Math and football don't always mix well. If you’ve ever looked at a box score and wondered why a guy with three touchdowns has a lower "rating" than a guy with one, you aren't alone. It’s a mess. Honestly, the formula for quarterback rating—officially known as the NFL Passer Rating—is one of the most misunderstood equations in professional sports. People call it "QB Rating," but the NFL is very picky about calling it "Passer Rating" because it doesn't account for rushing, fumbles, or leadership. It’s just about the arm.

Since 1973, this specific mathematical beast has determined who leads the league and who gets a massive contract extension. It wasn't handed down by gods. A committee led by Don Smith of the Pro Football Hall of Fame actually sat down and built this thing to create a standardized way to compare eras. They wanted a system where 66.7 was average and 100 was "great." Back then, nobody was throwing for 5,000 yards. Now? If a starter has a 66.7 rating, he’s probably getting benched by halftime.

The Four Pillars of the Formula for Quarterback Rating

The first thing you need to realize is that the NFL doesn't just do one long math problem. It’s actually four separate mini-calculations that get smashed together at the end. You’re looking at completion percentage, yards per attempt, touchdowns per attempt, and interceptions per attempt. That’s it. There is no "clutch factor" or "third-down conversion" metric hidden in here.

To calculate it yourself, you have to find four variables:

- Completion Percentage Component: You take the completions divided by attempts, subtract 0.3, and then multiply by 5.

- Yards Per Attempt Component: Take yards divided by attempts, subtract 3, and multiply by 0.25.

- Touchdown Component: Take touchdowns divided by attempts and multiply by 20.

- Interception Component: This one is a bit negative. You take 2.375 and subtract the result of (interceptions divided by attempts multiplied by 25).

If that sounds like a headache, it’s because it is. But there’s a catch. Each of these four results cannot be higher than 2.375 or lower than zero. If a quarterback is playing out of his mind and his "yards per attempt" math comes out to 2.8, the league just caps it at 2.375. This is why you can’t have a passer rating of 500. The maximum possible score is 158.3.

Wait. 158.3? Why such a random number?

Basically, if you max out all four categories at 2.375, you add them up ($2.375 + 2.375 + 2.375 + 2.375 = 9.5$), divide by 6, and multiply by 100. That gives you 158.333... which the NFL rounds down. It’s arbitrary. It’s weird. But it’s the law of the land.

Why the "Perfect" Game is Kinda Misleading

You’ve probably heard an announcer scream about a "perfect passer rating." It sounds like the QB played a flawless game. But they didn't have to. Because of those caps I mentioned—the 2.375 limit—a quarterback can actually throw an incomplete pass and still finish with a 158.3.

✨ Don't miss: Top 5 Wide Receivers in NFL: What Most People Get Wrong

Take a look at Craig Morton. In 1981, he had a "perfect" game. He went 17 for 18. That one incompletion didn't matter because his other stats were high enough to hit the 2.375 ceiling in every category. It’s a bit like a "ceiling" in a house; once you hit it, it doesn't matter if you have a ladder or a rocket ship. You're still at the ceiling.

This is where the formula for quarterback rating starts to show its age. It weighs completion percentage very heavily. If a quarterback throws 40 check-downs for 3 yards each, his rating might look better than a guy who takes risks and throws 20-yard strikes but misses a few more targets. It rewards efficiency over aggression. This is why guys like Kirk Cousins often have career ratings that rival first-ballot Hall of Famers. Efficiency is the "cheat code" for this specific math.

The Problem with Sacks and Rushing

The biggest gripe experts have with the NFL's math is what it leaves out. If a quarterback holds onto the ball too long and gets sacked 10 times, his passer rating doesn't move. Not a single point. He could lose 80 yards on those sacks, and the formula treats him like he never stepped on the field for those plays.

Then there’s the Lamar Jackson or Josh Allen factor. These guys are weapons on the ground. However, the passer rating formula treats a 50-yard touchdown run exactly the same as if the quarterback sat on the bench. It ignores it. In the modern NFL, where the "dual-threat" is the gold standard, the traditional formula for quarterback rating feels a bit like using a map from 1750 to navigate New York City. It gets the general shape right, but you're going to miss a lot of important turns.

How College Football Does it Differently

If you think the NFL's 158.3 is confusing, don't look at the NCAA. They use a completely different version of the formula for quarterback rating. The college version doesn't have a cap. It’s why you’ll see a college quarterback with a rating of 210.4.

The college formula is simpler: $((8.4 \times \text{Yards}) + (330 \times \text{Touchdowns}) - (200 \times \text{Interceptions}) + (100 \times \text{Completions})) / \text{Attempts}$.

It’s a more linear way of looking at it, but it makes it impossible to compare a Saturday afternoon performance to a Sunday night game. If the NFL used the college formula, Joe Burrow’s record-breaking seasons would look like something out of a video game. The NFL sticks to its 1973 roots mostly because of historical record-keeping. They want to be able to compare Patrick Mahomes to Roger Staubach, even if the game looks nothing like it did 50 years ago.

🔗 Read more: Tonya Johnson: The Real Story Behind Saquon Barkley's Mom and His NFL Journey

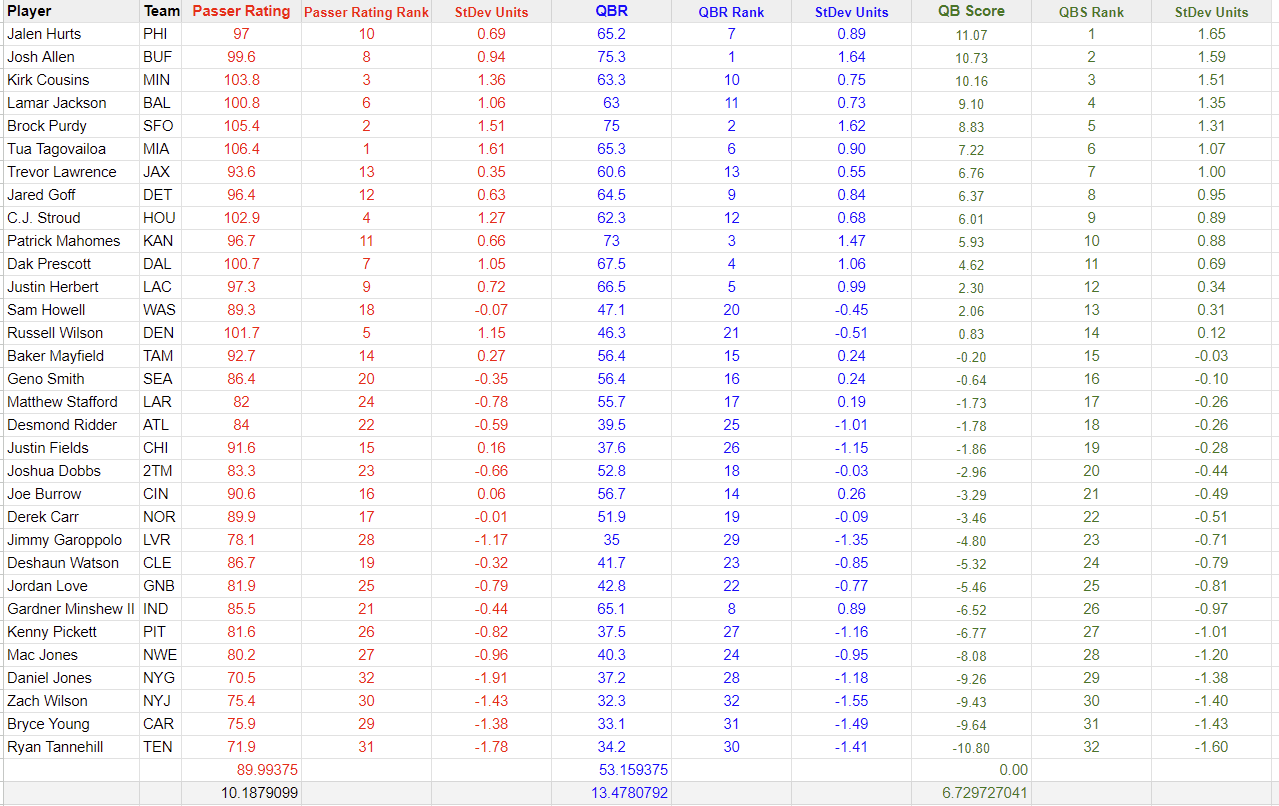

Total QBR: The ESPN Alternative

Because the traditional formula is so flawed, ESPN came out with "Total QBR" around 2011. They tried to fix everything. They added rushing yards, they added sacks, and they even tried to account for "clutch time." If you throw a touchdown when you're up by 30 points, QBR says it’s worth less than a touchdown when you're down by 4 with a minute left.

The problem? Nobody actually knows exactly how QBR is calculated. It’s a proprietary "black box" algorithm. While the NFL's formula for quarterback rating is public—anyone with a calculator and a 5th-grade education can do it—QBR is a secret. This makes fans skeptical. We like to see the work. Even if the old formula is a bit dusty, at least we know why a QB got a 92.4.

Does it actually matter for winning?

Statistically, yes. Despite its flaws, passer rating is still one of the best predictors of winning. If a team has a higher passer rating than their opponent in a single game, they win about 80% of the time. It’s a better predictor than rushing yards or total yards.

Why? Because it measures the avoidance of disasters (interceptions) and the presence of big plays (touchdowns and yards per attempt). A high rating means you aren't killing your team with turnovers and you’re moving the ball downfield. That’s the core of winning football, regardless of what era you’re in.

Calculating Your Own: A Practical Example

Let’s say you’re watching a game and the QB goes 20 for 30, for 250 yards, 2 touchdowns, and 1 interception.

- Completion %: $20/30 = 0.666$. $(0.666 - 0.3) \times 5 = 1.833$.

- Yards/Attempt: $250/30 = 8.33$. $(8.33 - 3) \times 0.25 = 1.333$.

- TD %: $2/30 = 0.066$. $0.066 \times 20 = 1.333$.

- INT %: $1/30 = 0.033$. $2.375 - (0.033 \times 25) = 1.55$.

Add those up: $1.833 + 1.333 + 1.333 + 1.55 = 6.049$.

Divide by 6: $1.008$.

Multiply by 100: 100.8.

That’s a solid day at the office. If that interception hadn't happened, the rating would have jumped to nearly 115. One mistake carries a massive weight in this formula, which is why "game managers" who never throw picks often end up with higher ratings than gunslingers who throw for 400 yards but toss two interceptions.

💡 You might also like: Tom Brady Throwing Motion: What Most People Get Wrong

Surprising Records and Statistical Anomalies

Did you know that the "perfect" game has happened less than 100 times in the history of the league? It’s rare. But what’s weirder is the "zero" rating. To get a 0.0, you have to be spectacularly bad. You need no touchdowns, a completion percentage under 30%, and a bunch of interceptions.

Rex Grossman famously had a 0.0 rating in a game where he actually won. The Chicago Bears defense was so good they carried him to a victory despite his stats being mathematically equivalent to a trash can. It highlights the biggest flaw: passer rating is a person's stat, but football is a team game. A QB gets a high rating if his receiver makes a crazy one-handed catch and runs for 80 yards. The QB gets the "yards" credit for the formula, even if he only threw the ball two feet.

How to Use This Information

Next time you're arguing with your friends at a bar or on a Discord server, don't just cite the rating. Look at the "Yards Per Attempt" (YPA). Most pro scouts believe YPA is the "secret sauce" inside the formula for quarterback rating. A high rating with a low YPA usually means a quarterback is being "carried" by a system of short, easy passes. A high rating with a high YPA means you’re looking at a superstar.

Also, keep an eye on the "Interception Rate." Because the formula penalizes picks so heavily, a quarterback who is "safe" will always look better than he actually is. If you want to find the real value, look at the rating in conjunction with "Sack Rate." If a guy has a 105 rating but gets sacked 6 times a game, he’s killing the offense in ways the formula is too blind to see.

To get the most out of these stats, start tracking "Adjusted Net Yards Per Passing Attempt" (ANY/A). It’s basically the passer rating formula but it actually counts sacks and weights touchdowns/interceptions more realistically. It’s the "nerd" version of the stat, but it’s much more accurate for predicting who will actually make it to the Super Bowl.

Stop treating the 158.3 as a holy grail. It’s just a 50-year-old math project that we’ve all agreed to keep using because we’re used to it. It gives you a snapshot, but it’s never the whole movie. Look for the outliers, check the rushing stats, and remember that sometimes, a 0.0 rating still gets you a win.