The J train is the workhorse of North Brooklyn and Lower Manhattan, but let's be real: looking at the J line subway map for the first time is a total headache. It’s brown. It zig-zags. It does that weird skip-stop thing that leaves tourists stranded on platforms in the middle of July heat.

You’ve probably stood at Essex Street or Broadway Junction, staring at those tangled lines, wondering why the train just blew past your stop. It’s frustrating. It's confusing. But honestly, once you get the rhythm of the Nassau Street Local (and Express), it’s one of the most efficient ways to cut through the city.

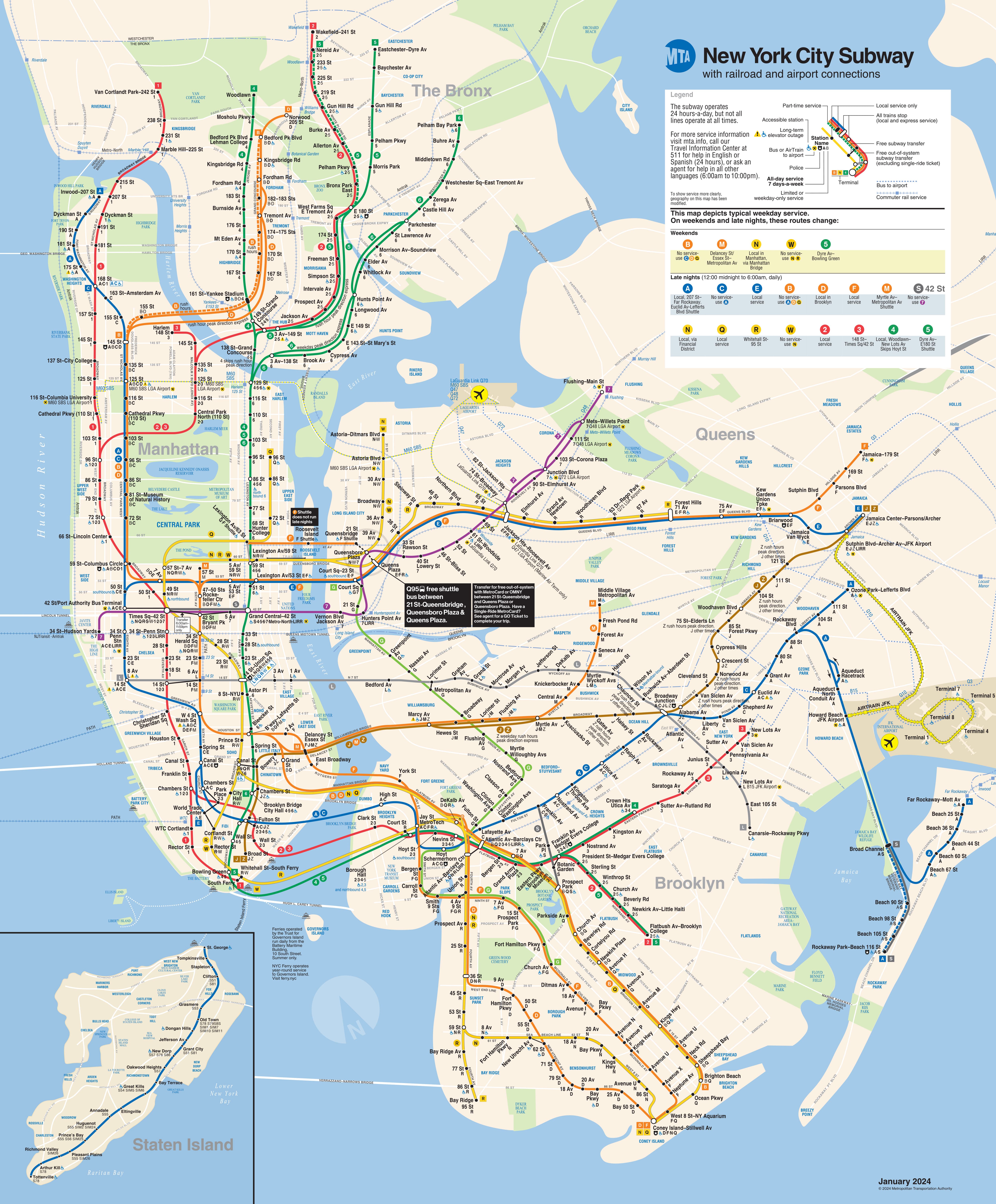

The J line, officially known as the Nassau Street Local, runs from Broad Street in Manhattan all the way to Jamaica Center–Parsons/Archer in Queens. It’s a long haul. Along the way, it hits some of the most gentrified—and some of the most historically gritty—neighborhoods in the five boroughs. If you're trying to master the J line subway map, you have to understand more than just the dots on the page; you have to understand the timing.

The Skip-Stop Chaos: J vs Z

Most people look at the map and see the J and the Z running together like twins. They aren't. Not exactly. During rush hours—specifically peak directions like Manhattan-bound in the morning—the J line enters "skip-stop" mode.

This is where the map becomes a bit of a liar if you aren't paying attention to the icons. Some stations are "J" stops, some are "Z" stops, and the big ones are both. If you're standing at Hewes Street at 8:30 AM, a J train might fly right past you while a Z train pulls in. Or vice versa. It depends on the color of the circle on the map.

Basically, the J and Z share the BMT Eastern Division Line. Between Myrtle Avenue and Broadway Junction, they alternate. It’s a relic of an older era of transit planning designed to speed up the commute for people coming all the way from Jamaica. If you’re a local, you know the pain of seeing your train approach, only to realize it's the "wrong" letter for your specific small station.

Reading the Brown Line: Key Transfer Points

When you track the J line subway map from West to East, the density of the city changes drastically. It starts at Broad Street, deep in the Financial District. This is the end of the line. There’s no loop here; the train literally just stops and turns around.

👉 See also: Why The Capital Hotel Knightsbridge is London's Best Kept Secret

From there, you hit Fulton Street. This is the "everything" hub. You can get to the 2, 3, 4, 5, A, C, and R. It’s a labyrinth. If you’re transferring here, give yourself ten minutes. Seriously. The walk underground feels like a hike through a concrete cave.

Then comes Chambers Street. It’s old. It’s dusty. It looks like it hasn't been painted since the 1970s. But it’s vital because it connects you to the Brooklyn Bridge-City Hall 4, 5, and 6 trains.

Once you cross the Williamsburg Bridge—which offers one of the best free views of the city, by the way—you land in Brooklyn. Marcy Avenue is the first stop. It’s where the hipsters get off. If you’re heading to South Williamsburg, this is your spot. But be warned: the platform is narrow and gets incredibly crowded during the evening rush.

Why the J Line Map is Different

Most NYC subway lines run North-South. The J is different. It’s one of the few lines that feels like it’s moving laterally across the "bulge" of Brooklyn.

Broadway Junction: The Great Connector

If there is one place on the J line subway map that strikes fear into the hearts of newcomers, it’s Broadway Junction. It’s an elevated station, soaring high above the street. You have the J, the Z, the A, the C, and the L all converging here.

It is loud. It is windy. It is beautiful in a very industrial, "Old New York" kind of way. From here, the J continues into East New York and then climbs into Queens. This stretch is almost entirely elevated. You aren't in a tunnel anymore; you're looking into people’s second-story windows and over the rooftops of auto body shops.

The Queens Stretch

As the line moves into Woodhaven and Richmond Hill, the stations start to look identical. 75th St-Elderts Lane, 85th St-Forest Parkway, Woodhaven Blvd. The map shows them as a straight shot, but the reality is a slow crawl through dense residential neighborhoods.

Finally, you hit the Archer Avenue Extension. This is where the train goes back underground. It ends at Jamaica Center. If you’re trying to get to the JFK AirTrain, don’t stay on until the last stop. You need to get off at Sutphin Blvd–Archer Av–JFK Airport. It’s a common mistake. People stay on until the end, realize they’ve gone too far, and have to double back. Don't be that person.

👉 See also: Weather in Baltimore Maryland: What Most People Get Wrong

The Secret History of the Nassau Street Line

The J line isn't just a commute; it’s a survivor. Back in the day, this line used to connect to the elevated tracks on the Brooklyn Bridge. You could take a train from Jamaica and end up at Park Row in Manhattan.

The current J line subway map is a stripped-down version of what used to be a massive network of elevated lines. When the city started tearing down the "els" in the mid-20th century, the J (then known as the 15) was one of the few that stayed because the neighborhoods it served—like Bushwick and Woodhaven—didn't have underground alternatives.

This explains why the J feels so different from the 4, 5, or 6. It’s an "overground" experience for more than half its journey. You see the weather. You see the sun. You see the skyline. It makes the commute feel less like being a mole and more like being a part of the city.

Common Misconceptions About the J

One of the biggest myths is that the J is "the slow way" to get to Queens. While the E train is definitely faster for getting to Midtown, the J is often superior for getting to Lower Manhattan. If you’re in Richmond Hill and need to be at Wall Street, the J is your best friend.

Another misconception? That the Z train runs all day. It doesn't. Check the timetable. The Z is a ghost train that only appears during the height of rush hour. If you see a Z on the J line subway map and it's 2 PM on a Tuesday, ignore it. It’s not coming.

Then there’s the weekend service. The MTA loves to do track work on the J. Since it’s an elevated line, the structures need constant painting and steel replacement. On many weekends, the J might terminate at Myrtle Avenue or Broadway Junction, with a shuttle bus (the dreaded "free shuttle") taking you the rest of the way. Always, always check the MYmta app before you rely on the map on a Saturday morning.

Survival Tips for the J Train

If you're using the J line subway map to plan a trip, keep these practical realities in mind:

- The Williamsburg Bridge climb: The train slows down significantly when going over the bridge. If you're running late, that five-minute crawl over the East River will feel like an hour.

- The "M" connection: At Myrtle Avenue, the M train branches off toward Middle Village. The J and M share tracks from Essex Street to Myrtle. Make sure you’re on the right one before you leave the platform.

- Noise levels: Because it's an elevated line, the J is loud. Like, "can't hear your own thoughts" loud. If you’re on a phone call, it’s going to drop or become unintelligible the second you hit the elevated tracks.

- Summer heat: Elevated stations have no AC. Manhattan underground stations (mostly) have some airflow. The J platforms in Brooklyn can get up to 100 degrees in August. Stay hydrated.

The Future of the J Line

There’s a lot of talk about modernizing the J. We’re seeing more of the "New Train Cars" (the R160s and R179s) which have better maps and clearer announcements. The days of the muffled, garbled conductor voice saying "Stand clear of the closing doors" are slowly fading.

The J line subway map itself hasn't changed much in decades, but the neighborhoods around it are shifting. As East New York undergoes rezoning and Jamaica continues to develop as a commercial hub, the J is becoming more crowded. It’s no longer the "quiet" line.

Actionable Steps for Your Next Trip

Stop just looking at the colors and start looking at the symbols.

- Check the Circles: If the station on the map is a full circle, the J stops there all the time. If it’s a split circle or has a letter next to it, check the time.

- Use the Sutphin Blvd Transfer: If you are heading to JFK, this is the most underrated transfer in the city. It’s usually less crowded than the E train at the same station.

- Watch the "Express" signs: In the afternoon, some J trains run express in Brooklyn. If you’re trying to get to a local stop like Halsey Street or Kosciuszko Street, make sure you aren't on a train that’s about to skip six stops in a row.

- Download a Live Map: The paper maps in the station don't show "General Orders" (construction). Use the live digital maps to see if the J is actually running to Manhattan before you swipe your OMNY.

The J line is a massive, complex artery of New York City. It isn't always pretty, and it definitely isn't always on time, but it has a character that the shiny underground lines lack. Learn the skip-stop, watch the bridge views, and you'll find it's one of the most reliable ways to navigate the soul of the city.