It is barely a hundred pages long. You can finish it in a single sitting on a Tuesday afternoon, but you probably won't be the same person when you stand up. Night by Elie Wiesel isn't just a memoir; it’s a brutal, terrifyingly honest autopsy of the human soul under the most extreme conditions imaginable. People often categorize it as "Holocaust literature," which is true, but that label feels too sterile for what’s actually happening in these pages. It’s a book about the death of God, the death of childhood, and how a teenage boy from Sighet, Transylvania, watched his entire world vanish in the smoke of a crematorium.

I've read it several times. Each time, something different sticks. One year, it's the silence. Another year, it's the terrifying realization of how fast a "civilized" society can pivot into organized murder. Honestly, most people get it wrong when they talk about Night as a story of survival. It’s more of a story about what survives of a person when everything else—family, faith, even the basic will to live—is stripped away.

The Brutal Reality of Elie Wiesel's Sighet

Wiesel starts the book in 1941. He was just a kid, deeply religious, obsessed with the Talmud and the Kabbalah. He wanted to understand the secrets of the universe. He actually begged his father to find him a master to guide his studies. His father, a respected community leader, thought he was too young. Then came Moshe the Beadle.

Moshe is one of the most haunting figures in the book because he’s a prophet no one believes. He was deported early on, escaped a mass shooting in the woods, and came back to warn the Jews of Sighet. He told them about infants being used as target practice for machine guns. The townspeople thought he was crazy. They thought he wanted pity. It’s a chilling reminder of how humans have this built-in mechanism to reject the unthinkable. We think, "It can't happen here." But in Night, "here" was exactly where it happened.

The deportation happened in 1944. That’s late in the war. By then, the Allies were already making moves. The tragedy of the Jews in Sighet is that they were so close to the end, yet they were still sucked into the machinery of the Final Solution. The cattle cars. The lack of air. The woman, Madame Schächter, screaming about fire that no one else could see yet. When they finally arrived at Birkenau and saw the flames, they realized she wasn't crazy. She was the only one seeing clearly.

Why Night by Elie Wiesel Isn't Actually a "Diary"

There is a common misconception that Night is a diary written during the war, like Anne Frank’s. It’s not. It was written a decade later. Wiesel actually took a ten-year vow of silence about his experiences. He felt that words would only betray the truth of what happened. It wasn't until a meeting with the French author François Mauriac—who eventually wrote the foreword—that Wiesel was convinced to speak.

The original manuscript was massive. It was written in Yiddish and titled Un di Velt Hot Geshvign (And the World Remained Silent). It was nearly 900 pages. The version we read today is a highly distilled, poetic, and razor-sharp translation. Every word has been weighed. This is why the prose feels so heavy. He isn't just telling you what happened; he’s trying to make you feel the vacuum left behind.

🔗 Read more: Mike Judge Presents: Tales from the Tour Bus Explained (Simply)

The Transformation of Eliezer

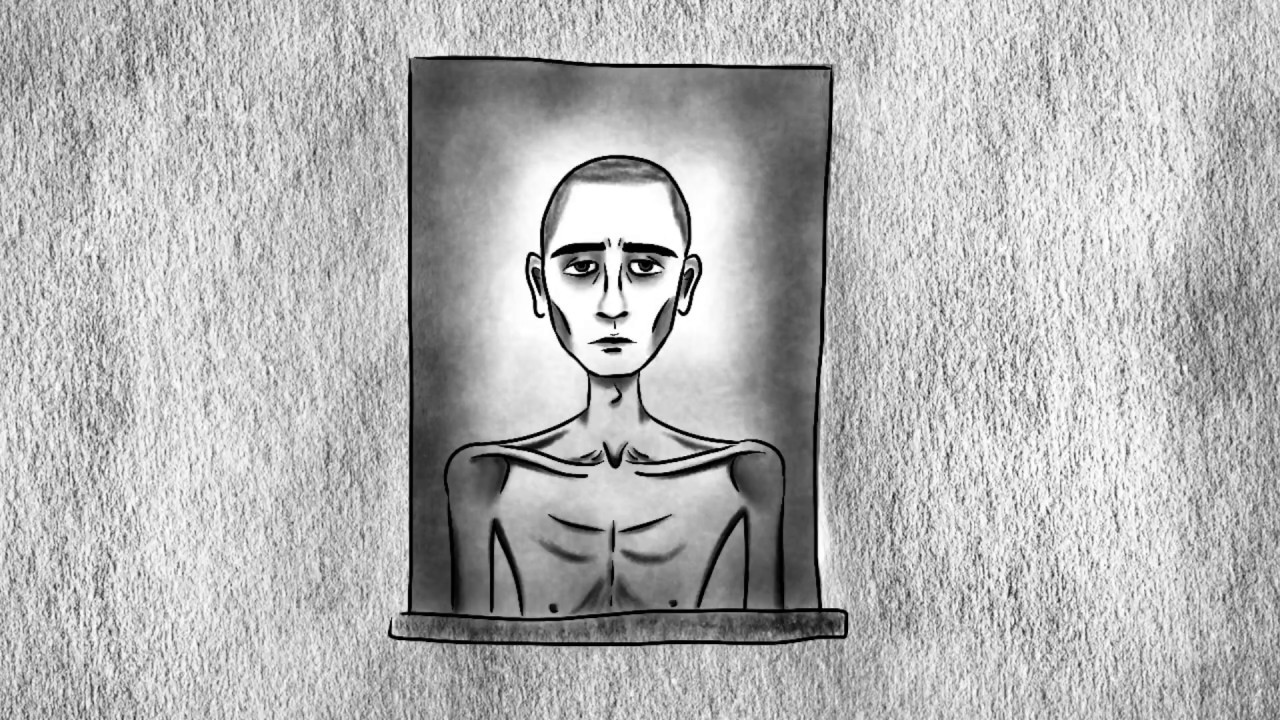

In the camps, Wiesel becomes "Eliezer." He stops being a student of mysticism and becomes a body trying to survive. One of the most famous and agonizing passages is the hanging of the "pipsal," a young boy with the face of a sad angel. Because the boy was so light, he didn't die instantly when the chair was kicked away. He struggled for half an hour.

A man behind Wiesel asked, "Where is God now?"

Wiesel’s internal response: "He is hanging here on this gallows."

That’s a pivot point. The boy who wanted to study the Kabbalah died that day. What remained was a hollowed-out version of a human being. The relationship between Eliezer and his father becomes the only tether to reality, but even that is strained by the sheer animal instinct to survive. There are moments where Eliezer resents his father for being a burden, for getting beaten, for being weak. He writes about these feelings with a guilt that is almost hard to read. It’s so raw. It’s so human.

The Controversy of Memory and Truth

Some critics and historians have picked apart the "factualness" of certain scenes in the book. It’s important to remember that Night sits in a unique space between autobiography and "testimony." Wiesel himself said that some things he saw were beyond description, so he used the tools of a novelist to convey the emotional truth.

For instance, the timeline of certain events or the exact phrasing of conversations might be shaped by the decade of reflection he had before writing. But to get bogged down in whether a specific quote happened on a Tuesday or a Wednesday misses the point of the work. The "truth" of Night is the truth of the psychological destruction of a people.

💡 You might also like: Big Brother 27 Morgan: What Really Happened Behind the Scenes

The Silence of the World

The title itself is a metaphor that covers the entire experience. Night isn't just a time of day in this book; it’s a state of being. It’s the absence of light, the absence of God, and the absence of humanity.

Wiesel was obsessed with the idea of silence.

- The silence of the victims who couldn't speak.

- The silence of the bystanders who watched.

- The silence of God in the face of absolute evil.

He eventually won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1986 because he turned that silence into a weapon against forgetting. He argued that to remain neutral is to side with the oppressor. If you read Night and feel indifferent, you’ve missed the warning.

How to Approach Night Today

If you’re picking up Night for the first time, or maybe revisiting it because it’s on a school reading list or a book club schedule, don't rush it. It's a heavy lift emotionally.

Take note of the imagery of "eyes." Wiesel spends a lot of time describing the eyes of the people he encounters—Moshe the Beadle, his father, the French girl in the warehouse, even the SS officers. Eyes are the windows to the soul, and in Night, those windows are mostly shattered or reflecting fire.

Also, look at the transition of his name. He goes from being a son and a student to being A-7713. That number was tattooed on his left arm. It’s a literal dehumanization. When he looks in the mirror at the end of the book, after the liberation of Buchenwald, he says a corpse was gazing back at him. The look in those eyes has never left him.

📖 Related: The Lil Wayne Tracklist for Tha Carter 3: What Most People Get Wrong

Key Takeaways for Understanding the Memoir

To truly grasp the impact of Night by Elie Wiesel, you have to look beyond the historical events of the 1940s and see the universal warnings it provides about human nature.

- The Danger of Normalcy: The Jews of Sighet had numerous chances to leave or hide, but their belief that "things couldn't possibly get that bad" kept them trapped. This is a recurring theme in history.

- The Fragility of Faith: Unlike many religious stories that end with a triumph of spirit, Night explores the total collapse of belief. It’s a brave admission that some horrors are too great for "everything happens for a reason" to cover.

- The Father-Son Dynamic: The book is a tragic inversion of the traditional roles. The son becomes the protector, and eventually, the one who survives by letting go. It’s heartbreaking.

- Literary Impact: Wiesel’s style—short, declarative sentences—influenced how we talk about trauma. He doesn't use flowery adjectives because the facts don't need them.

Real-World Context and Legacy

Elie Wiesel didn't just write the book and disappear. He became a global voice for human rights. He spoke out about the genocides in Rwanda, the Balkans, and Sudan. He believed that having survived the "Night," he had a moral obligation to prevent it from falling anywhere else.

His foundation, The Elie Wiesel Foundation for Humanity, continues this work. But for most of us, his legacy is that slim black book with the white lettering on the cover. It’s the book that forced the world to look into the furnace and not turn away.

Honestly, the most important thing you can do after reading it is to talk about it. Don't let the "silence" Wiesel feared take over. Whether you’re discussing it in a classroom or just thinking about it while you walk the dog, the act of remembering is the only defense we have against history repeating itself.

Actionable Steps for Deepening Your Understanding

If you want to go beyond just reading the text, here are a few ways to engage with the history and the message of the book more deeply:

- Visit a Holocaust Museum: If you're in the U.S., the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in D.C. (which Wiesel helped establish) is the gold standard. Most major cities have local centers that provide local context to survivors who immigrated there.

- Watch Wiesel’s Nobel Speech: You can find his 1986 acceptance speech online. Hearing him speak about "the perils of indifference" adds a whole new layer of gravity to the words in Night.

- Read the "Trilogy": Night is actually the first part of a trilogy. The following books, Dawn and Day, are fictional but explore the aftermath of survival and the struggle to find meaning in a world that allowed such things to happen.

- Compare Translations: If you have the older translation (usually from the 1960s), consider picking up the 2006 translation by his wife, Marion Wiesel. It’s considered more accurate to his original intent and voice.

Reading this book is a heavy experience, but it’s a necessary one. It’s a witness statement for a generation that is slowly passing away. By reading it, you become a witness too.

Next Steps:

Start by identifying the "silences" in your own environment. Wiesel’s primary message was that indifference is more dangerous than hatred. Look for areas where marginalized voices are being ignored and find small, tangible ways to amplify them. You might also consider exploring the archives at the Yad Vashem website to see the photographs and documents that correlate with the events described in Sighet and Auschwitz.