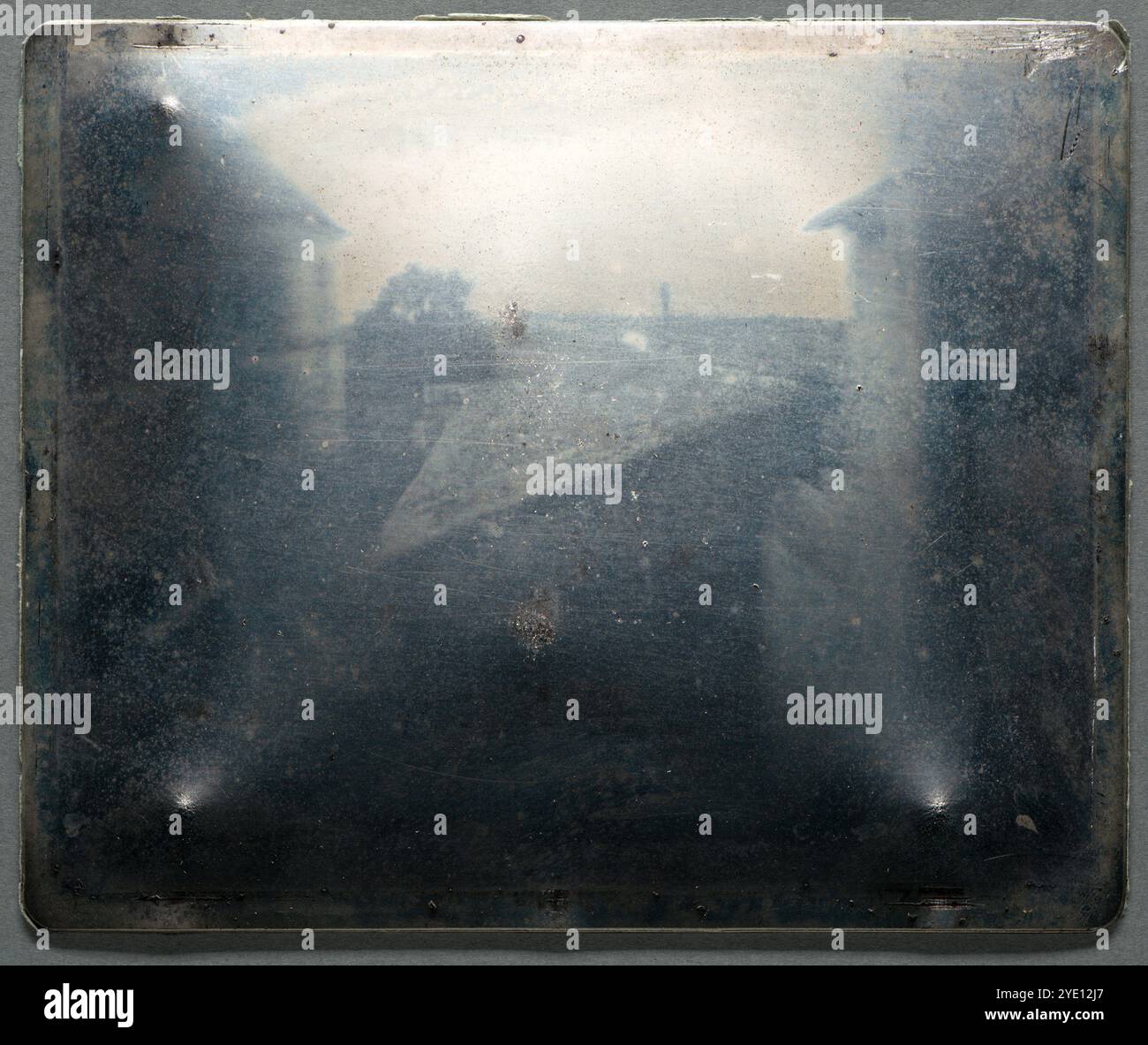

Honestly, if you saw it in person without knowing what it was, you’d probably think it was a dirty piece of scrap metal. It’s faint. It’s blurry. It’s a 200-year-old smudge on a pewter plate that looks like someone spilled grease on a baking sheet.

But this is it. This is the "big bang" of every selfie, war photo, and grainy Bigfoot sighting ever recorded.

Joseph Nicéphore Niépce didn't call it a photograph. He called it a heliograph—literally "sun writing." When he leaned out of his workroom window at his family estate, Le Gras, in Saint-Loup-de-Varennes back in 1826 (or maybe 1827, historians still bicker over the exact month), he wasn't trying to change the world. He was just a guy who was really bad at drawing and wanted a shortcut.

The "Eight Hour" Myth and the Reality of Le Gras

If you've ever taken a History of Photography 101 class, you probably heard the same "fact" I did: the exposure took eight hours.

That's actually a bit of a simplification.

Sure, the sun moved across the sky during the exposure, which is why the buildings in the image appear to be lit from both sides at once. It creates this eerie, dreamlike lighting that shouldn't exist in nature. But recent research, including studies from the Getty Conservation Institute, suggests that eight hours might have been a best-case scenario.

In reality? It could have taken several days.

Imagine leaving a camera open for three days just to get a blurry shot of your backyard. That’s the level of patience we’re talking about. Niépce wasn't using film or digital sensors; he was using bitumen of Judea—essentially naturally occurring asphalt—dissolved in lavender oil.

How the Magic Actually Happened

- The Plate: He took a polished pewter plate (an alloy of tin, lead, and copper).

- The Goop: He coated it in that bitumen mixture.

- The Light: He stuck it in a camera obscura.

- The Hardening: Light makes bitumen harden. The parts of the plate hit by the "bright" areas of the courtyard became solid, while the "shadow" areas stayed soft and soluble.

- The Wash: He rinsed the plate with more lavender oil and petroleum. The soft bits washed away, revealing the dark metal underneath.

The result? Niepce View from the Window at Le Gras. It’s a direct positive. There’s no negative. There’s no way to make copies. It’s a one-of-a-kind artifact that almost vanished from history.

The 50-Year Disappearance

For a long time, the world totally forgot this thing existed.

After Niépce died in 1833, his partner Louis Daguerre took the spotlight (and the credit) with the Daguerreotype. Niépce’s original plate ended up in the hands of a British botanist named Francis Bauer. Then it bounced around through a chain of private owners.

By the early 1900s, it was "lost."

It wasn't until 1952 that historian Helmut Gernsheim tracked it down. He found it in an old trunk in London, tucked away in a warehouse. When he first looked at it, he couldn't see anything. He had to tilt the plate at just the right angle under a strong light before the ghostly image of the Le Gras courtyard finally appeared.

Even then, the "famous" version of the photo you see in textbooks isn't what the plate looks like. That high-contrast, black-and-white image was actually a reproduction made by the Kodak Research Laboratory in 1952. They spent days trying to "re-photograph" the plate to make it legible for the public.

2026: The 200th Anniversary

Right now, in 2026, we’re hitting a massive milestone. France has declared this the Bicentenary of Photography.

There are huge exhibitions happening at the Grand Palais in Paris and the Nicéphore Niépce Museum in Chalon-sur-Saône. It’s a weird time to look back at this piece of tech. We’re currently obsessed with Generative AI and whether a photo is even "real" anymore, yet we’re looking back at a piece of metal that required three days of sun just to prove that a barn existed.

✨ Don't miss: Why 3D printing in the automotive industry is finally moving past the hype

If you want to see the original, you have to go to the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin.

It’s housed in a high-tech, oxygen-free steel case filled with an inert gas. They keep the lights low because, ironically, the very thing that created the image—light—is now its greatest enemy. If you stand in the lobby there, you’ll notice people squinting at a dark mirror. That’s the "view." It’s subtle.

What You're Actually Looking At

It’s hard to orient yourself when looking at the plate, so here’s the layout of that 1826 backyard:

- Left side: A turret-like pigeon house (the "upper loft").

- Middle: A pear tree (mostly just a fuzzy blob now).

- Right side: The slanting roof of the barn and a long roof with a low chimney.

Why Should You Care?

It’s easy to dismiss this as a "boomer" version of technology, but Niépce was basically the first person to "hack" reality. Before him, if you wanted to see a place, you had to go there or trust a painter.

He found a way to let the sun do the work.

He called it "the first uncertain step in a completely new direction." He was right. Without that blurry pewter plate, we don't get cinema, we don't get the moon landing photos, and we certainly don't get Instagram.

Actionable Insights: How to Experience Le Gras Today

If you're a photography nerd or just a history buff, don't just look at the Wikipedia thumbnail.

- Visit the Source: If you can get to Austin, Texas, the Harry Ransom Center is free. But check their "on view" status first; they occasionally take it off display for conservation checks.

- Digital Deep Dive: The Ransom Center has a dedicated "First Photograph" site with a "Plate Study" tool. You can toggle between the original unretouched plate and the Kodak enhancement. It’s the best way to understand how faint the original actually is.

- The French Connection: If you’re in Europe, head to Saint-Loup-de-Varennes. The house is a museum now. They’ve actually used laser measurements to figure out the exact window Niépce used. Interestingly, they discovered the window was moved about 70 centimeters during a later renovation, which confused historians for years.

The Niepce View from the Window at Le Gras is a reminder that every revolution starts with a mess. It wasn't perfect, it wasn't fast, and it barely worked. But it stayed.

Go see the plate or explore the new 2026 digital archives. Understanding where the "click" started makes every photo you take today feel a little bit more like a miracle.

Next Steps for You

- Check the Harry Ransom Center’s digital gallery: They’ve uploaded new, ultra-high-res scans for the 2026 bicentenary that show the texture of the bitumen.

- Research "The Cardinal": This was Niépce’s other famous heliograph (an engraving reproduction). It shows he was thinking about "copying" art long before he was "taking" photos.

- Compare with Daguerre: Look up the "Boulevard du Temple" (1838) to see how much the tech jumped in just 12 years.