Neptune is a weird place. It’s a giant, blue ball of gas and ice sitting about 2.8 billion miles away from the sun, whipped by supersonic winds that would shred a steel building. But honestly, the weirdest part isn't the planet itself. It's the neighborhood. When you look at the Neptune number of moons, you aren't just looking at a static list in a textbook. You’re looking at a dynamic, chaotic collection of captured asteroids, shattered remains, and one massive, "backward" satellite that probably shouldn't be there at all.

As of right now, we recognize 16 moons orbiting Neptune.

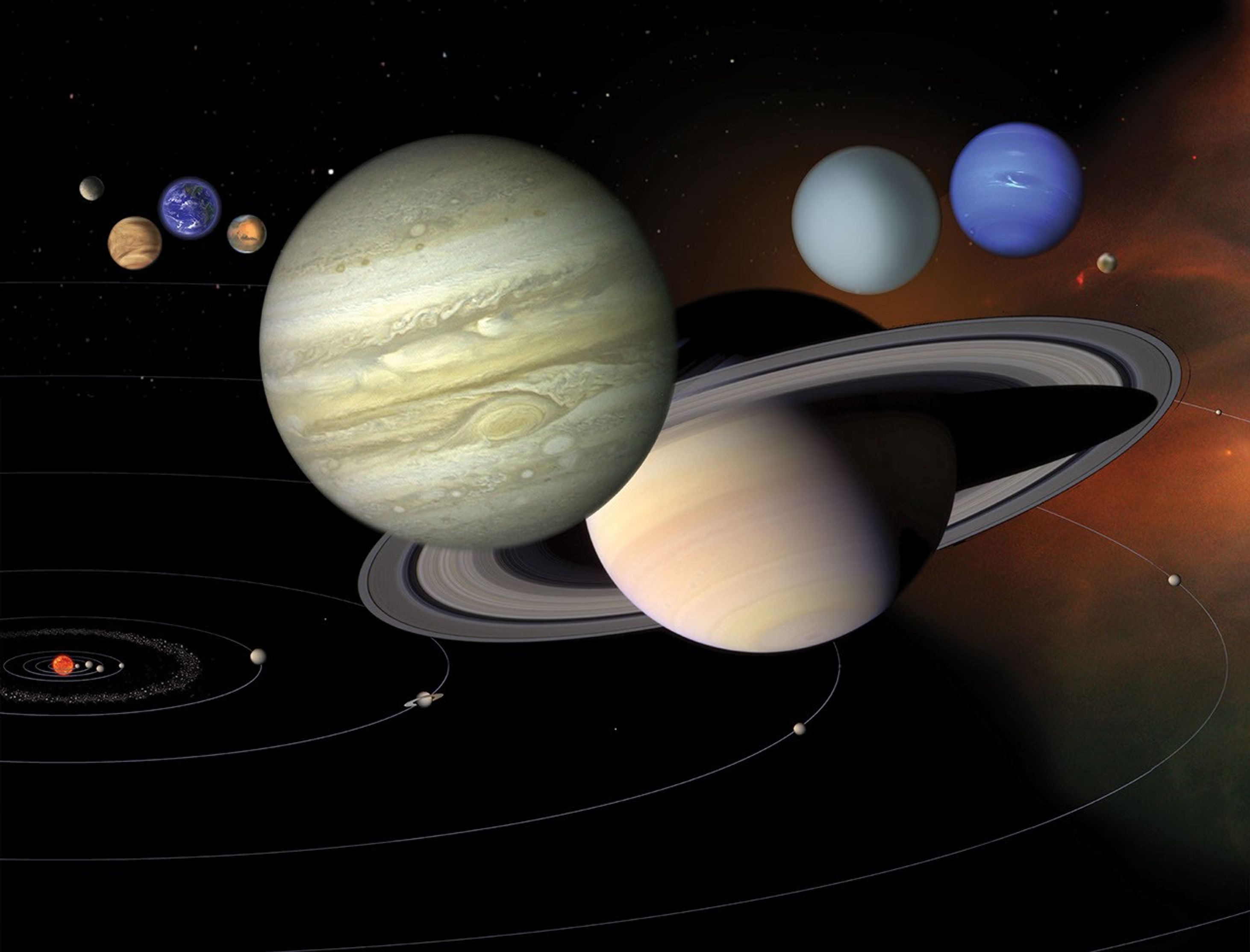

That number might seem low compared to Jupiter’s nearly 100 or Saturn’s 146, but Neptune’s distance makes it incredibly hard to spot the small stuff. We didn't even know most of them existed until Voyager 2 screamed past in 1989. For decades, the count sat at 14. Then, in early 2024, Scott Sheppard and his team at the Carnegie Institution for Science used massive ground-based telescopes to find two more tiny, irregular moons. It’s a reminder that space isn't "settled." We’re still finding pieces of the puzzle.

The Big One and the Oddballs

Triton is the undisputed king of the Neptunian system. It’s huge. It accounts for about 99.5% of all the mass currently in orbit around Neptune. If you took all the other moons, ground them up, and weighed them, they’d be a rounding error compared to Triton.

What makes Triton fascinating—and kinda scary if you’re another moon—is that it orbits in the "wrong" direction. This is what astronomers call a retrograde orbit. While Neptune spins one way, Triton moves the other. Because of this, we’re almost certain Triton didn't form from the same dust cloud that built Neptune. It’s a kidnapped object from the Kuiper Belt, the icy debris field past the planets. Imagine a massive, frozen world wandering through space until it got too close to Neptune's gravity and got yanked into a permanent, lonely circle.

When Triton arrived, it likely acted like a wrecking ball. Its massive gravity would have cleared out Neptune's original moons, smashing them together or flinging them into deep space. The moons we see today, like Proteus or Despina, are probably "second generation" moons—the leftovers that clumped together after Triton’s chaotic arrival settled down.

The Inner Moons: A Tight Squeeze

Close to the planet, things get crowded. You have Naiad, Thalassa, Despina, Galatea, Larissa, Hippocamp, and Proteus. These are mostly small, lumpy objects that look more like potatoes than planets.

Hippocamp is a particularly interesting case. It was discovered by Mark Showalter in 2013 using Hubble Space Telescope images. It’s tiny—only about 20 miles across. It orbits so close to the much larger moon Proteus that scientists think Hippocamp might actually be a broken-off piece of Proteus, chipped away by a massive comet impact billions of years ago. Space is basically a long game of cosmic billiards.

Naiad and Thalassa are locked in a "dance of avoidance." They orbit so close to each other that their paths should bring them dangerously near, but they’ve settled into a resonant pattern where Naiad weaves up and down in a zigzag pattern relative to Thalassa. They never get closer than about 2,200 miles. It’s a perfect, delicate balance that has lasted for eons.

The 2024 Discoveries and the Outer Reach

Finding a moon at Neptune is like trying to see a charcoal briquette against a black velvet curtain from three miles away. It’s dark out there. The sun is just a very bright star. This is why the Neptune number of moons jumped from 14 to 16 just recently.

Scott Sheppard, Marina Brozovic, and Bob Jacobson used the Magellan telescope in Chile and the Subaru telescope in Hawaii to spot S/2021 N1 and S/2002 N5. These names are just placeholders until the International Astronomical Union (IAU) gives them proper names from Greek or Roman mythology, specifically related to the Nereids or sea gods.

- S/2002 N5: This one is about 14 miles wide and takes almost 9 years to go around the planet once.

- S/2021 N1: This one is even smaller, roughly 3 miles across. It’s way out there, taking 27 years to complete a single orbit.

These are "irregular" moons. Unlike the inner moons that stay in neat, circular paths around Neptune's equator, these outer moons have wild, looping orbits. They were likely captured by Neptune's gravity long after the planet formed. Their orbits are so large and slow that they barely feel the planet's influence compared to the inner family.

Why Does the Number Keep Changing?

You might wonder why we can't just count them once and be done with it. The reality of modern astronomy is that "discovery" is often a process of math and patience rather than a "Eureka!" moment.

To find the newest moons, astronomers had to take dozens of long-exposure images. But you can't just leave the shutter open, or the stars will smear into lines. Instead, they took many short exposures and "stacked" them, shifting the images to match the predicted movement of Neptune. It’s like trying to find a specific person in a crowded stadium by layering photos until everyone else blurs out and the one person staying in their seat becomes visible.

🔗 Read more: Apple Redeem Gift Card: How to Actually Get Your Money’s Worth Without the Headache

The current Neptune number of moons is 16, but most experts expect that to grow. We probably haven't found everything in the 5-mile to 10-mile range yet. Every time our camera sensors get more sensitive or our software gets better at filtering out "noise," we find another tiny speck of rock circling the blue giant.

The Death of Triton

There is a dark side to Neptune’s moon count. It’s going to go down eventually.

Because Triton orbits in the opposite direction of Neptune’s rotation, tidal forces are slowly dragging it inward. It’s losing energy. Every year, it gets a tiny bit closer to the planet’s atmosphere. In about 3.6 billion years, Triton will cross the Roche limit. That’s the point where Neptune’s gravity becomes stronger than the gravity holding Triton together.

Triton will be ripped apart.

When that happens, the Neptune number of moons will technically drop, but the planet will gain something spectacular: a ring system that would put Saturn to shame. The shattered remains of Triton will spread out into a shimmering, icy disc. We’re living in a specific window of time where Neptune has a giant moon; in the distant future, it will just be the planet with the most beautiful rings in the solar system.

🔗 Read more: Why the Walkie Talkie Phone 2000s Obsession Still Makes Sense Today

Exploring the Unknown

We haven't been back to Neptune since 1989. Everything we know about the newer moons comes from the Hubble Space Telescope or massive observatories on Earth. There are proposals like the "Neptune Odyssey" mission that could launch in the 2030s, but for now, we’re squinting through the dark.

Understanding the moons helps us understand the early solar system. These small, irregular rocks are like time capsules. They haven't changed much in billions of years. By studying their orbits and colors, we can figure out where they came from—whether they were born near the sun and kicked out, or if they formed in the cold, dark fringes of the Kuiper Belt.

Actionable Steps for Amateur Astronomers

If you're interested in keeping up with the shifting count of moons in our solar system, here is how you can stay informed without needing a PhD:

- Follow the Minor Planet Center (MPC): This is the official clearinghouse for all moon and asteroid discoveries. When a new moon is confirmed, it appears here first.

- Use Simulation Software: Apps like Stellarium or Eyes on the Solar System (by NASA) allow you to track Neptune’s position and see the orbits of its largest moons in real-time.

- Check the "S/" Designations: When you see a moon named something like S/2021 N1, the "S" stands for satellite, 2021 is the year the data was first captured, and "N" stands for Neptune. If you see these names in news headlines, it means a new discovery is being vetted.

- Monitor the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) Feed: While JWST focuses on deep space, it occasionally takes stunning infrared photos of Neptune that reveal the heat signatures of even tiny moons.

Neptune is a frontier. Sixteen moons is the count today. Tomorrow? Who knows. The more we look, the more we realize that the edge of our solar system is a lot more crowded than we ever imagined.