Math is weird. Honestly, most of us haven't touched a formal equation since high school, yet we deal with numbers every single day. One specific calculation—negative 3 times 3—seems to be a sticking point for anyone trying to refresh their memory on basic algebra or logic. It's a tiny problem. Just three characters and a symbol. But it carries a lot of baggage because it forces us to deal with the concept of "negativity" in a physical world that usually only counts things that exist.

Think about it this way. If you have three apples, you can see them. If you lose three apples, they're gone. But what does it actually mean to have a negative amount of something and then multiply that debt? That’s where the brain starts to itch.

The Absolute Basics: Calculating Negative 3 Times 3

Let’s just get the answer out of the way first. $$-3 \times 3 = -9$$.

It's straightforward. You take the number three, you triple it, and because one of those numbers started with a minus sign, the result keeps that minus sign. This is one of those fundamental laws of arithmetic that we’re taught in middle school, usually right around the time we start wondering when we'll ever use this in "real life."

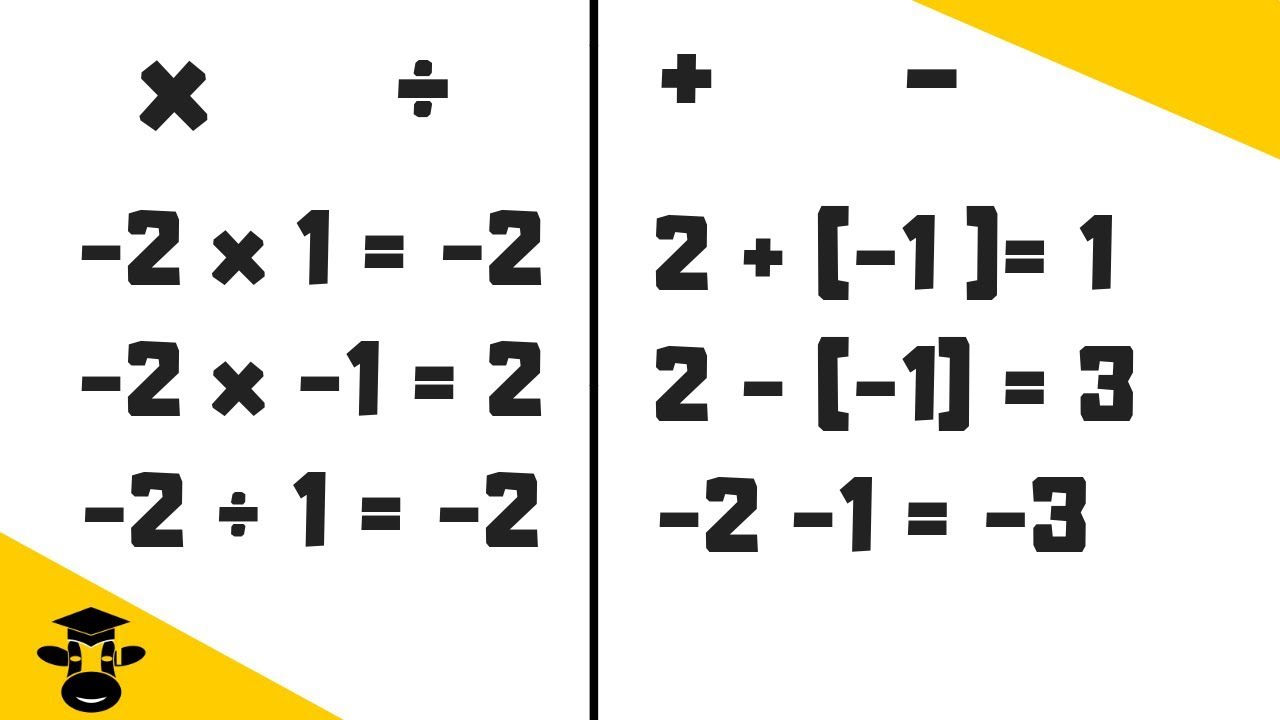

The rule is actually quite rigid. When you multiply a negative number by a positive number, the product is always negative. It doesn't matter which one comes first. You could have 3 times negative 3, and you'd still end up at negative 9. The signs are what dictate the outcome here, not the order of operations.

Why does this happen? Well, multiplication is basically just repeated addition. If you have negative 3 times 3, you are essentially saying "take negative three and add it to itself three times."

$$(-3) + (-3) + (-3) = -9$$

If you owe someone three dollars, and then you somehow manage to owe two other people three dollars each, you are now nine dollars in the hole. You don't magically end up with positive money just because you've tripled your debt. That would be a great way to run a bank account, but the universe doesn't work that way.

Visualizing the Number Line

Sometimes seeing is believing. If you imagine a long horizontal line with a zero in the middle, all your positive numbers live to the right. Your negatives live to the left.

✨ Don't miss: Find My iPhone on PC: What to Do When Your Phone Is Actually Gone

When you look at negative 3 times 3 on this line, you start at zero. You take a leap of three units to the left, landing on -3. Then you do it again. Now you’re at -6. One more jump? You’re sitting right on top of -9.

It’s a directional shift. The negative sign acts like a "turn around" command. It tells the math that we are moving away from the positive and deeper into the "less than zero" territory. This is why teachers often use the "walking" analogy. If you face the positive direction but walk backward, you’re going negative. If you do that for three steps, three times over, you’ve traveled nine steps in the wrong direction.

Common Misconceptions and Why They Happen

People mess this up all the time. Seriously.

The biggest culprit is the "double negative" rule. We’ve all had it drilled into our heads that "two negatives make a positive." In English, saying "I don't have no money" technically means you have money (though your grammar teacher might have something to say about it). In math, negative 3 times negative 3 is indeed positive 9.

But negative 3 times 3 only has one negative.

Because there isn't a second negative to "cancel out" the first one, the result stays negative. It’s a common mental shortcut that goes wrong. People see a minus sign and their brain automatically looks for its partner to flip it back to positive. If that partner isn't there, the negative stays.

There's also the confusion with exponents. This is a huge one in algebra classes.

- $-3^2$

- $(-3)^2$

These look identical to the untrained eye, but they are completely different. In the first one, the square only applies to the 3. You square the 3 to get 9, then slap the negative on at the end. Result? -9. In the second one, you are multiplying -3 by -3. Result? Positive 9. This subtle distinction causes more failed math tests than almost anything else. It’s all about the grouping.

Real-World Applications (Yes, They Exist)

You might think you’ll never need to calculate negative 3 times 3 outside of a classroom. You'd be surprised.

Finance is the big one. If a stock drops 3 points every day for 3 days, your total change is -9 points. Your portfolio isn't "positive 9" just because it happened multiple times. It’s a cumulative loss.

Engineering and physics use this too. Think about velocity. If "positive" is North and "negative" is South, and you are traveling at a velocity of -3 meters per second (meaning you’re headed South), where will you be in 3 seconds? You’ll be at -9 meters relative to your start.

Temperature is another great example. If the temperature drops 3 degrees every hour for 3 hours, the total change is -9 degrees. If it was 0 degrees to start with, you're now at -9. It's a simple way to track trends that move downward.

Why This Matters for Coding and Logic

If you’re getting into programming—whether it’s Python, JavaScript, or C++—the way a computer handles negative 3 times 3 is vital. Most modern programming languages follow the standard order of operations (PEMDAS/BODMAS).

However, if you are writing a script and you forget how the computer interprets a negative sign in front of a variable, you can end up with some nasty bugs. Computers are literal. They don't guess what you meant. If you tell a program to calculate the area of something but accidentally feed it a negative coordinate without proper absolute value handling, the math will break.

In data science, we see this with "weighting." If a specific data point has a negative weight of 3 and it appears 3 times in a dataset, its total impact on the final score is -9. This helps balance out positive outliers. It’s all about the "pull" of the numbers.

A Brief History of Negative Numbers

It's actually kind of wild to think that for a long time, mathematicians didn't believe in negative numbers. They thought they were "absurd."

The Ancient Greeks, for all their brilliance, basically ignored them. It wasn't until around 600 AD in India that mathematicians like Brahmagupta started formalizing rules for negatives, calling them "debts" as opposed to "fortunes." He was the one who really laid out that a debt times a fortune is a debt.

Europe took even longer to catch on. Even in the 1700s, some mathematicians were still skeptical. They couldn't wrap their heads around something being "less than nothing." Today, we take it for granted, but negative 3 times 3 represents a massive leap in human abstract thought. We learned how to quantify the absence of things.

Practical Steps for Mastering Directed Numbers

If you’re trying to help a kid with their homework or just want to sharpen your own brain, don't just memorize the rules. Internalize the logic.

First, check the signs. Before you even look at the numbers, look at the symbols. One negative? The answer is negative. Two negatives? The answer is positive. Zero negatives? Obviously positive.

Second, do the "raw" math. Multiply 3 by 3 to get 9. Then apply the sign you determined in step one. This prevents "mental overload" where you try to do too many things at once.

Third, use a physical analogy. Think of a elevator. If you go down 3 floors (a negative move) and you do that 3 times, you are 9 floors below where you started.

Most mistakes with negative 3 times 3 aren't because people don't know what 3 times 3 is. It's because they lose track of the "direction" of the number. Slowing down for a split second to recognize that a single negative always wins out in multiplication will save you a lot of headache.

Next time you see a negative number in a budget spreadsheet or a coding project, don't let it intimidate you. It’s just a direction. It’s just a way of saying "this way, not that way." Once you get comfortable with the flip-flop of signs, the rest of algebra starts to feel a lot less like a chore and a lot more like a puzzle you actually know how to solve.