You’ve probably seen it in a middle school textbook. A weird, T-shaped drawing of squares that’s supposed to magically turn into a cube. That flat drawing is a net. Basically, if you took a cardboard box and sliced it along the edges until it laid completely flat on the floor, you’d have a net. It sounds simple. It isn't.

Most people actually struggle with nets of 3D figures because our brains aren't naturally wired to translate 2D layouts into 3D volumes instantly. We’re great at catching a ball or walking through a door, but flattening a dodecahedron? That’s a nightmare for spatial reasoning.

The Geometry of Flattening Out

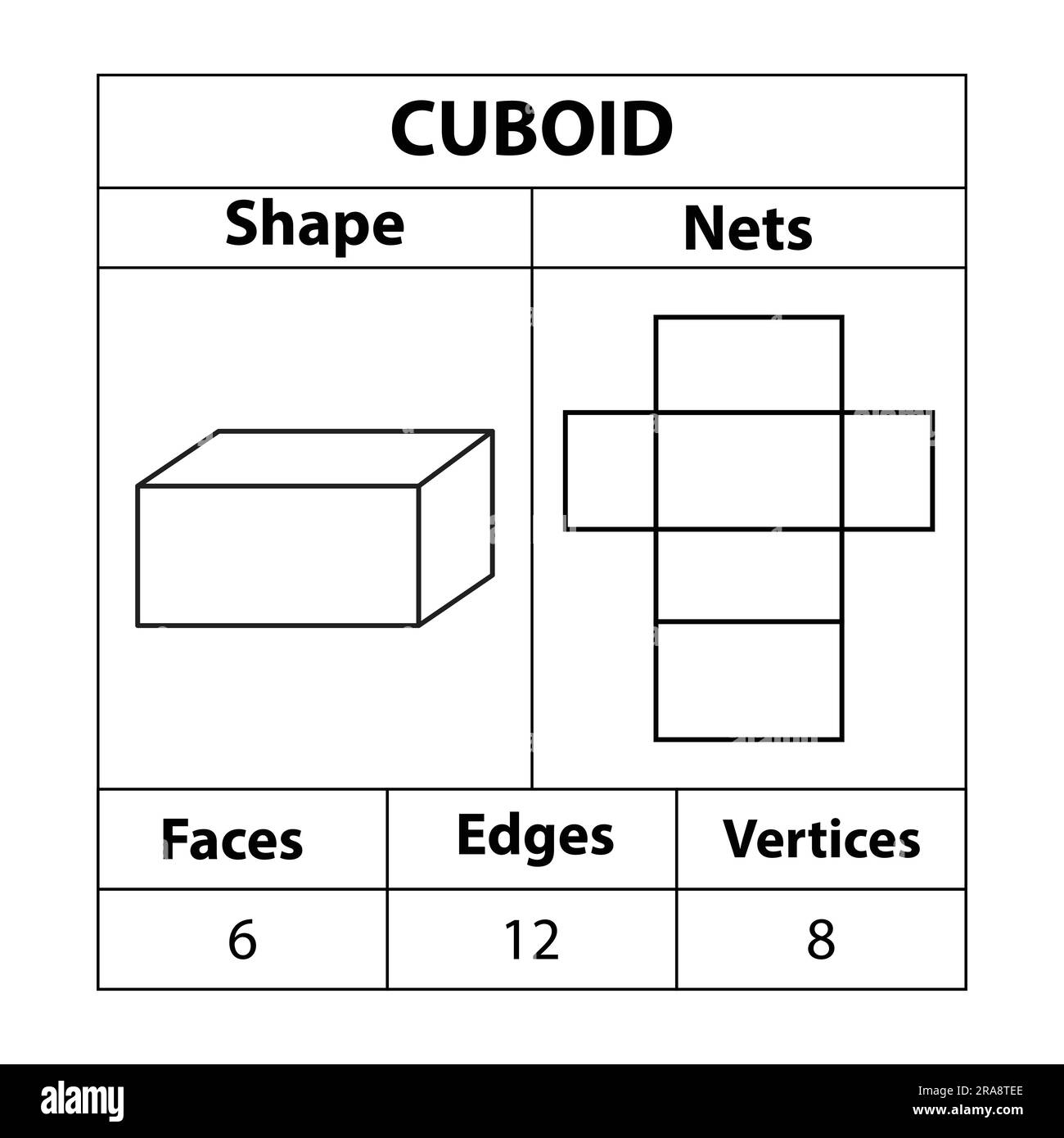

A net is a two-dimensional shape that can be folded to form a three-dimensional object. Every face of the 3D solid must be represented in the net. They have to be connected at the edges. If you have a cube, you need six squares. If you’re looking at a triangular prism, you need two triangles for the bases and three rectangles for the sides.

Think about a soda can. If you cut off the top and bottom circles and then sliced the remaining cylinder straight down the side, what would you get? Most kids guess it stays curved. It doesn't. It becomes a perfect rectangle. That’s the core of understanding how 3D shapes work in a 2D world.

There isn't just one way to draw a net for a specific shape. For a simple cube, there are actually eleven different nets. Eleven! Some look like a cross, some look like a zig-zag staircase. But they all fold into the exact same cube. If you try to make a net and the squares overlap when you fold it, you've failed. It's no longer a net; it's just a mess of paper.

Why Nets of 3D Figures Drive Engineering

This isn't just about passing a math quiz. The entire packaging industry—a multi-billion dollar sector—is built on the logic of nets. Companies like Amazon or FedEx don't store boxes. They store nets. Thousands of flat sheets of corrugated cardboard stacked high in warehouses.

💡 You might also like: Why a Map of Earth with Tectonic Plates is Never Actually Finished

When you order a new pair of shoes, that box started as a single sheet of material. Die-cutting machines use precise mathematical nets to punch out shapes that can be folded quickly by machines or humans. If the net is off by even a millimeter, the tabs won't fit into the slots. The box collapses. Your shoes get damaged.

Sheet metal fabrication works the same way. When engineers build the chassis for a computer or a ventilation duct for a skyscraper, they don't start with a solid block of metal and hollow it out. That's too expensive. They take a flat sheet of steel or aluminum, calculate the nets of 3D figures required for the design, and use CNC lasers to cut them. Then, high-pressure brakes bend them into shape.

The Tricky Shapes: Spheres and Curvature

Here is a weird fact: You cannot make a perfect net of a sphere.

It’s mathematically impossible. This is why every map of the Earth you’ve ever seen is technically a lie. To flatten a sphere onto a 2D plane, you have to stretch it or tear it. This is known as Theorema Egregium, a concept developed by Carl Friedrich Gauss. If you try to peel an orange and lay the skin flat, it ripples or breaks.

Cartographers have spent centuries trying to solve this. The Mercator projection is one attempt, but it makes Greenland look as big as Africa. It isn't. Not even close. Other "nets" for the Earth, like the Dymaxion map created by Buckminster Fuller, try to minimize this distortion by turning the Earth into a 20-sided icosahedron before flattening it. It's a clever workaround, but it’s still an approximation.

💡 You might also like: Why You Just Saw This Password Appears in a Data Leak and What to Do Now

Visualizing the Fold

How do you get better at this? You have to stop looking at the paper and start looking at the edges.

When you're looking at a net, pick one face to be the "base." Imagine it sitting heavy on a table. Then, mentally fold the other faces up around it.

- Pyramids: Usually have a central polygon (square, triangle, pentagon) with triangles hanging off each side.

- Prisms: Two identical polygons (the bases) connected by a series of rectangles.

- Cones: These are the weirdest. A net of a cone looks like a circle and a "pac-man" shaped sector of a larger circle.

It's about vertex counting. In a cube, three edges meet at every corner (vertex). When you look at a flat net, you have to be able to identify which points on the flat paper will touch each other once the shape is closed. If you find a point where four edges are supposed to meet but your net only provides three, your shape won't close.

Common Pitfalls in Spatial Reasoning

Most mistakes happen because people forget the "overlap" rule. In a net, no two faces can occupy the same space.

Another big one? Miscounting the faces. A hexagonal prism has eight faces: two hexagons and six rectangles. If your net only has five rectangles, you’re going to have a very airy, unfinished prism.

Teachers often use "unfolding" as a diagnostic tool for spatial intelligence. It’s a standard part of many IQ tests and civil service exams. Why? Because it proves you can manipulate 3D objects in your "mind's eye." If you can't visualize how a flat piece of paper becomes a pyramid, you might struggle with tasks like architectural drafting or even complex furniture assembly.

🔗 Read more: 8 divided by 75: Why This Specific Decimal Pops Up Everywhere

Modern Tech and 3D Modeling

Nowadays, we have software that handles the heavy lifting. Programs like AutoCAD, SolidWorks, or even paper-craft software like Pepakura Designer take 3D models and "unroll" them automatically.

In the world of gaming, this is called UV mapping. When a character artist creates a 3D monster, they have to "unwrap" the monster's skin into a 2D image so they can paint the textures. If they don't create a clean net (the UV map), the monster's scales or fur will look stretched and distorted in the game. It’s essentially the same math used in a 6th-grade classroom, just applied to a dragon's wing.

Practical Steps for Mastering Nets

If you actually want to get good at this, or help a student understand it, don't just stare at a screen.

- Sacrifice a cereal box. Seriously. Take an empty box of Cornflakes and try to cut it along the edges to make it flat. Try to do it without making any extra cuts. See how the tabs work? That's a real-world net.

- Use the "Base Method." Always identify the bottom of the shape first. Label it. Then label what should be the "Front," "Back," and "Sides." If you end up with two "Tops," your net is wrong.

- Check for symmetry. Many nets are symmetrical, but they don't have to be. An L-shaped arrangement of four squares with one square on either side of the "stem" is the most common cube net, but a "zipper" pattern works too.

- Count the vertices. This is the pro move. A cube has 8 vertices. In a flat net, some of these vertices are "split" and appear multiple times. When you fold it, they have to merge back into exactly 8 points.

Understanding nets of 3D figures changes how you see the world. You start seeing the flat patterns in everything—from the cardboard sleeve on your coffee cup to the complex paneling on a car's body. It's the bridge between a flat idea and a physical reality.

To take this further, start practicing with non-standard shapes. Try to visualize the net of a truncated tetrahedron or a pentagonal dipyramid. Once you move past basic cubes and prisms, the real challenge of spatial geometry begins.