You’re sitting at a table in a cafe on Main Street, Newark, watching the sky turn that weird, bruised shade of purple. You pull up a weather app. It shows a massive green and yellow blob heading right for the University of Delaware campus. But here’s the thing: that "live" image isn't actually coming from a tower in Newark.

It’s a bit of a local secret, or at least a technical quirk, that there is no National Weather Service (NWS) radar site physically located within Newark city limits.

💡 You might also like: How to Use the Firestick Without Pulling Your Hair Out

Honestly, most people assume the radar is just "there," somewhere in the background. In reality, Newark sits in a bit of a cross-border radar handoff zone. To get the most accurate Newark DE doppler radar data, your phone is actually talking to a giant spinning dish about 40 miles away in New Jersey or a military site down in Dover.

Where the Data Actually Comes From

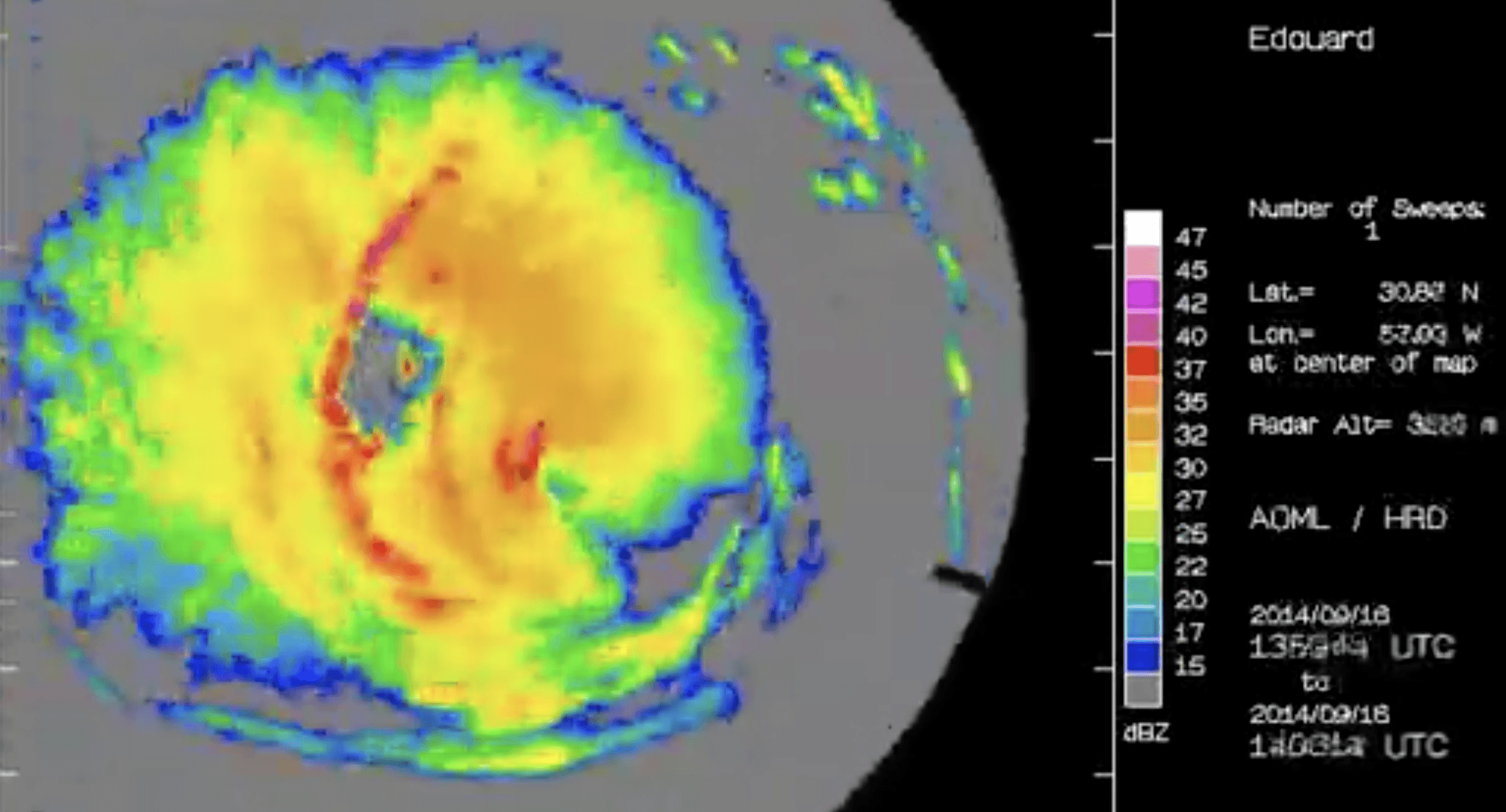

When you search for Newark DE doppler radar, you are almost certainly looking at data from KDIX. That is the official NWS Nexrad station located at Fort Dix/Mount Holly, New Jersey.

It’s the workhorse for the entire Philadelphia metro area, including New Castle County. Because Newark is on the western edge of KDIX’s primary coverage, the beam has to travel quite a distance. By the time the radar pulse reaches the Christiana Mall or the UD reservoir, it’s already thousands of feet up in the air. This matters. If a storm is "shallow"—like a low-level snow band or a small, spin-up tornado—the New Jersey radar might overshoot it entirely.

To fill that gap, meteorologists often flip over to KDOX. That’s the radar station at Dover Air Force Base. It’s closer to Newark than some of the Pennsylvania stations, and it provides a much better look at weather moving up from the Delmarva Peninsula.

Why Your App Might Be Lying to You

Have you ever noticed that "ghost rain" on your screen? You see green pixels over Newark, but you walk outside and it’s bone dry.

This is a common technical glitch called virga. The Newark DE doppler radar is catching moisture high in the atmosphere, but the air near the ground is so dry that the rain evaporates before it hits the sidewalk on Delaware Ave. Because the KDIX beam is so high by the time it gets to us, it sees the rain at 5,000 feet and assumes it's hitting your head. It isn't.

Then there is the "Cone of Silence." This isn't a spy movie thing; it's a physical limitation of the radar. Radars can't scan directly above themselves. Since Newark is far enough from both Mount Holly and Dover, we don't have to worry about the cone, but we do have to deal with beam broadening. The further the signal travels, the wider it gets, sort of like a flashlight beam. This makes the images of storms over Newark look a little "fuzzier" than they do over Philadelphia or Dover.

The Best Ways to Track Newark Weather

If you want the "pro" experience instead of just the basic app that comes on your phone, you've gotta change your sources.

- RadarScope: This is what the chase-geeks and meteorologists use. It costs a few bucks, but it lets you look at "Base Reflectivity" and "Velocity." If you want to see if a storm over Brookside is actually rotating, this is the tool.

- NWS Mount Holly (PHI): This is the local office responsible for Newark. Their Twitter (X) feed is often faster than any app because they have humans interpreting the Newark DE doppler radar in real-time.

- The Terminal Doppler Weather Radar (TDWR): These are specialized radars for airports. While Newark doesn't have one, the one serving Philadelphia International (PHL) often catches low-level wind shear that the big NWS radars miss.

Real Talk on Accuracy

Weather in Northern Delaware is notoriously tricky. We are stuck between the Appalachian foothills and the Atlantic Ocean. This creates a "micro-climate" where it might be dumping snow at the Newark Reservoir while it's just a cold drizzle at the Wilmington Riverfront.

Standard Newark DE doppler radar sometimes struggles with this transition. During winter storms, the radar might show "pink" (meaning a mix of rain and snow), but the actual temperature profile over Newark can change in a matter of blocks.

If you're trying to figure out if you actually need to shovel the driveway, don't just look at the colors on the map. Look at the Correlation Coefficient (CC) if your app allows it. This is a specific radar product that helps distinguish between "round" things (raindrops) and "irregular" things (snowflakes or sleet).

✨ Don't miss: Backward phone number lookup free: Why it’s harder than it used to be

How to Read the Radar Like a Local

- West to East is the Rule: Most of our heavy hitters come from Maryland or Pennsylvania. If you see a line of red and orange crossing the Susquehanna River on the Newark DE doppler radar, you have about 30 to 45 minutes before it hits the UD campus.

- The "Southward" Hook: If a storm is coming up from the South (Dover area), it’s often carrying way more moisture. These are the ones that cause flash flooding on the White Clay Creek.

- Look for the Bright Band: In the winter, you’ll sometimes see a very bright ring on the radar. That’s not necessarily a heavy storm; it’s the "melting level" where snow is turning into rain. It looks intense on the radar because melting snowflakes are huge and reflective, but it's often just a messy slush.

To get the most out of local weather tracking, stop relying on a single source. Check the KDIX radar for the big picture, but keep an eye on the KDOX feed out of Dover for anything creeping up the coast. If you see a discrepancy between the two, the truth is usually somewhere in the middle.

Next Steps for Better Tracking

Download an app that allows you to switch between individual radar stations rather than a "national mosaic." This lets you see the raw data from Mount Holly or Dover without the smoothing filters that big-name weather apps use, which often hide the most dangerous parts of a storm. Check the "Standard" or "Enhanced" radar views on the official National Weather Service website specifically for the Philadelphia/Mount Holly region to get the most scientifically accurate, no-nonsense view of what's heading toward Newark.