Everyone knows the name Marco Polo. It’s a pool game, a fashion brand, and the default name for "explorer" in our collective brain. But here’s the thing: Marco wasn't the first in his family to bridge the gap between Europe and the Mongol Empire. Not even close. Before Marco was even old enough to hold a quill, his father, Niccolo Polo, and his uncle, Maffeo Polo, had already crossed the world.

Honestly, it's kinda wild how they've been pushed into the background of history. Without Niccolo and Maffeo, Marco would have just been another Venetian merchant kid selling fabric in a lagoon. Instead, these two brothers spent years wandering through parts of the world that Europeans didn't even believe existed.

The Great Escape from Constantinople

It started in 1260. Venice was a powerhouse, and the Polo brothers were essentially high-stakes venture capitalists of the Middle Ages. They weren't just "travelers"—they were jewel merchants. They lived in the Venetian quarter of Constantinople, but they had a weirdly good gut feeling that the city was about to fall.

They were right.

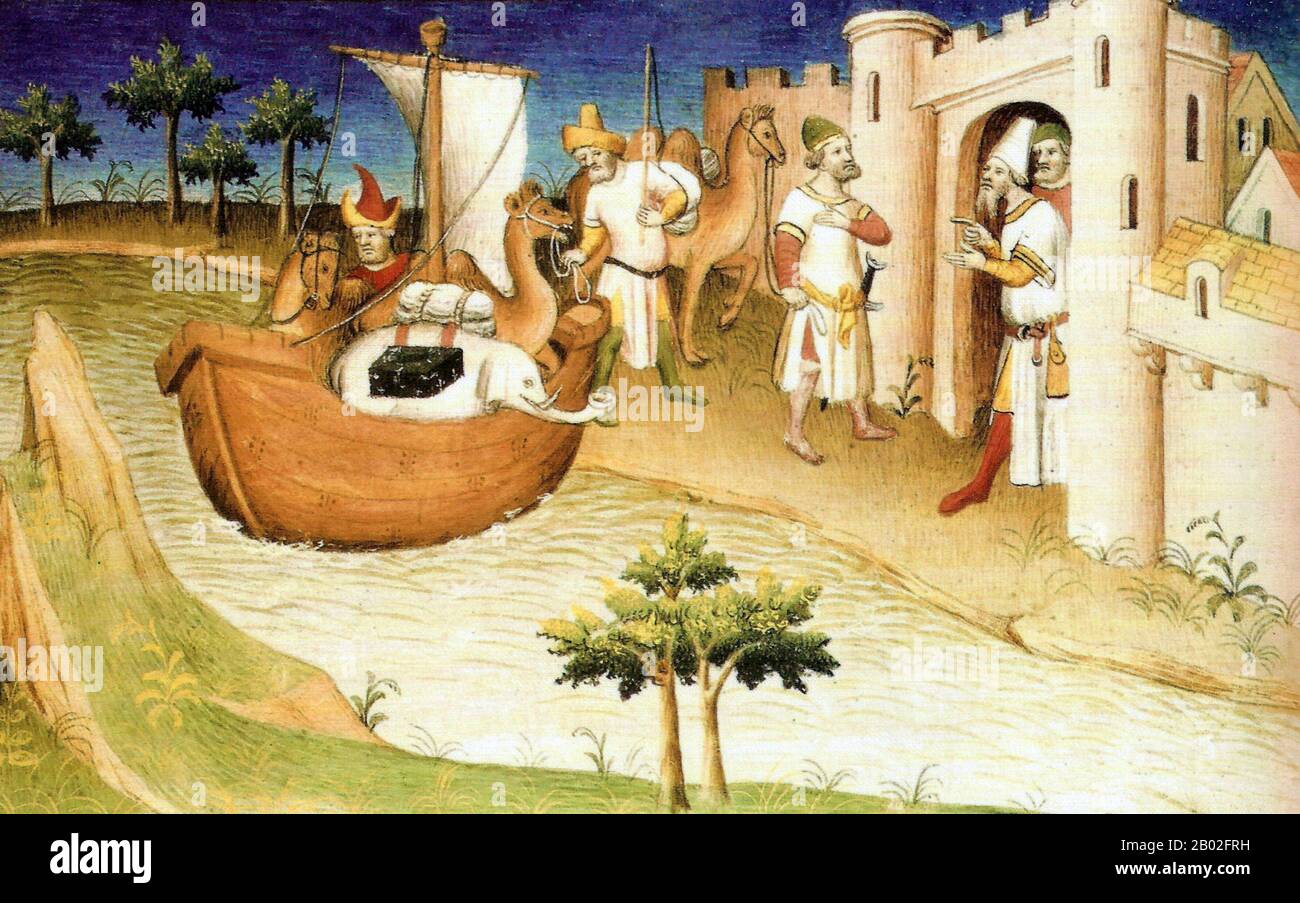

Just before the Byzantines retook the city in 1261, Niccolo and Maffeo liquidated everything. They turned their assets into portable wealth—mostly jewels— and headed for the Black Sea. They didn't intend to find a new world; they were just looking for a better market.

Eventually, they ended up in Sudak, Crimea. Then things got complicated. War broke out between local Mongol leaders (Berke Khan and Hulagu), and the road back home was suddenly blocked. Basically, they were stuck in the middle of the Mongol Empire with nowhere to go but further east.

The First Meeting with Kublai Khan

Most people think Marco Polo discovered the Silk Road, but Niccolo and Maffeo Polo reached the court of Kublai Khan a full decade before Marco ever saw China.

📖 Related: Bryce Canyon National Park: What People Actually Get Wrong About the Hoodoos

Imagine being the first Westerners to walk into the court of the most powerful man on Earth. Kublai Khan was the grandson of Genghis, and he was fascinated by these two Italians. He had never met Europeans before. He didn't just want their jewels; he wanted their brains. He grilled them on everything: how did the Pope work? What were the kings of Europe like? How did Christianity function?

Kublai was so impressed that he turned them into his personal ambassadors. This is the part history books usually skip. He sent them back to Europe with a massive request. He wanted the Pope to send 100 educated men—priests and scholars—to teach his people about Western religion and science.

He also gave them a paiza. This was a golden tablet that acted like a medieval diplomatic passport. If you had a paiza, you could get free horses, food, and lodging anywhere in the Mongol Empire. It was the ultimate "access all areas" pass.

Why the Second Trip Changed Everything

When they finally made it back to Venice in 1269, Niccolo found out his wife had died. He also met his fifteen-year-old son, Marco, for the first time.

You've gotta wonder what that first conversation was like. "Hey kid, I know I've been gone for nine years, but do you want to walk across the Gobi Desert?"

The brothers tried to fulfill the Khan's request for 100 priests, but the Catholic Church was in the middle of a three-year "sede vacante"—basically, there was no Pope. When Pope Gregory X was finally elected, he only gave them two friars. Those friars? They took one look at the rugged mountains of Armenia and turned around. They quit.

👉 See also: Getting to Burning Man: What You Actually Need to Know About the Journey

But Niccolo and Maffeo didn't. They took young Marco and kept going.

The Legend of the Siege Engines

There is a specific detail in the historical accounts that makes these guys sound like actual action heroes. During the siege of Saianfu (Xiangyang), the Mongol army was stuck. They couldn't break the city walls.

According to some versions of The Travels, Niccolo and Maffeo stepped up as military consultants. They allegedly helped design massive catapults—mangonels—capable of throwing 300-pound stones. Whether they actually built them or just supervised the engineers is debated by historians, but it shows the level of trust the Khan had in them. They weren't just guests; they were assets.

What Most People Get Wrong

The biggest misconception is that the Polos were just "tourists" or "explorers."

In reality, they were "ortoq"—merchant partners of the Mongols. They were part of a specific financial system where they traded using capital provided by the Mongol elite. It was a sophisticated, high-level business arrangement.

Also, we often forget that Niccolo and Maffeo spent roughly 24 years in Asia. They didn't just "visit" China; they lived there. They became part of the machinery of the Yuan Dynasty. When they finally left in 1292, it wasn't because they were bored. It was because Kublai Khan was getting old, and they knew that once he died, they’d lose their protection.

✨ Don't miss: Tiempo en East Hampton NY: What the Forecast Won't Tell You About Your Trip

They returned to Venice in 1295, stitched jewels into the hems of their coats to hide their wealth, and arrived home looking like beggars. Their own family didn't recognize them.

Actionable Insights: Lessons from the Polo Brothers

Even in 2026, the way Niccolo and Maffeo navigated the world offers some pretty solid takeaways:

- Risk Mitigation is Key: They left Constantinople right before it fell. Knowing when to "liquidate" and move is as important now as it was in 1260.

- Cultural Intelligence Wins: They didn't try to change the Mongols; they learned to speak their language and respect their customs. In any international venture, adaptability is your best currency.

- The Power of Official Credibility: That golden tablet (paiza) reminds us that having the right "credentials" or "networks" opens doors that money alone can't.

- Persistence Over Perfection: They didn't get the 100 priests the Khan asked for. They only had some holy oil and a few letters. But they showed up anyway. Sometimes, showing up is 90% of the battle.

If you want to understand the true origins of East-West relations, stop looking at Marco and start looking at his father. Niccolo and Maffeo Polo didn't just follow a path; they built it. They were the ones who proved that the world was much, much bigger than the Mediterranean.

Next time you hear someone mention Marco Polo, remember that he was just a teenager following the lead of two men who had already survived the impossible.

For those looking to dive deeper, I'd suggest checking out the modern translations of The Travels of Marco Polo, but keep a specific eye on the prologue—that's where the real story of the brothers is buried. Focus on the early chapters covering the years 1260 to 1269; that's where the blueprint for the entire Silk Road era was drafted.