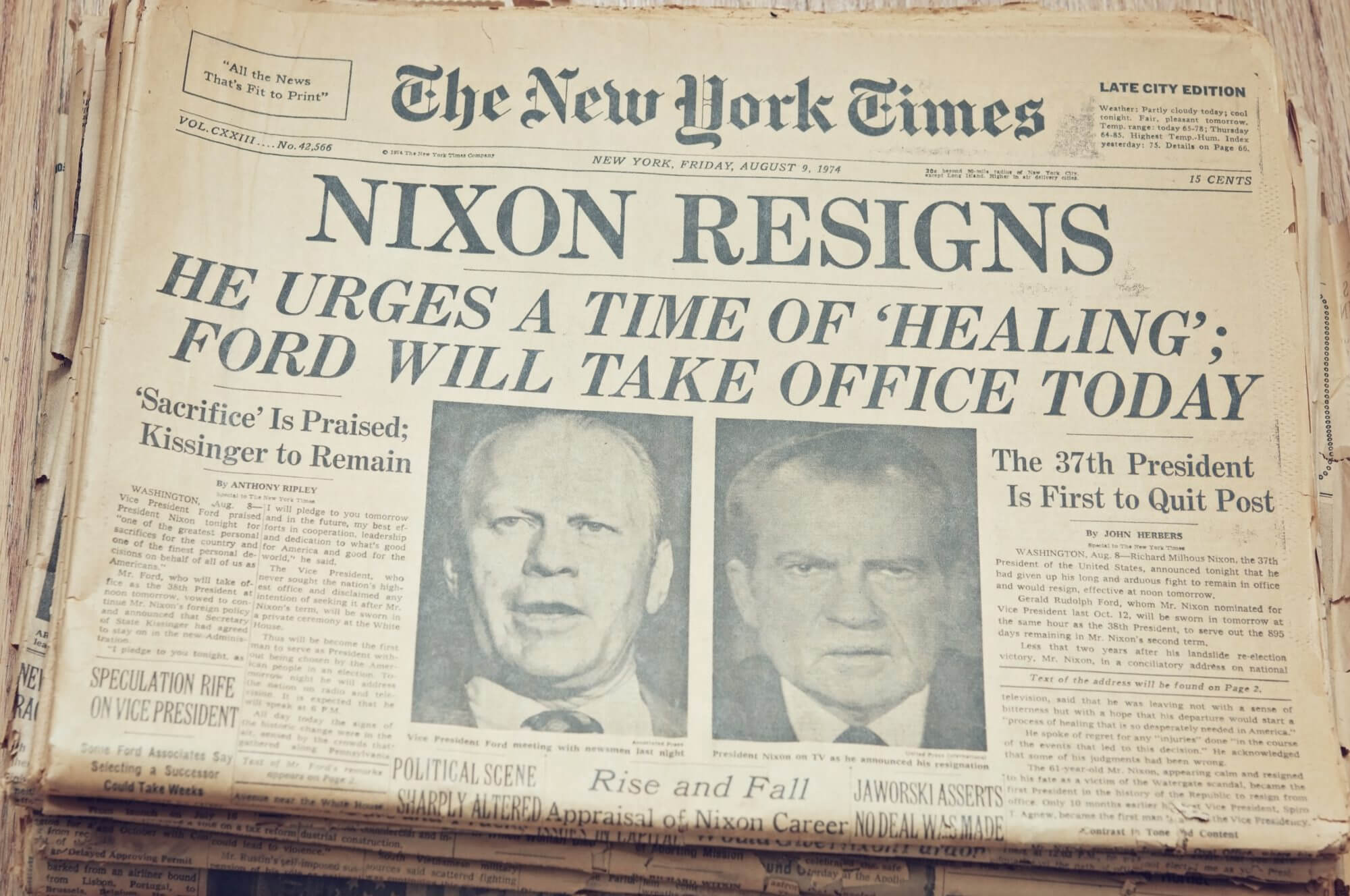

Wait. Before we get into the weeds, let's clear up the massive confusion that happens every time someone Googles this case. Most people are actually looking for United States v. Nixon (1974), the legendary Watergate tape showdown that basically forced Richard Nixon to resign. That’s not what we’re talking about here. Not even close. Nixon v. United States (1993) is a completely different beast, and honestly? It’s arguably more important for understanding how our government actually functions—or fails to—on a structural level.

This case isn't about a President. It’s about a judge. Specifically, Walter Nixon, a federal judge from Mississippi who got caught up in a bribery scandal, went to prison, and then had the absolute audacity to keep collecting his $110,000-a-year salary from behind bars because he refused to resign.

The story of how he tried to sue the entire U.S. government to keep his job is a wild ride through the "political question doctrine." It’s a wonky term, but it’s basically the Supreme Court saying, "Yeah, we’re not touching that with a ten-foot pole."

The Judge Who Wouldn't Quit

Walter Nixon was a Chief Judge for the United States District Court for the Southern District of Mississippi. In the mid-1980s, he was convicted of making false statements to a grand jury during an investigation into a drug-smuggling case involving the son of a business associate. Nixon went to federal prison.

But here’s the kicker.

Under the Constitution, federal judges have life tenure. You can’t just "fire" a federal judge like a barista who keeps burning the milk. They stay there "during good behavior." If they stop behaving, the only way to get them out is through impeachment by the House and conviction by the Senate.

Even though he was sitting in a cell, Walter Nixon refused to resign his commission. He was still technically a federal judge. He was still getting paid. To stop the bleeding, the House of Representatives impeached him in 1989. Then it went to the Senate.

👉 See also: Casey Ramirez: The Small Town Benefactor Who Smuggled 400 Pounds of Cocaine

Now, usually, you’d expect the full Senate to sit through a trial, right? Well, the Senate is busy. They didn't want to spend weeks listening to testimony about a guy who was already in prison. So, they invoked Senate Rule XI. This rule allowed a small committee of just 12 senators to hear the evidence and then report back to the full body.

Nixon hated this. He argued that the Constitution says the "Senate" shall have the sole power to "try" all impeachments. To him, "Senate" meant the whole group, and "try" meant a full-blown judicial trial. When the full Senate eventually voted to convict him based on the committee's report, Nixon sued, claiming his removal was unconstitutional.

Why the Supreme Court Said "No Thanks"

When Nixon v. United States reached the Supreme Court in 1993, the justices weren't really interested in whether Walter Nixon was a "good guy" or if the Senate was being lazy. They were looking at the separation of powers.

The Court, led by Chief Justice William Rehnquist, had to decide if they even had the authority to tell the Senate how to run an impeachment. This is where we get into the Political Question Doctrine.

Basically, the Court decided that the Constitution gives the Senate the "sole" power to try impeachments. "Sole" is a very strong word. Rehnquist argued that if the Framers wanted the Supreme Court to check the Senate’s homework on impeachments, they would have said so.

Instead, they gave the power to the legislative branch as a check on the judicial branch. If the judges could review their own colleagues' impeachments, the whole "check and balance" thing falls apart. It would be like the fox guarding the henhouse, then asking the fox to review the security footage of the henhouse.

✨ Don't miss: Lake Nyos Cameroon 1986: What Really Happened During the Silent Killer’s Release

The Nuance: Not Everyone Agreed With the Logic

While the decision was unanimous in its result (Nixon stayed fired), the reasoning was all over the place. This is the part people usually skip in law school prep.

Justice Byron White and Justice Harry Blackmun wrote a concurrence that was basically a "yes, but." They thought the Court could review impeachment proceedings if they were totally ridiculous—like if the Senate decided a conviction by a coin flip. They didn't want to give the Senate a total blank check to do whatever they wanted.

Justice David Souter had another take. He worried that if the Senate’s process was so "plainly" wrong that it threatened the very integrity of the government, the Court might have to step in. But for Walter Nixon? The committee process was "good enough."

Why This Case Is Still Making Waves Today

You might think a 30-year-old case about a corrupt judge doesn't matter in 2026. You’d be wrong. Every time a President gets impeached—which, let’s be honest, feels like a more frequent occurrence lately—Nixon v. United States is the shield the Senate uses.

When people complain that an impeachment trial isn't "fair" or doesn't follow the rules of evidence you’d see on Law & Order, this is the case lawyers point to. It established that:

- The Senate makes its own rules.

- "Try" doesn't mean a courtroom trial; it means whatever the Senate says it means.

- The Judicial branch cannot second-guess the Legislative branch on the process of impeachment.

It effectively made impeachment a "political" process rather than a strictly "legal" one. That’s a massive distinction. It means the remedy for a "bad" impeachment trial isn't a lawsuit; it’s an election.

🔗 Read more: Why Fox Has a Problem: The Identity Crisis at the Top of Cable News

The Surprising Legacy of Walter Nixon

Funny enough, Walter Nixon didn't just disappear into the shadows after losing. After getting out of prison and being stripped of his judgeship, he actually went back to practicing law in Mississippi. He’s often cited in legal circles not as a villain, but as the guy who forced the Court to define the limits of its own power.

It’s a bit ironic. A man convicted of perjury ended up being the catalyst for a Supreme Court decision that protects the independence of the Senate.

Real-World Impact: How It Affects You

Understanding this case changes how you watch the news. When you hear pundits arguing about whether an impeachment is "constitutional" because of how the hearings were handled, you can know for a fact that—legally speaking—it doesn't matter. As long as the Senate follows its own internal rules, the Supreme Court is staying out of it.

The "sole power" remains exactly that. Sole.

Actionable Insights for the Curious Citizen

If you want to go deeper into how this affects modern governance, here is what you should actually do:

- Read the actual text of Senate Rule XI. It’s surprisingly short. Seeing how a tiny rule can change the course of a constitutional crisis is eye-opening.

- Contrast this with United States v. Nixon (1974). Notice the difference? In '74, the Court stepped in because it involved evidence in a criminal trial (Executive Privilege). In '93, they stepped back because it involved the internal "business" of the Senate.

- Watch the Oral Arguments. You can find the transcripts and audio on Oyez. Listening to Rehnquist grill Nixon's lawyer about the meaning of the word "try" is a masterclass in textualism.

- Look up the Baker v. Carr criteria. This 1962 case set the six-part test for what makes something a "political question." Nixon v. United States is the textbook application of the first two prongs of that test: a "textually demonstrable constitutional commitment of the issue to a coordinate political department" and a "lack of judicially discoverable and manageable standards for resolving it."

The law isn't just a set of rules; it's a map of who is allowed to tell who what to do. Nixon v. United States drew a very thick line around the Senate chamber and told the judges to stay on their side of the street.

To fully grasp the weight of this, compare the 1993 ruling to the 1926 case Myers v. United States, which dealt with the President's power to remove executive officers. You'll see a pattern: the Court is very protective of its own turf, but very hesitant to jump into the middle of a fight between the other two branches unless it absolutely has to. Walter Nixon's $110,000 salary just wasn't worth a constitutional crisis.