, you don’t have the internet or the "Joseph Smith Papers" project. You have old newspapers, hostile neighbors' affidavits, and a Church archive that, at the time, was mostly locked tight.

The Wins

Brodie was right about a lot of the "hard" facts that the Church tried to ignore for years. She was open about Smith’s polygamy when the official narrative was still very quiet about it. She correctly identified that he had dozens of wives, including some who were already married to other men (polyandry).

👉 See also: Why the Last Three Verses of Surah Baqarah are the Most Powerful Dua You’ll Ever Read

She also nailed the connection between Mormonism and the "Burned-over District" of New York. She understood that Smith wasn't living in a vacuum; he was soaking up the revivalist energy and the political anxieties of his time.

The Misses

Modern scholars, even the skeptical ones, think Brodie leaned too hard into "psychobiography."

She’d write things like, "Joseph must have felt a pang of guilt here," or "He was thinking X when he did Y." You can’t really know what a guy from 1840 was thinking. It’s a bit of a stretch.

Also, DNA testing has debunked some of her theories. Brodie speculated that Smith had fathered children with several of his plural wives. Recent genetic studies have shown that in many of the cases she cited, Joseph wasn't the father.

There's also the "religious" problem. Critics like Marvin Hill have argued that Brodie made Smith too secular. By painting him as a pure manipulator, she missed the fact that he seemed to genuinely believe in his mission. People don't usually walk into a hail of bullets at a jailhouse just for a "con." There was a level of sincerity there that Brodie’s "fraud" narrative struggles to explain.

The Legacy of a "Heretic"

If you go to a Mormon bookstore today, you won’t find No Man Knows My History on the shelf. But you will find books like Richard Bushman’s Rough Stone Rolling.

Bushman is a faithful LDS scholar, but his book—which is now widely accepted—deals with many of the same difficult topics Brodie brought up in 1945. In a weird way, Brodie paved the path for "The New Mormon History." She forced the conversation into the light.

You've got to respect the sheer impact. Most biographies are forgotten in five years. This one is a permanent fixture in the American religious landscape.

Actionable Insights for Readers

If you're planning to dive into Brodie’s work, here is how to handle it:

- Read it for the narrative: It is a masterpiece of storytelling. Treat it as a "foundational text" of Smith biography.

- Cross-reference with modern sources: Look at the Gospel Topics Essays on the LDS website or the Joseph Smith Papers. See where the Church now admits facts that Brodie was excommunicated for mentioning.

- Watch for the bias: Remember that Brodie was writing her way out of a faith. Her "naturalistic" lens means she will never accept a supernatural explanation, even if it’s the only one that fits the behavior of the people involved.

- Check the footnotes: Brodie was a meticulous researcher for her time, but some of her sources were biased "anti-Mormon" affidavits from the 1830s. Take them with a grain of salt.

The reality is that No Man Knows My History isn't just a book about a dead prophet. It's a book about how we construct our own identities. For Brodie, writing it was her "declaration of independence." For the reader, it remains a fascinating look at the man who started one of the most successful religious movements in history.

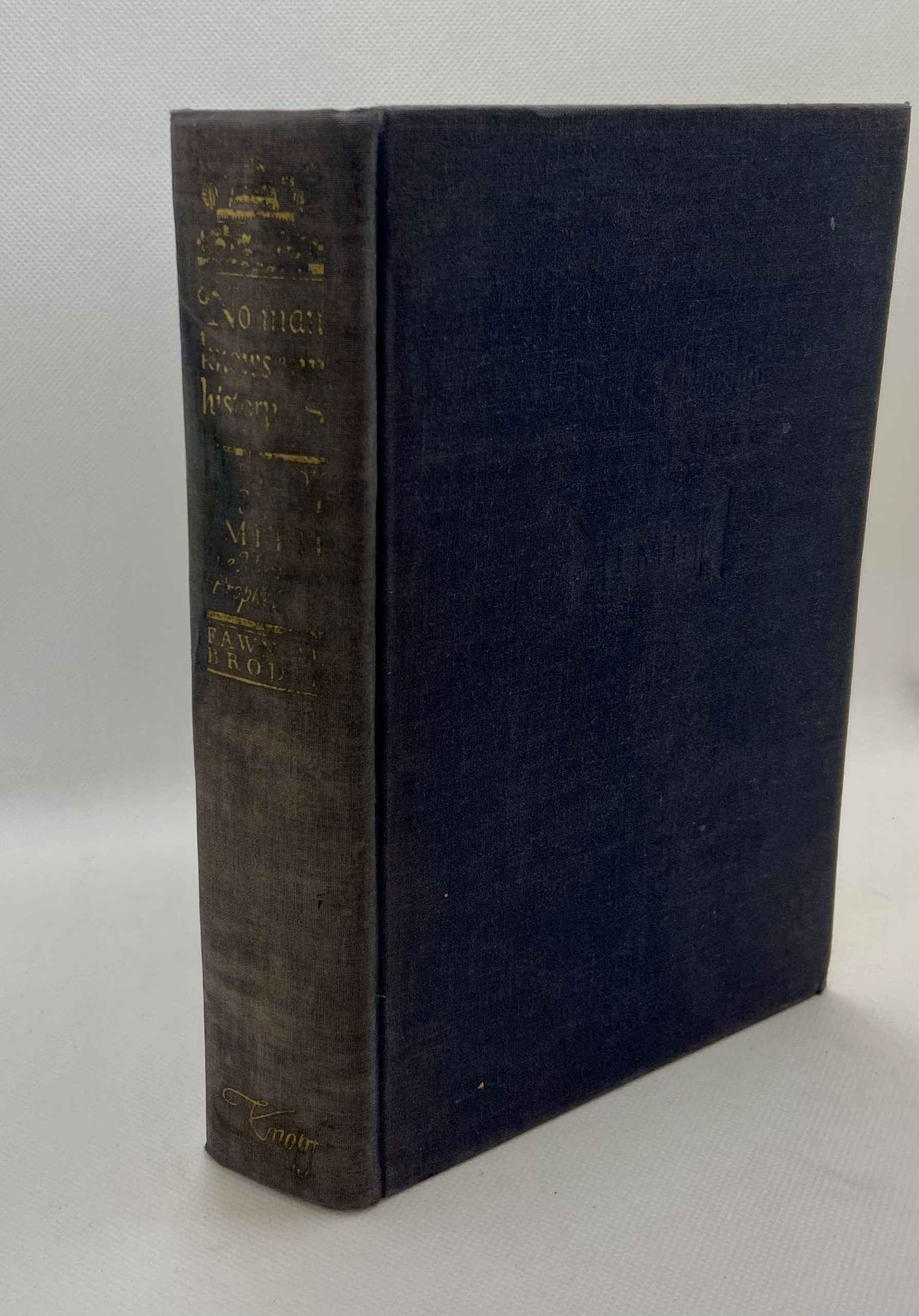

To truly understand the story, look for the 1971 revised edition. It contains a supplement where Brodie tries to address her critics and incorporates more of the psychological theories that became her trademark. It's the most complete version of her vision.