You’ve probably heard the rumors. People call it "the easiest Science Regents," or they tell you it’s just common sense about the environment. That’s a dangerous trap. Honestly, New York Regents Biology—now officially labeled the Living Environment Regents—has evolved into a test that cares way more about how you think than how many definitions you’ve memorized. It’s a literacy test disguised as a science exam. If you can’t parse a complex graph or explain why a cell membrane is picky, the vocabulary won't save you.

New York’s graduation requirements are pretty rigid. You need this credit. But the gap between "passing" and "mastery" is where most kids trip up. The state isn't just asking you to identify a mitochondria; they want you to explain why a specific failure in that organelle would make a person feel chronically fatigued. It’s about the "so what?" factor.

Why New York Regents Biology Is Moving Away From Rote Memorization

The New York State Education Department (NYSED) has been slowly shifting the goalposts. Look at the transition toward the New York State P-12 Science Learning Standards (NYSP12SLS), which are heavily influenced by the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS). This isn't just bureaucratic alphabet soup. It means the exam is becoming less about "What is photosynthesis?" and more about "Look at this specific data from an experiment on algae—why did the oxygen levels drop at 2 AM?"

Data analysis is the new king.

If you look at recent exams, almost 40% of the points come from interpreting diagrams, tables, and reading passages. You could be a walking encyclopedia of biological terms and still fail if you struggle to connect a prompt about an invasive species in the Hudson River to the concept of niche competition.

The Literacy Gap

I’ve seen students who know their stuff inside out lose points because they didn't read the phrase "except for" in a multiple-choice question. Or they gave a one-word answer when the prompt asked them to "describe" a process. In the world of the Living Environment Regents, "describe" and "identify" are two completely different beasts. If you just identify when it asked you to describe, you get zero. Brutal, right?

The Four Pillars That Actually Matter

Most review books divide the subject into twenty chapters. That's overkill. If you're trying to prioritize, you basically need to obsess over four main areas.

🔗 Read more: Dr Dennis Gross C+ Collagen Brighten Firm Vitamin C Serum Explained (Simply)

1. Ecology and Human Impact

This is the state's favorite topic because it’s easy to write questions about. They love asking about biodiversity. Specifically, why having more species makes an ecosystem stable. You'll definitely see questions about global warming (don't call it that on the test—use "climate change" or "increased CO2 levels"), acid rain, and how humans mess up phosphorus and nitrogen cycles.

2. Homeostasis: The Balancing Act

Everything in biology comes back to keeping things the same. Feedback loops are a huge deal. Think about insulin and glucagon. When your blood sugar spikes after a slice of New York pizza, your pancreas has to kick into gear. If you can explain the "if-then" logic of a feedback loop, you've conquered a massive chunk of Part B-2 and C.

3. Genetics and Biotechnology

This isn't just Punnett squares anymore. In fact, those are barely on the test. They want to know if you understand how DNA makes proteins. Protein synthesis is the "central dogma" for a reason. You need to know that the shape of a protein determines its function. If the shape changes (mutation!), the protein stops working. Also, get comfortable with CRISPR and gel electrophoresis. The state loves showing those little DNA bands and asking which "suspect" matches the crime scene.

4. Evolution and Natural Selection

Survival of the fittest is a phrase everyone uses, but few students use correctly in a response. Most kids write, "The giraffe stretched its neck to reach the leaves, so its babies had long necks." Incorrect. That's Lamarckian evolution, and it will get you no points. You have to talk about variation, overproduction, and how the environment selects those who already have the "good" traits.

The Lab Practical Requirement: Don't Forget the "Big Four"

You can't even sit for the New York Regents Biology exam unless you've completed 1,200 minutes of hands-on lab time. But more importantly, there is a dedicated section of the test (Part D) that specifically covers four state-mandated labs.

- Making Connections: This is the one where you took your pulse and squeezed a clothespin. It’s about muscle fatigue and how the circulatory and respiratory systems work together.

- The Beaks of Finches: A classic. It’s an evolution simulation. You use different tools (pliers, tweezers) to pick up seeds. It teaches competition and niche.

- Relationships and Biodiversity: This is a "paper lab" mostly, where you compare Botana curis to other species using structural and molecular evidence. Pro-tip: Molecular evidence (DNA) is always more reliable than structural evidence (what it looks like).

- Diffusion Through a Membrane: Starch, glucose, and iodine. You have to remember that starch is too big to move through the membrane, but glucose is small enough. This lab is a goldmine for questions about active vs. passive transport.

Students often treat these labs as "busy work" during the year. Big mistake. Part D is usually the highest-scoring section for students who simply remember what they did in class.

💡 You might also like: Double Sided Ribbon Satin: Why the Pro Crafters Always Reach for the Good Stuff

Cracking the Part C Open-Ended Questions

Part C is where dreams of a 90+ score go to die. It’s all writing.

Here is the secret: The graders use a rubric. They aren't looking for beautiful prose or a five-paragraph essay. They are looking for specific scientific keywords. If the question asks how a vaccine works, and you don't use the words "antigen," "white blood cells," or "antibodies," you're probably not getting the point.

The state loves "Claim, Evidence, Reasoning" structures.

- Claim: The population of deer will decrease.

- Evidence: The graph shows a sharp increase in the wolf population starting in 2010.

- Reasoning: Since wolves are predators of deer, an increase in predators leads to higher mortality rates among the prey population.

Keep it simple. Use "if/then" statements. Don't try to be fancy.

Common Pitfalls to Avoid

A huge mistake is using the word "it."

- Student answer: "It goes into the cell and changes it."

- Grader's thought: "What is 'it'?! The glucose? The ribosome? The virus?"

Be specific. Use the actual names of the molecules and structures. If you mean the mitochondria, say "mitochondria."

📖 Related: Dining room layout ideas that actually work for real life

The Evolution of the Exam in 2025 and 2026

We are currently in a transitional period for New York science. The "Old" Living Environment curriculum is being phased out for the "New" Standards. What does this mean for you? It means the questions are becoming more "phenomenon-based."

Instead of asking a dry question about osmosis, they'll give you a story about a fisherman who accidentally put a saltwater fish into a freshwater tank. You have to apply the biology to the story. This requires a level of mental flexibility that older versions of the New York Regents Biology exam didn't demand.

You also need to be very comfortable with "Error Analysis." They might show you a student's lab setup and ask, "What did this student do wrong?" or "How could they make this experiment more valid?" (The answer is almost always: "Increase the sample size" or "Repeat the trials.")

Practical Steps for Mastery

If the exam is next week, or even next month, don't just read a textbook. That’s passive learning and it’s mostly useless for this specific test.

- Download the last five years of exams. The NYS Regents website has them for free. Do the multiple-choice, but then go straight to the "Scoring Key and Rating Guide." Look at the "Sample Responses." See exactly what the graders accepted as a correct answer. You'll start to see patterns in the language they want.

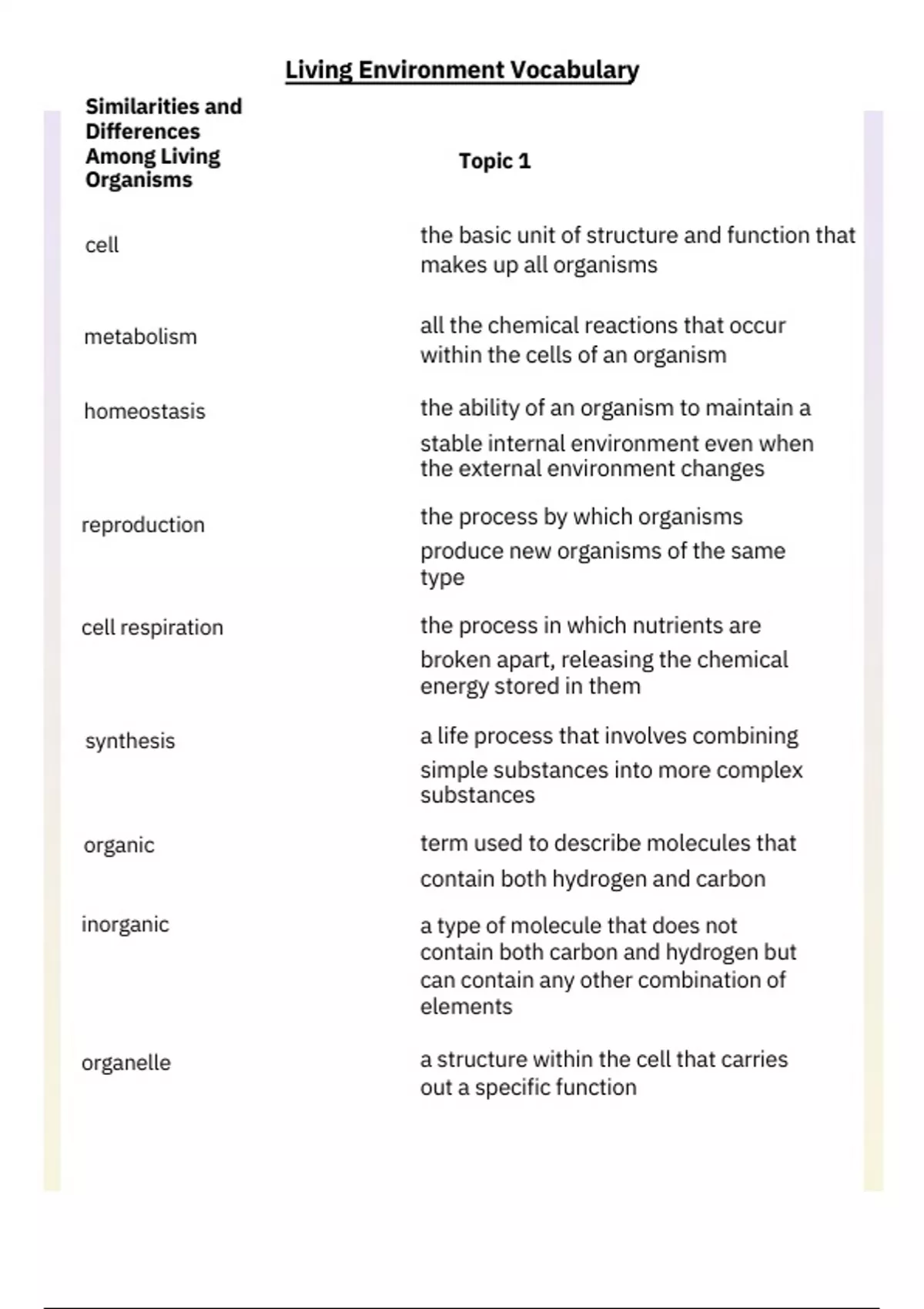

- Focus on the "Big Vocabulary." You don't need to know every obscure protein, but you absolutely must know: Homeostasis, Synthesis, Organelle, Enzyme, Catalyst, Receptor Molecule, Antigen, Antibody, Abiotic, and Biotic. 3. Master the Microscope. There is almost always a question about field of view or how an image looks under a lens (it’s upside down and backward, by the way).

- Graphing is Free Points. You will likely have to draw a graph. Use a pencil. Label your axes. Include units (like "cm" or "seconds"). Connect the dots only if the directions tell you to. If you mess up the graph, you’re throwing away 3–5 easy points.

- Check the "Base Pair" Rule. In genetics, A goes with T, and C goes with G. In RNA, A goes with U. This shows up every single year. It’s an easy point. Don't miss it.

The New York Regents Biology exam is a hurdle, but it’s a predictable one. The state isn't trying to trick you; they are trying to see if you understand the logic of life. Once you stop seeing it as a memory test and start seeing it as a "problem-solving with biology words" test, the whole thing gets a lot easier.

Next Steps for Preparation

Start by taking a practice Part A from a June exam. If you score below a 22/30, your issue is likely content knowledge. If you score high on Part A but struggle with the written sections in Part B-2 and C, your issue is "Scientific Literacy"—you know the facts but don't know how to explain them. Tailor your studying to which of those two buckets you fall into. Focus your energy on the "Relationships and Biodiversity" and "Diffusion Through a Membrane" lab reviews, as these are statistically the most frequently tested lab concepts in Part D.