If you’ve ever stood in a muddy field or a crowded arena waiting for Bobby Weir to rip into that opening slide guitar riff, you know the feeling. It’s gritty. It’s loud. It’s unmistakably the blues. But if you actually listen to new minglewood blues lyrics from a show in 1966 versus one in 1989, you’re basically listening to two different stories.

The Grateful Dead didn’t just cover this song; they lived in it for thirty years, and like any long-term residence, they kept rearranging the furniture. Honestly, the history of this track is a mess of aliases, stolen verses, and geographical confusion that traces back to a tiny lumber town in Tennessee.

The Noah Lewis Connection: Where It All Started

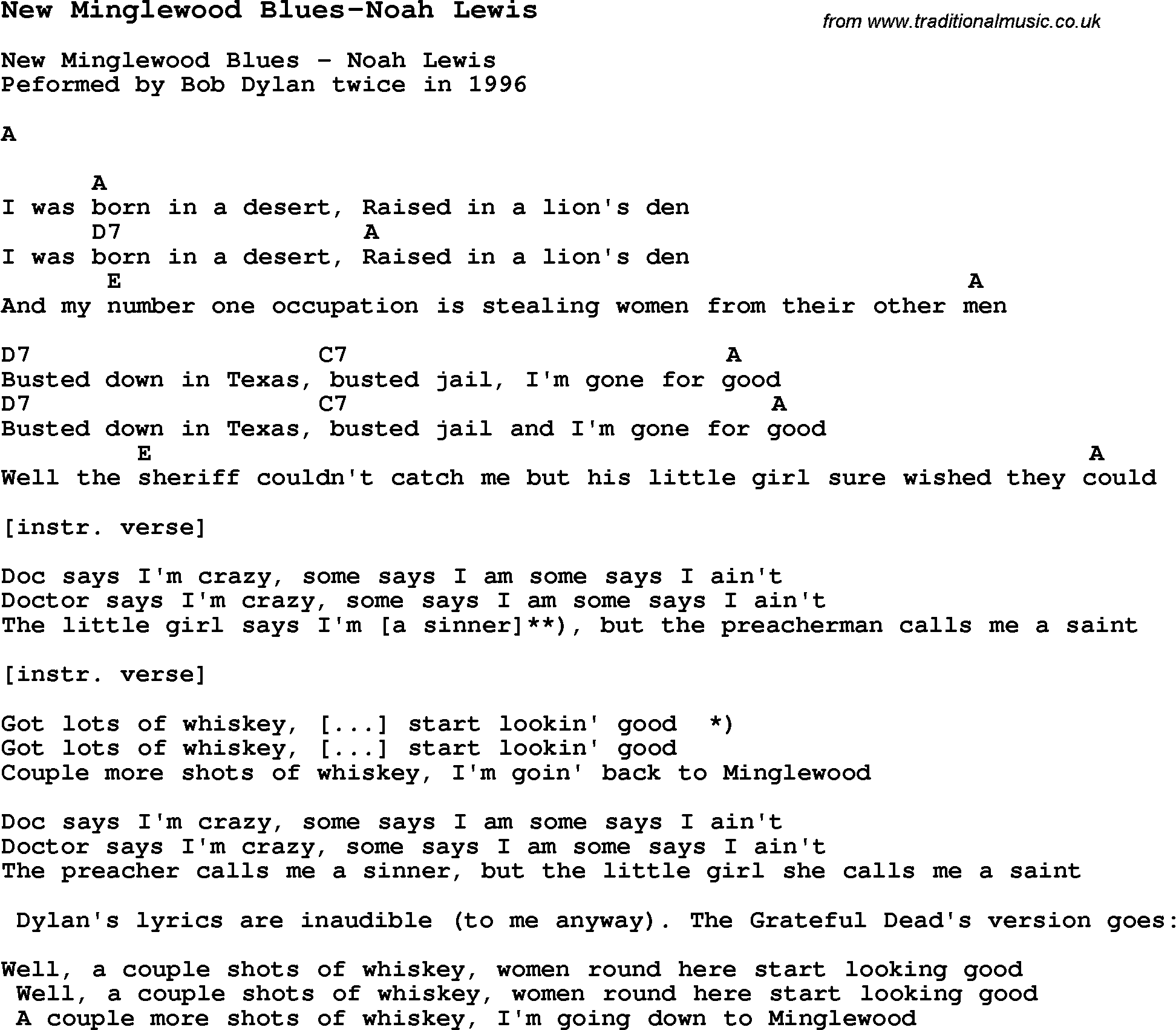

Before the Dead were even a glimmer in Jerry Garcia’s eye, there was Noah Lewis. He was a harmonica virtuoso who could play two harps at once—one with his mouth and one with his nose. Seriously. In 1928, he recorded "Minglewood Blues" with Cannon’s Jug Stompers.

That original version was a warning. It told men not to let women "rule your mind." It was slow, acoustic, and smelled like the Memphis delta. But here is where it gets tricky. Two years later, in 1930, Lewis recorded "New Minglewood Blues" with his own jug band. He ditched the "don't let a woman rule your mind" bit and brought in the heavy hitters. We're talking about the "born in a desert, raised in a lion's den" lines.

He didn't even write all of those. He basically "sampled" them (in the old-school blues way) from Texas Alexander’s "Water Bound Blues" and Charley Patton’s "It Won’t Be Long." In the 1920s, lyrics were like common property. If a line worked, you used it.

New New Minglewood Blues: The 1967 Shake-Up

When the Grateful Dead recorded their first album in 1967, they were still heavily influenced by Mother McCree's Uptown Jug Champions. They took Lewis’s 1930 version and sped it up until it screamed. They called it "New, New Minglewood Blues."

Why the extra "New"? Probably because they knew they were covering a song that was already a "New" version of an older one. On that first record, the credits listed a guy named "McGannahan Skjellyfetti." That wasn't a real person. It was a pseudonym the band used for group compositions, supposedly named after a character in a Kenneth Patchen novel (or maybe just a cat one of them owned).

📖 Related: Break It Off PinkPantheress: How a 90-Second Garage Flip Changed Everything

In this 60s era, the lyrics stayed somewhat close to the Memphis roots:

- "If you're ever in Memphis, better stop by Minglewood."

- "Take a walk downtown, the women sure look good."

But then, the song disappeared. They shelved it in 1971. For five years, Minglewood was silent.

Shakedown Street and the "All New" Era

When the band brought the song back in 1976, it had a different swagger. By the time it hit the Shakedown Street album in 1978, it was titled "All New Minglewood Blues." This is the version most modern listeners recognize. It’s funkier. It’s slicker.

The lyrics underwent a massive overhaul during this period. The Memphis references started to fade, replaced by a more nomadic, outlaw vibe. Bobby started singing about being a "wanted man in Texas" who "busted jail" and was "gone for good."

The Famous "Doctor and Preacher" Verse

This is the peak of the song's lyrical evolution. You know the one:

"Yes and the doctor call me crazy, some says I am, some says I ain't.

The preacher man call me sinner, but his little girl call me a saint."👉 See also: Bob Hearts Abishola Season 4 Explained: The Move That Changed Everything

It’s peak Bob Weir. It’s got that rebellious, tongue-in-cheek humor that defined the Dead’s mid-to-late career. Interestingly, this verse wasn't in the original 1930s blues tracks. It was a later addition that gave the song a personality beyond just "standard blues cover."

Tracking the Changes: A Quick Breakdown

If you're trying to figure out which version you're listening to on a bootleg, look for these lyrical "tells":

The 1960s (New New Minglewood)

The location is Memphis. The key is usually C. The lyrics focus on "stealing women from their men" and the "if you can't believe me" verse. It feels like a garage band playing jug music.

The Late 70s (All New Minglewood)

The location shifts. Texas enters the chat. The key moves to A. This is where the "wanted man" and "sheriff's little girl" lines show up.

The 1980s and 90s (The "T for Texas" Era)

By the 80s, Bobby started throwing in bits of "T for Texas" (Blue Yodel No. 1) by Jimmie Rodgers. He also started changing "stealing women from their men" to "stealing women from their other men" or even "their other men and women." He was keeping it current. Sorta.

Why Minglewood?

So, what is Minglewood anyway? People used to think it was just a metaphor for a "hot spot" or a rough part of town.

✨ Don't miss: Black Bear by Andrew Belle: Why This Song Still Hits So Hard

Actually, it was a real place. Menglewood (spelled with an 'e') was a company town owned by the Mengel Box Company in Tennessee. It was a lumber camp and sawmill town about 80 miles north of Memphis. For a traveling musician like Noah Lewis, it was a place where workers had cash in their pockets and a desire to blow it on whiskey and music on Saturday nights.

By the time the Dead were playing it in the 80s, "Minglewood" had become a mythical place. It wasn't about a sawmill anymore. It was about a state of mind—a place where the rules didn't apply and the preacher's daughter was always looking for a way out.

Actionable Insights for the Dedicated Head

If you want to truly appreciate the evolution of new minglewood blues lyrics, don't just stick to the studio albums. The live recordings are where the real story is told.

- Listen to 1966-05-19: This is one of the earliest known recordings. It’s raw, fast, and shows the band’s jug band roots.

- Compare it to 1977-05-08 (Barton Hall): This is the definitive "All New" version. The rhythm is tight, and the lyrics are fully formed in their "Texas outlaw" phase.

- Check out a 1980s version: Watch how Weir plays with the "saint/sinner" line. Sometimes he’d drag out the "some says I ain’t" part just to see how the crowd would react.

The song is a living document. It started in a Tennessee labor camp, moved through the Memphis blues scene, and ended up as a stadium anthem for a generation of misfits. The lyrics changed because the band changed. They grew from kids playing loud blues into seasoned road warriors who actually felt like "wanted men" on the run.

To get the full picture, go back and find the original Noah Lewis recording from 1930. Listen to his harmonica. Then put on a high-energy 1980 version. You'll hear the same "lion's den" and the same "desert," but you'll also hear fifty years of American history moving through the notes.

Next Steps:

Grab a copy of the Shakedown Street album and compare the "All New Minglewood Blues" lyrics to the 1967 debut album version. Note the specific changes in geography and character—it’s the best way to see how the band’s songwriting philosophy shifted from literal covers to narrative reinvention.