Ever tried to assemble an IKEA dresser and found yourself staring at a flat piece of cardboard, wondering how on earth it becomes a drawer? That’s basically the real-world version of dealing with nets of 3D objects. It looks like a random cross or a weirdly shaped "T," but in a few folds, it’s a cube. Or a pyramid. Or a truncated icosahedron if you're feeling particularly masochistic.

Honestly, our brains aren't naturally wired to flatten the world. We live in 3D. So, when a teacher or a textbook asks you to "unfold" a cylinder in your mind, it feels like a mental glitch. But understanding these flat patterns is actually the secret sauce behind everything from Amazon shipping boxes to the way architects design complex skyscrapers. It’s the bridge between a 2D drawing and a physical thing you can hold.

What is a Net, Really?

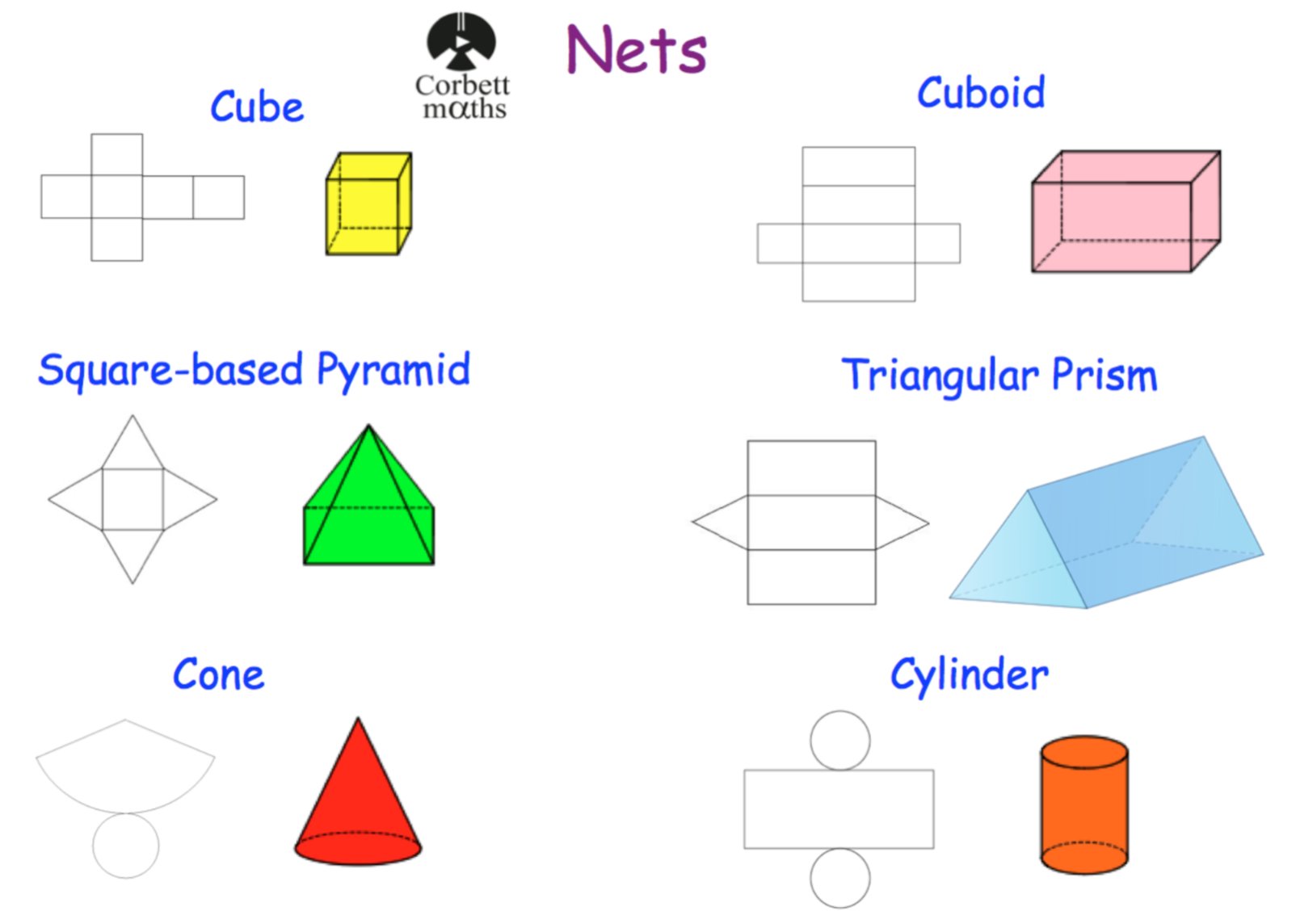

Think of a net as the "skin" of a shape. If you took a cereal box and carefully sliced along the edges until it laid perfectly flat on the kitchen table without any pieces overlapping, you’ve just made a net.

It’s a two-dimensional skeleton. Every 3D polyhedra has at least one net, but most have way more than you’d think. Take the humble cube. Most people can picture the "cross" shape. But did you know there are exactly 11 distinct nets that can fold into a cube? Not ten. Not twelve. Eleven. If you find a twelfth, you’ve either broken the laws of geometry or you’ve accidentally created a shape that overlaps itself.

The Geometry of Flattening Out

Mathematically, we’re talking about topology and surface area. When we talk about nets of 3D objects, we’re essentially mapping the surface area of a solid onto a single plane. This is a huge deal in manufacturing. If you’re a packaging designer for a high-end perfume brand, you don't just "make a box." You have to calculate the most efficient net possible to minimize paper waste. Waste costs money.

The complexity spikes once you move past the "Platonic Solids"—those five perfectly symmetrical shapes like the tetrahedron (four faces) or the dodecahedron (twelve faces).

For example, a cylinder is weirdly deceptive. You’d think it’s just a circle and a tube, right? But when you flatten that middle tube, it’s just a rectangle. The net of a cylinder is literally two circles and one rectangle. A cone is even weirder—it’s a circle and a sector of a larger circle that looks like a PAC-MAN.

Why Your Brain Finds This Hard

There’s a specific cognitive skill called mental rotation. Some people are born with it dialed up to eleven; others feel like their brain is buffering. Research from the Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience suggests that mental rotation involves the parietal lobe. When you look at a net of a 3D object and try to "fold" it in your head, you're performing a series of rapid-fire spatial transformations.

🔗 Read more: Blue Tabby Maine Coon: What Most People Get Wrong About This Striking Coat

It’s hard because you have to keep track of which edges will meet. If side A meets side B, does that leave a gap at the top? You have to hold the "folded" image in your working memory while simultaneously analyzing the "unfolded" image.

It’s exhausting.

But it’s also a muscle. You can actually train your brain to get better at this. This is why primary schools lean so heavily on "manipulatives"—physical cut-outs that kids can actually fold. It builds that neural pathway between the 2D and 3D worlds. Without that physical practice, the math stays abstract and annoying.

The Surprising World of Non-Convex Nets

Here is where it gets kind of wild. Most of the nets we talk about are for "convex" shapes—shapes where all the corners point outwards. But what about "non-convex" or "star" shapes?

Designing a net for a complex, spiked object is a nightmare. This is where software like AutoCAD or specialized origami simulators come in. Mathematician Erik Demaine at MIT has done some incredible work on the "foldability" of shapes. He proved that you can basically fold any 3D surface from a single sheet of paper, provided the net is complex enough.

Think about that.

A life-sized paper Ferrari? Possible. A folded paper replica of the Eiffel Tower from one sheet? Theoretically, yes. The net would just look like a chaotic spiderweb of millions of tiny lines.

💡 You might also like: Blue Bathroom Wall Tiles: What Most People Get Wrong About Color and Mood

Common Mistakes (And How to Spot a "Fake" Net)

Not every collection of 2D shapes is a net. You'll often see "trick" questions on geometry tests where they show a pattern that looks like it should work, but it doesn't.

- The Overlap: If two faces occupy the same space when folded, it's not a net.

- The Missing Face: If you're making a cube net and you only have five squares, you're making an open box, not a cube.

- The Misaligned Edge: In a pyramid, the triangular sides must all meet at a single point (the apex). If the triangles are different sizes or attached to the wrong sides of the base, the apex will never close.

A good rule of thumb? Count the faces first. If you’re trying to make an octahedron, you better have eight triangles on that paper. If you have seven, stop. You’re done before you started.

The Practical Side: Where This Actually Matters

This isn't just for 5th-grade math class.

Take the medical field. Stents—those tiny mesh tubes used to keep arteries open—are often manufactured as flat patterns and then "folded" or expanded into their 3D shape inside the body. It’s high-stakes geometry. If the "net" of that stent isn't perfect, it won't expand correctly, and that’s a life-or-death problem.

In fashion, a "pattern" is just a net for a human body. A shirt is a 3D object. The pieces of fabric are the 2D net. Tailors have been masters of 3D-to-2D mapping for centuries. They understand that you can’t wrap a flat sheet of fabric around a curved shoulder without adding "darts" (which are basically just tiny adjustments to the net's geometry).

Exploring Complex Polyhedra

Beyond the cube, things get beautiful. The truncated icosahedron—which is the technical name for a classic soccer ball—has a net made of 12 pentagons and 20 hexagons.

Imagine trying to visualize that folding together. It’s a masterpiece of spatial coordination. Or look at the rhombicuboctahedron (try saying that three times fast). It has 26 faces. The net looks like a sprawling map of squares and triangles.

📖 Related: BJ's Restaurant & Brewhouse Superstition Springs Menu: What to Order Right Now

Architects like Buckminster Fuller used these principles to create geodesic domes. He realized that by using triangular nets, he could create structures that were incredibly strong but used minimal material. He was essentially playing with 3D nets on a massive scale.

How to Master Nets of 3D Objects

If you want to actually get good at this, stop looking at screens.

- Print and Cut: Go find a PDF of different nets. Print them out. Cut them. Feel how the edges meet. There is no substitute for the tactile feedback of paper.

- The "Edge-Coloring" Trick: If you're looking at a net on a piece of paper, try coloring the edges that you think will touch. If you color one edge red, find its "partner" and color it red too. If you end up with three edges that all need to be red, you know the net is impossible.

- Work Backwards: Take a cardboard box (like a small juice carton). Carefully unfold it. See where the manufacturer put the "tabs" for the glue. Those tabs aren't technically part of the geometric net, but they're essential for the 3D object to exist in the real world.

- Use Software: Programs like GeoGebra allow you to drag a slider and watch a 2D net slowly fold into a 3D shape. It’s like a cheat code for your brain's spatial visualization center.

Beyond the Basics

We often think of nets as being static. But in the world of 4D geometry, mathematicians talk about "tesseracts" (4D cubes). Just like a 3D cube can be unfolded into a 2D net of squares, a 4D tesseract can be "unfolded" into a 3D net of cubes.

Salvador Dalí famously painted this in Corpus Hypercubus, showing a 3D net of a 4D cube. It’s mind-bending stuff. It reminds us that nets of 3D objects are just one level of a much deeper mathematical reality.

Whether you're just trying to help a kid with their homework or you're an engineer designing the next foldable smartphone, the logic is the same. It's all about seeing the potential in the flat. It's about knowing that a few strategic folds can turn a boring piece of paper into something that holds volume, provides strength, or even saves a life.

Geometry isn't just lines on a page. It's the blueprint for everything around us.

Actionable Next Steps

To truly wrap your head around this, start with a physical challenge. Find a standard square tissue box. Before you throw it in the recycling, carefully pull the glued seams apart. Lay it flat. Trace the outline on a piece of paper. Now, try to draw a different net that would create that same box. Move one of the side flaps to a different edge. Does it still work? Test it. By physically manipulating the shapes, you move the concept from "abstract math" to "spatial intuition." This is the fastest way to improve your mental rotation skills and stop being intimidated by complex diagrams.