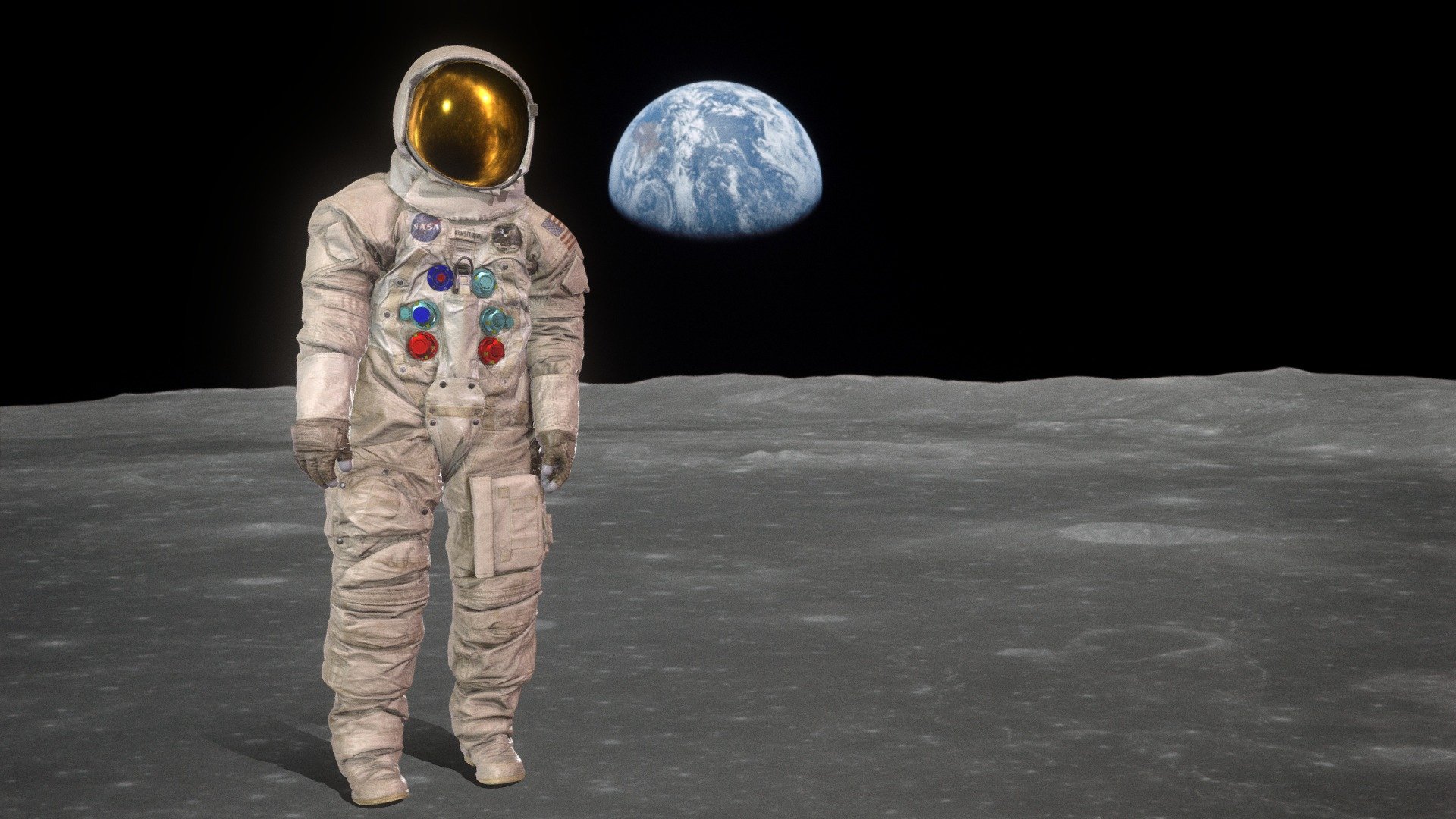

You’ve seen the grainy footage a thousand times. That bulky, marshmallow-like figure hopping across the lunar dust. It’s the ultimate icon of the 20th century. But honestly, most people look at the neil armstrong space suit and see a fancy jumpsuit.

They’re wrong.

It wasn’t a garment. It was a one-man spacecraft. A custom-built, pressurized, life-sustaining vessel that had more in common with a submarine than a pair of overalls. If a single stitch had failed, the mission wouldn't just be over—Armstrong would have been dead in seconds.

The Bra Manufacturers Who Went to the Moon

Here is a bit of trivia that usually floors people: the neil armstrong space suit was built by the International Latex Corporation. You might know them better by their brand name, Playtex.

Yes, the bra and girdle company.

NASA initially went to big-name military contractors. The engineers there built rigid, armor-like suits that looked like something out of a 1950s sci-fi flick. The problem? You couldn't move in them. When ILC submitted their design, they used their expertise in latex and 3D-stitching to create something flexible.

They won the contract because they knew how to make garments that moved with a human body while maintaining their shape.

The seamstresses were the unsung heroes here. We’re talking about precision sewing where a 1/32-inch mistake was a catastrophe. There was no room for error. Every suit was x-rayed twice to make sure no pins were left inside. Imagine floating 240,000 miles from home and getting poked by a stray needle in your pressurized bladder. Not ideal.

Why the Boots in the Museum Don't Match the Prints

If you ever go down a late-night internet rabbit hole, you’ll find conspiracy theorists claiming the moon landing was faked because the boots on Armstrong’s suit in the Smithsonian have smooth soles, but the famous footprint on the moon has treads.

📖 Related: Who Was the Inventor of the Calculator? The Messy Truth Behind the Buttons

Basically, it's a misunderstanding of how the gear worked.

The neil armstrong space suit (the A7L model) actually had separate "lunar overshoes." These were giant, blue-soled boots with deep, horizontal treads made of a material called Chromel-R (woven stainless steel). They were designed to provide traction and extra thermal protection against the 250°F lunar surface.

When it was time to leave, weight was the enemy. Every ounce of fuel mattered. So, Armstrong and Aldrin left the heavy overshoes—along with their cameras and portable life support backpacks—on the lunar surface.

The suit you see in the museum today is the "inner" pressure suit. The treads stay on the moon; the man came home.

21 Layers of Life Support

The complexity of the neil armstrong space suit is hard to wrap your head around. It wasn't just fabric. It was 21 layers of synthetic materials, neoprene rubber, and metalized polyester films.

- The Inner Layer: A liquid cooling garment that looked like blue long johns with "spaghetti tubing" sewn in. Water pumped through these tubes to keep the astronaut from overheating. Space is weird; even though it's "cold," you can't vent body heat in a vacuum. You'd literally boil in your own sweat without that water cooling.

- The Pressure Bladder: A rubber-coated nylon layer that held the oxygen in.

- The Outer Shell: This was made of Beta cloth. After the tragic Apollo 1 fire, NASA demanded a material that wouldn't burn. Beta cloth is essentially Teflon-coated glass microfibers. It can withstand 1,000°F.

The suit also featured a "valsalva device." It’s a tiny foam block inside the helmet. Why? Because you can’t scratch your nose or pop your ears inside a pressurized fishbowl. If Armstrong’s ears plugged up during descent, he’d lean his face forward and use that block to plug his nose so he could blow and equalize the pressure.

It's the small, human details that really make the engineering impressive.

The Current State of the Artifact

For a long time, the neil armstrong space suit was rotting. Not from neglect, but from its own chemistry. The neoprene rubber used in the 60s wasn't meant to last decades; it was meant to last for a mission. It started off-gassing and becoming brittle.

In 2015, the Smithsonian launched a "Reboot the Suit" campaign. They raised over $500,000 to basically build a high-tech climate-controlled display.

💡 You might also like: Graciosos stickers para whatsapp memes y por qué tu chat sigue siendo aburrido

Today, if you visit the National Air and Space Museum, the suit is kept in a case that mimics the lunar environment—minus the vacuum. It has its own dedicated ventilation system that pulls out the acidic gases the materials naturally produce.

It’s still stained, though. If you look closely at the knees and the shins, you’ll see grey smudges. That’s actual lunar dust. It's incredibly abrasive—like microscopic shards of glass—and it worked its way into the fibers of the Beta cloth. NASA tried to clean it back in the day, but that stuff is stuck for good.

Lessons from the A7L

Looking back at the neil armstrong space suit, there are some pretty clear takeaways for how we design for extreme environments today.

- Customization is King: We’ve moved toward modular suits now to save money, but for a mission that critical, the 64 individual body measurements taken for Armstrong's suit were what made it work.

- The "Soft" Approach Wins: You don't always need a titanium shell. Flexibility often provides better protection than rigidity.

- Weight Management: The "leave it behind" philosophy is still how we plan for Mars. If it isn't necessary for the ride home, it stays on the dirt.

If you’re interested in seeing the suit’s legacy, you can actually view a high-resolution 3D scan on the Smithsonian’s website. It allows you to see the individual stitches and the texture of the Chromel-R patches on the shoulders.

For anyone wanting to dive deeper into the technical side, the best next step is to look into the ILC Dover archives. They are still the primary contractors for NASA's space suits today, and their documentation on the transition from the A7L to the modern EMU (Extravehicular Mobility Unit) shows exactly how much—and how little—the technology has changed since 1969. You should also check out the "Destination Moon" exhibit at the National Air and Space Museum if you're ever in D.C.; seeing the lunar dust on the fabric in person puts the entire Apollo program into a perspective that photos just can't capture.