Hollywood is kinda famous for lying to us. We know this. We expect a certain amount of "creative license" when a studio decides to turn a real human life into a two-hour spectacle, but Night and Day 1946 takes that concept to a whole different level. If you sat down to watch this movie expecting a gritty, honest look at the life of legendary composer Cole Porter, you'd be deeply confused.

It’s a glossy, Technicolor daydream.

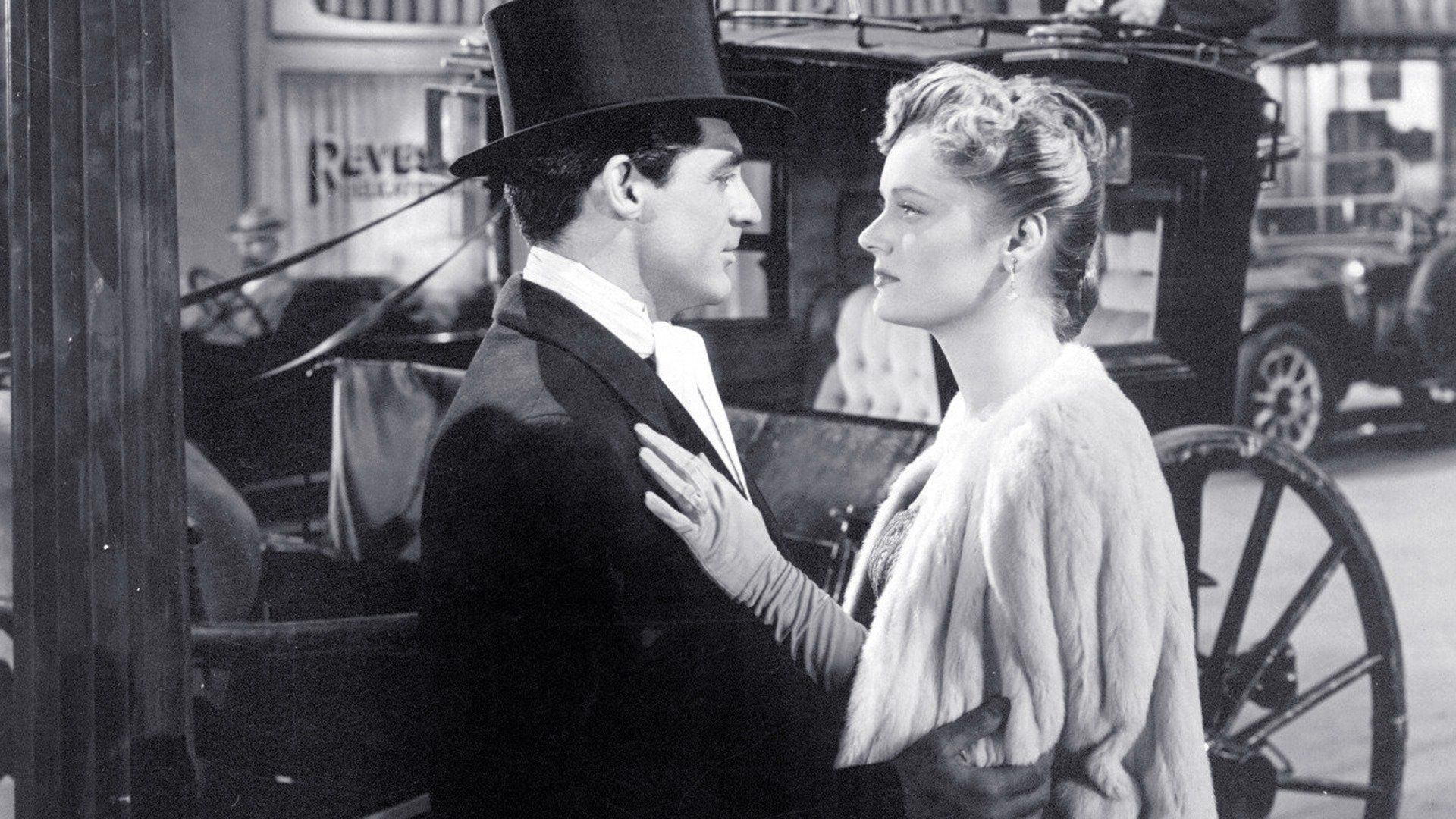

Warner Bros. released this film to celebrate their 20th anniversary of sound, and they spared no expense. They got Cary Grant—the biggest star on the planet—to play Porter. They packed the runtime with massive musical numbers. It was a huge box office hit in 1946, but looking back at it now? It feels like a transmission from an alternate universe.

The Problem With Night and Day 1946

Let’s be real: Night and Day 1946 is essentially a work of fiction that just happens to use a real person's name. It’s the "official" version of Cole Porter’s life, which means it’s the version that had to pass the strict Hays Code censors of the 1940s.

Cole Porter was a gay man. He had a complex, sophisticated, and often deeply melancholic life that was masked by his witty lyrics. But in this movie? He’s a straight-as-an-arrow war hero who falls for Linda Lee (played by Alexis Smith) in a conventional, almost sugary romance. The movie spends a lot of time on his time in the French Foreign Legion—a part of his life that Porter himself famously exaggerated or invented entirely.

It’s ironic. A man who wrote some of the most suggestive, double-entendre-laden lyrics in the Great American Songbook was given a biopic that is as sanitized as a glass of milk.

Why Cary Grant?

Cary Grant is great. He’s always great. But is he Cole Porter? Not really.

💡 You might also like: Doomsday Castle TV Show: Why Brent Sr. and His Kids Actually Built That Fortress

Grant plays the role with his signature charm and that mid-Atlantic accent that everyone loves, but he doesn't capture the specific, high-society neurosis that Porter actually possessed. Reports from the time suggest that Porter himself was actually amused by the casting. When asked what he thought about the film, he reportedly quipped that he liked it, but he wished he could have been as handsome as Cary Grant.

That tells you everything you need to know about the film's relationship with the truth. It wasn't about accuracy; it was about the brand.

The Music is the Only Truth

If you can get past the fact that the plot is basically a fairy tale, Night and Day 1946 becomes a pretty incredible concert film. That’s where the real value lies.

The production values are staggering. You get these massive, opulent stagings of "Begin the Beguine," "My Heart Belongs to Daddy," and, of course, the title track "Night and Day." These aren't just songs; they are architectural achievements of the studio system.

Monty Woolley even appears as himself. Woolley was a genuine friend of Porter’s from their days at Yale, and his presence provides the only real tether to Porter’s actual history. Seeing Woolley on screen adds a layer of "meta" commentary that the rest of the film lacks.

The film also features Mary Martin recreating her Broadway debut performance of "My Heart Belongs to Daddy." It’s an electric moment. For a few minutes, the artifice of the biopic drops away, and you’re just watching a master at work.

📖 Related: Don’t Forget Me Little Bessie: Why James Lee Burke’s New Novel Still Matters

The Accident

The movie does tackle one real, tragic event: Porter’s 1937 horse-riding accident.

In real life, both of Porter’s legs were crushed when a horse fell on him. He spent the rest of his life in excruciating pain, undergoing dozens of surgeries, and eventually having his right leg amputated. It’s a dark, heavy story.

In Night and Day 1946, the accident is treated with a bit more "movie magic" gravitas. While it shows the struggle, it mostly uses the injury as a plot device to bring his wife, Linda, back to his side. It minimizes the decades of phantom pain and depression that defined Porter’s later years. By glossing over the severity of his physical trauma, the film misses the most heroic part of Porter’s life: the fact that he kept writing some of the world's most joyful music while living in a state of constant physical agony.

A Product of Its Time

You have to look at 1946 to understand why this movie looks the way it does. World War II had just ended. The American public didn't want a psychological character study of a tortured artist. They wanted glamour. They wanted Cary Grant in a tuxedo. They wanted to hear songs they already knew the words to.

Warner Bros. was also in a bit of a "prestige" war with other studios like MGM. They wanted to prove they could do the "Big Musical" better than anyone else.

This resulted in a movie that is beautiful to look at but hollow to inhabit. The Technicolor is vibrant—almost aggressively so. The costumes are immaculate. The sets are gargantuan. It’s a triumph of art direction and a failure of biography.

👉 See also: Donnalou Stevens Older Ladies: Why This Viral Anthem Still Hits Different

Comparing Night and Day to De-Lovely

If you want to see how much the world changed, compare Night and Day 1946 to the 2004 biopic De-Lovely starring Kevin Kline.

De-Lovely actually deals with Porter’s sexuality. It deals with the "arrangement" of his marriage. It deals with the bitterness and the darkness. Most modern critics prefer De-Lovely because it feels more "honest," but there’s something fascinating about the 1946 version.

There is a strange, haunting quality to watching a film where the subject was still alive during production (Porter died in 1964) and essentially watched a fictionalized, "perfected" version of himself being projected onto the screen. It’s the ultimate 1940s PR move.

How to Watch It Today

If you decide to seek out Night and Day 1946, go into it with your eyes open.

- Don't treat it as history. If you want the real story, read Cole Porter: A Biography by Charles Schwartz or William McBrien’s work.

- Watch it for the craft. The cinematography by Peverell Marley and William V. Skall is a masterclass in the three-strip Technicolor process.

- Listen to the arrangements. While some of the orchestrations are a bit "symphonic" for modern tastes, they represent the peak of the Hollywood studio orchestra.

The film serves as a time capsule. It shows us what Hollywood thought a "great man" should look like in the mid-40s. He should be stoic, he should be married to a beautiful woman who supports him, and he should never have a problem that a big musical number can't eventually solve.

Actionable Takeaways for Movie Buffs

If you’re a fan of the Great American Songbook or classic cinema, here is how to actually engage with this film:

- Compare the "My Heart Belongs to Daddy" sequences. Watch Mary Martin in this film and then look for footage of the original Broadway staging if available. The 1946 version is a fascinating example of how Broadway was "translated" for a mass cinema audience.

- Look at the credits. Notice the names involved. Michael Curtiz directed this. This is the same guy who directed Casablanca. Seeing how he applies his visual style to a musical is a trip for any film nerd.

- Contextualize the "Legion" scenes. Research Porter's actual claims about the French Foreign Legion. He used to tell people he joined to fight in WWI, but records suggest he mostly just hung out in Paris throwing parties. The fact that the movie treats his "service" as 100% factual is a hilarious nod to Porter's own penchant for myth-making.

- Identify the "Standards". Use the film as a gateway to Porter’s discography. While the movie might be "meh," the songs are permanent. Listen to recordings by Ella Fitzgerald or Frank Sinatra after watching the film to hear how these songs were meant to be interpreted without the 1940s orchestral "bloat."

Night and Day 1946 isn't a good biography, but it’s a fascinating piece of cultural history. It’s the story of how a man who lived a very "modern" and complicated life was squeezed into a traditional, conservative box for the sake of mass entertainment. It’s a movie that tells us very little about Cole Porter, but an awful lot about the world he lived in.