If you’ve ever stared at a calculator and wondered why the heck there’s a button for "ln" and another for "log," you aren’t alone. It’s weird. Most of us learn math as a series of chores—move the decimal, carry the one, solve for $x$. But when you get to the relationship of natural log to e, you’re actually touching the internal wiring of how the universe grows. It’s not just homework. It’s the math of interest rates, radioactive decay, and even how fast a population of bacteria takes over a petri dish.

Most people think of $e$ as just another annoying number like $\pi$. It’s $2.71828...$ and it goes on forever. But honestly? It’s more than a number. It’s a rate. Specifically, it’s the maximum possible result of compounding 100% growth continuously. If you have $1 and it grows at 100% interest per year, and you compound it every single microsecond, you end up with $e$.

The natural log, written as $\ln(x)$, is the "How long did that take?" part of the equation. It's the inverse. If $e$ is the engine driving the car forward, the natural log is the odometer looking backward to see how far you've come.

Why Natural Log to e is the Inverse You Actually Need

We’re used to base-10. We have ten fingers. Our entire currency is built on tens. So why is the "natural" log based on this messy $2.718$ number?

Because nature doesn't grow in steps.

Think about a tree. It doesn’t wait until December 31st to suddenly sprout two inches of height in a single "compounding" event. It grows every second of every day. That’s continuous growth. When mathematicians like Leonhard Euler—the guy $e$ is named after—started looking at how things actually change in the real world, they realized that base-10 was clunky. It didn't fit the curves of reality.

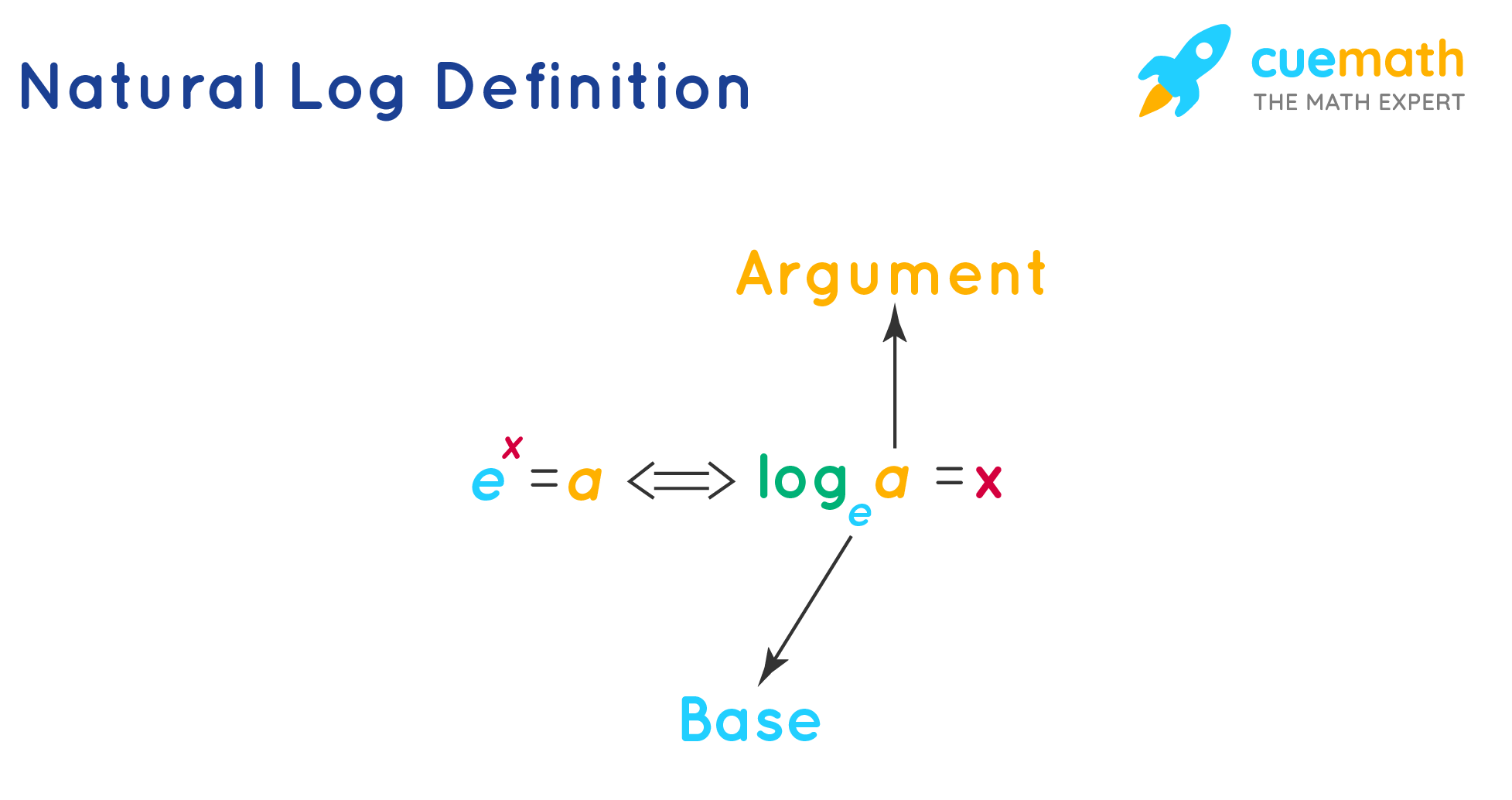

The relationship between natural log to e is defined by a simple but powerful identity:

$$\ln(e^x) = x$$

And conversely:

$$e^{\ln(x)} = x$$

It’s a perfect mirror. If you have a growth process described by $e$, and you want to "undo" it to find the time or the rate, you use the natural log. It's like the relationship between square roots and squaring a number, just much more useful for anything involving time and change.

The Secret of Compound Interest and Reality

Let's get into the weeds for a second. Imagine you're looking at a bank account.

If your money is compounding continuously, the formula is $A = Pe^{rt}$. You’ve probably seen that in a textbook and immediately forgotten it. $P$ is your starting cash, $r$ is the rate, and $t$ is time. If you want to know when your money will double, you’re trying to solve for $t$.

This is where the natural log to e transition happens. You set $A$ to $2P$, cancel out the $P$s, and you’re left with $2 = e^{rt}$. How do you get that $t$ down from the ceiling? You drop a natural log on it. $\ln(2) = rt$. Since $\ln(2)$ is roughly $0.693$, you suddenly have a way to calculate growth in your head.

💡 You might also like: Meta Devices Facebook Explained: What Most People Get Wrong

That’s actually where the "Rule of 72" comes from in finance. Investors use it to estimate doubling time. They use 72 because it has more divisors, but the "real" number is $69.3$, which comes directly from the natural log of 2.

Logarithms Aren't Just for Scientists

You use these every day without realizing it. Your ears are logarithmic. If you’re at a rock concert and the band turns the volume up, the actual physical pressure of the sound waves might double, but your ear doesn't hear it as "twice as loud." It hears it as a small step up.

The Richter scale for earthquakes? Logarithmic.

pH levels in your pool? Logarithmic.

But why use $e$ instead of 10?

Calculus is the real reason. In the world of derivatives—which is just a fancy way of saying "how fast is this changing right now"—the function $f(x) = e^x$ is the only function that is its own derivative. It’s the ultimate "what you see is what you get." The rate of change is the value itself.

If you try to do calculus with $\log_{10}$, you end up with messy extra constants that clutter the page. It’s like trying to measure a rug in "donkey lengths" instead of meters. You can do it, but why would you? The natural log to e connection keeps the math clean. It’s the "native language" of change.

Common Mistakes People Make with ln and e

Most students—and honestly, a lot of adults who haven't looked at a graph in a decade—treat $\ln$ as a variable. It’s not. It’s an operator. It’s an action.

Thinking $\ln(a+b) = \ln(a) + \ln(b)$. It doesn't. This is a classic trap. The log of a sum is not the sum of the logs. However, the log of a product is the sum of the logs: $\ln(ab) = \ln(a) + \ln(b)$. This property is why logs were invented in the first place—to turn terrifying multiplication problems into simple addition.

Forgetting the Domain. You can't take the natural log of a negative number. At least, not without getting into complex numbers and imaginary units ($i$), which is a whole other rabbit hole. If you try to ask "How much time does it take for my money to grow to negative $500?" the math just breaks. It’s impossible.

👉 See also: YouTube Sorry There Was an Error Licensing This Video: How to Actually Fix It

Mixing up $\log$ and $\ln$. On most scientific calculators, $\log$ is base-10 and $\ln$ is base-$e$. If you use the wrong one, your answer will be off by a factor of about $2.3$. That’s the difference between a successful engineering project and a bridge falling into a river.

How to Solve Natural Log to e Equations Like a Pro

If you’re staring at an equation like $5e^{2x} = 20$, don't panic. It's a three-step dance.

First, isolate the $e$ part. Divide by 5. Now you have $e^{2x} = 4$.

Next, apply the natural log to both sides. This "cancels" the $e$ on the left. You’re left with $2x = \ln(4)$.

Finally, divide by 2. $x = \ln(4) / 2$.

You’re done. You just used the fundamental property of natural log to e to solve for an unknown exponent. This is exactly how scientists determine the age of a bone using Carbon-14 dating. They know how much Carbon-14 is left ($A$), they know the starting amount ($P$), they know the decay rate ($r$), and they use the natural log to find the time ($t$).

The Intuition: Looking at the Curve

If you graph $y = e^x$, it shoots up like a rocket. It starts slow and then goes vertical.

✨ Don't miss: Percy Spencer: The Radar Scientist Who Accidentally Revolutionized Your Kitchen

If you graph $y = \ln(x)$, it does the opposite. It climbs quickly at first and then flattens out, trudging along slowly.

They are reflections of each other across the line $y = x$. This symmetry is beautiful. It means that for every "action" of exponential growth, there is a "reaction" of logarithmic measurement.

In the 1600s, John Napier spent decades calculating log tables by hand. He did this because he wanted to help astronomers calculate the movements of planets without spending their whole lives doing long multiplication. He basically built a manual version of the natural log to e relationship before we even really understood what $e$ was. He knew there was a shortcut to the stars.

Real World Insight: Why $e$ is Everywhere

It’s in the way a rope hangs between two poles (the catenary curve).

It’s in the probability distribution of heights in a population (the Bell Curve).

It’s even in the "Secretary Problem" in optimal stopping theory, which tells you when to stop looking for a romantic partner or a new employee to get the best possible result. (The answer is usually after you've seen $1/e$, or about 37%, of the candidates).

The connection is inescapable. Whether you’re a coder optimizing an algorithm or a nurse calculating how long a medication stays in a patient's bloodstream, you're dancing with $e$.

Actionable Steps for Mastering the Natural Log

If you want to actually get good at using this, stop trying to memorize formulas and start focusing on the "undo" principle.

- Practice the Conversion: Whenever you see $e^a = b$, immediately write it as $\ln(b) = a$. Do it until it’s a reflex.

- Visualize the Growth: Remember that $e$ is about the result of growth, and $\ln$ is about the time required. If someone says "It grew by $e^3$," think of it as "It grew for 3 units of time at 100% continuous interest."

- Check Your Calculator: Find the $\ln$ and $e^x$ keys. Notice they are usually the same button, just shifted. That’s not an accident. It’s a reminder that they are two sides of the same coin.

- Use the Change of Base Formula: If you ever need to find a log in a weird base like base-7, just use natural logs: $\log_7(x) = \ln(x) / \ln(7)$. It works every time.

The relationship of natural log to e is one of the few things from high school math that actually stays relevant. It describes the heartbeat of the world. It’s the difference between a static, dead view of numbers and a dynamic, living view of change. Once you see the link, you can't unsee it. It's everywhere.