History books usually start with Columbus. They mention 1492. They talk about the Nina, the Pinta, and the Santa Maria. But if you really look at New World Jewry 1493 1825, the timeline is messier, braver, and way more complicated than a few ships sailing west. It’s a story of survival, secret identities, and a massive economic engine that most people just kind of ignore.

It's wild.

We’re talking about a group of people who were literally running for their lives from the Spanish Inquisition while simultaneously trying to build some of the first global trade networks. They weren't just "settlers." They were refugees with business degrees—well, the 17th-century equivalent, anyway.

The Secret Colonists of the Caribbean

You can't talk about New World Jewry 1493 1825 without talking about the "Conversos." These were Jews who had been forced to convert to Catholicism in Spain and Portugal but kept practicing their faith in secret. When the ships started heading to the Americas, many saw it as a chance to get as far away from the Grand Inquisitor as humanly possible.

Imagine living a double life for decades. In public, you're at Mass. In private, you're lighting candles on Friday night and hoping the neighbors don't smell the lack of pork cooking. This wasn't just a few people; it was a significant demographic shift.

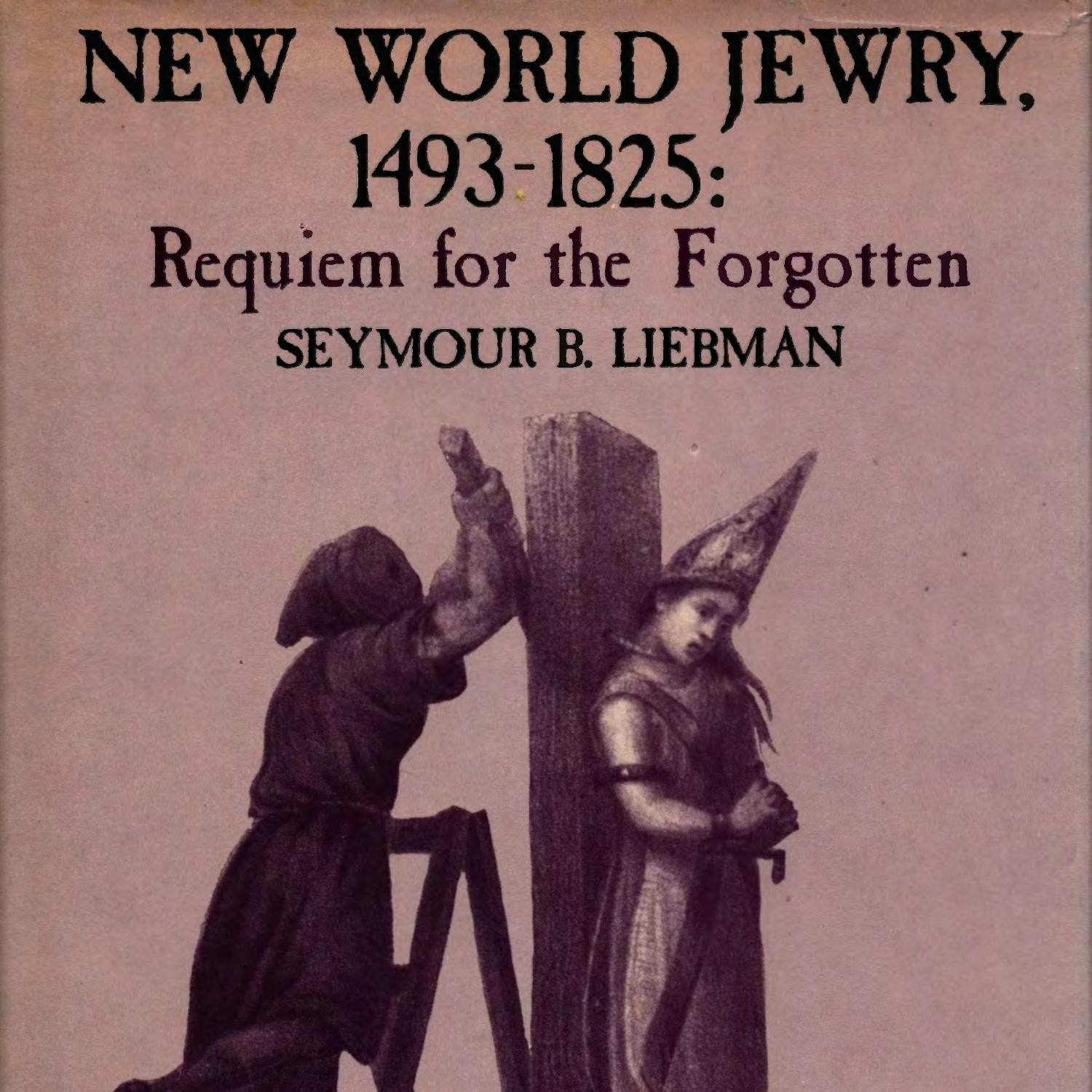

By the time we hit the mid-1500s, Mexico City and Lima had thriving, though underground, Jewish communities. But the Inquisition eventually caught up. It followed them across the ocean. The first recorded auto-da-fé in the New World happened in Mexico in 1574. It’s a dark chapter that reminds us that "religious freedom" wasn't exactly the founding principle for everyone in the beginning.

What Really Happened in Dutch Brazil

If there’s one turning point in the history of New World Jewry 1493 1825, it’s the rise and fall of Dutch Brazil. This is where things get interesting from a "real-world" perspective. For a brief window in the 1600s, the Dutch took over parts of Brazil from the Portuguese.

The Dutch were... different.

👉 See also: How is gum made? The sticky truth about what you are actually chewing

They cared about money. A lot. And they realized that the Sephardic Jews (Jews of Spanish and Portuguese descent) were incredible at trade. So, they let them practice openly. In Recife, you had Kahal Zur Israel—the first synagogue in the Americas. It was a golden age that lasted about twenty minutes. Okay, more like twenty-four years (1630–1654).

When the Portuguese took Brazil back, the Jews had to scramble. Again. This led to a massive diaspora within a diaspora. Some went back to Amsterdam. Some headed to Curaçao. And a tiny group of 23 refugees ended up in a little place called New Amsterdam.

You know it as New York City.

The Sugar Trade and the Economic Reality

We have to be honest about the economics here. New World Jewry 1493 1825 wasn't just about prayer; it was about the "White Gold"—sugar.

Sephardic merchants were the backbone of the sugar trade in the Caribbean. From Barbados to Jamaica, they owned plantations and operated the mills. Because they had family connections in London, Amsterdam, and Hamburg, they could move goods faster than anyone else. It was an early version of a global supply chain.

Historians like Jonathan Israel have pointed out that these Jewish networks were vital to the success of the Atlantic economy. But that success came with a heavy moral price. Like everyone else participating in the 17th and 18th-century economy, Jewish merchants were involved in the slave trade. It’s a part of the history that is often glossed over in older textbooks, but it’s essential to acknowledge if we’re being factually accurate. You can't separate the growth of these communities from the brutal systems they operated within.

Newport and the Fight for Rights

By the 1700s, the focus shifted north. Newport, Rhode Island, became a major hub. Why? Because Roger Williams (the guy who founded Rhode Island) actually believed in separation of church and state. Sorta.

✨ Don't miss: Curtain Bangs on Fine Hair: Why Yours Probably Look Flat and How to Fix It

The Touro Synagogue in Newport is still standing today. It’s a gorgeous building, but it represents something bigger: the transition from "tolerated outsiders" to "citizens."

When George Washington wrote his famous letter to the Hebrew Congregation in Newport in 1790, he wasn't just being polite. He was defining what America was going to be. He said the government "gives to bigotry no sanction." That was a massive deal. For the first time in basically a thousand years, Jews in the Western world were being told they weren't just guests—they were part of the fabric of the nation.

The Demographic Shift of the late 1700s

As we approach the end of the New World Jewry 1493 1825 period, the makeup of the community started to change. Up until about 1750, it was almost entirely Sephardic. These were the elites. They spoke Ladino or Portuguese. They had the old-world connections.

Then came the Ashkenazim (Jews from Central and Eastern Europe).

They were poorer. They spoke Yiddish. They didn't always get along with the Sephardic establishment. It’s a classic immigrant story—the "old guard" looking down on the "new arrivals." By 1825, the Ashkenazi population was starting to overtake the Sephardic one, setting the stage for the massive waves of immigration that would happen later in the 19th century.

Common Misconceptions You Should Probably Forget

"Jews only lived in New York." Wrong. In the colonial era, Charleston, South Carolina, actually had one of the largest and most influential Jewish populations in North America. Savannah, Georgia, was another big one. The South was actually a huge center for Jewish life before the Civil War.

"They were all wealthy merchants." While there were some very rich families (like the Gratzes or the Lopez family), plenty of people were just struggling peddlers, silversmiths, or bakers. Life was hard for everyone.

🔗 Read more: Bates Nut Farm Woods Valley Road Valley Center CA: Why Everyone Still Goes After 100 Years

"Religion was the only thing that kept them together." Actually, it was often language and family ties. Many of these "New World" Jews weren't particularly observant in the way we think of it today. They were bound by their shared history of being kicked out of Europe more than by strict adherence to every single law in the Torah.

How This Impacts Us Now

Understanding New World Jewry 1493 1825 isn't just a history lesson. It’s a blueprint for how minority groups integrate into a dominant culture while trying to keep their own identity.

It’s about the tension between wanting to fit in and wanting to be different.

If you look at the architecture of Charleston or the old cemeteries in Curacao, you see the physical remains of this struggle. These people weren't just "present" in the making of the Americas; they were foundational. They helped fund the Revolution. They built the ports. They connected the Old World to the New in a way that made modern capitalism possible.

Actionable Insights for Further Exploration:

- Visit the Touro Synagogue: If you're ever in Rhode Island, go see it. It’s the oldest synagogue building in the U.S. and a weirdly quiet place to think about how much has changed since 1763.

- Search the Portuguese Inquisition Records: Many of these are now digitized. If you have Sephardic roots, you can sometimes find actual trial transcripts of ancestors who fled to the Americas.

- Read "American Judaism" by Jonathan Sarna: If you want the academic deep dive that isn't boring, this is the gold standard. He breaks down the 1493-1825 period with incredible detail.

- Check out the Mikvé Israel-Emanuel in Curaçao: It’s the oldest continuously used synagogue in the Western Hemisphere. The floor is covered in sand—a tribute to the secret Jews who used sand to muffle the sound of their prayers back in Spain.

The period of New World Jewry 1493 1825 ended just as the modern world was beginning. By the 1820s, the revolutionary wars in South America were finishing up, the United States was expanding, and the old Sephardic world was fading into the new Ashkenazi one. But the footprint they left behind is why the American Jewish experience looks the way it does today.