It feels like the world is falling apart. You turn on the news and see a "once-in-a-century" flood in Europe, only to see another one hit a different continent two weeks later. It's exhausting. But when you actually dig into the natural disaster statistics by year, the picture isn't just about "more" disasters; it's about how much more they cost us and how specifically our infrastructure is failing.

We aren't just imagining it. The numbers are legitimately weird.

According to the Emergency Events Database (EM-DAT) managed by the Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters (CRED), the frequency of reported disasters has skyrocketed since the 1960s. Back then, we were looking at maybe 100 recorded events globally per year. By the early 2000s, that number jumped to over 400. People argue about this, of course. Some skeptics say we’re just better at reporting them now because everyone has a smartphone and satellite internet. While that’s partially true, it doesn't explain the massive spike in "billion-dollar disasters" that organizations like NOAA track so religiously.

What Natural Disaster Statistics by Year Actually Reveal About Our Safety

The 2020s have been a brutal wake-up call. If you look at 2023, for example, the world saw 398 notable natural disaster events. That sounds like a lot, but the real kicker is the economic toll. We’re talking about $380 billion in global economic losses in a single year.

Most of that isn't even insured. That’s the scary part for the average person. When a hurricane hits, or a wildfire sweeps through a suburb, a huge chunk of that recovery falls on the taxpayer or the individual. In the United States alone, 2023 set a record with 28 separate billion-dollar weather and climate disasters. Think about that. Almost every two weeks, something happened that cost at least a billion dollars.

Floods and Storms: The Constant Heavy Hitters

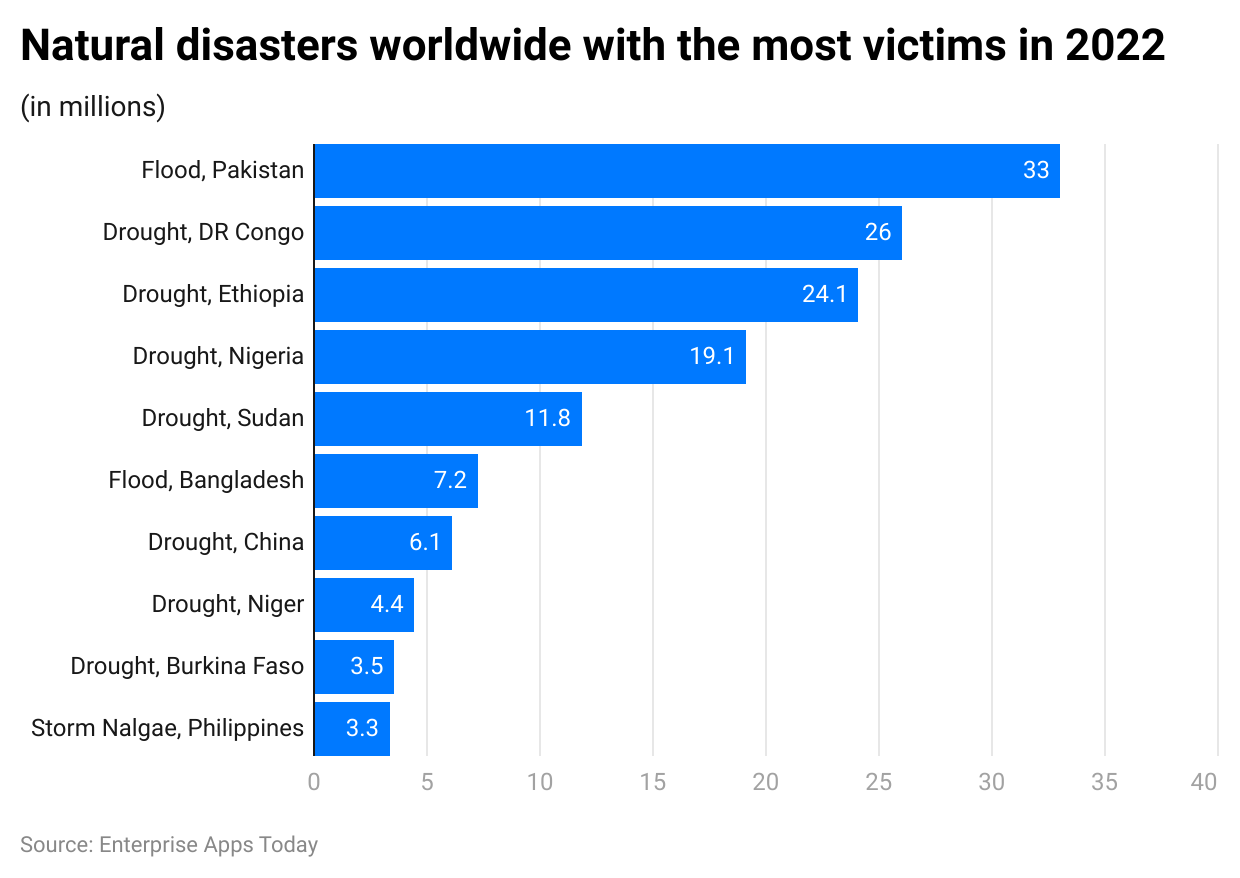

Flooding is basically the "silent killer" of global economies. It happens everywhere. In 2022, the floods in Pakistan were so catastrophic they covered a third of the country. Over 33 million people were affected. When you look at the natural disaster statistics by year for the last decade, hydrological events—floods and landslides—consistently make up about 40% to 50% of all recorded disasters.

It isn't just rain. It's "training" storms where cells follow each other like train cars, dumping a month's worth of water in three hours. Our sewers can't handle it. Our basements definitely can't handle it.

The Heat Paradox

Here is something weird: Heatwaves are technically the deadliest natural disasters, but they are the most underreported in the "event" stats. If an earthquake kills 1,000 people, it's a headline. If a heatwave in Europe kills 15,000 elderly people over three weeks, it's often buried in public health reports months later.

👉 See also: Why are US flags at half staff today and who actually makes that call?

In 2003, a European heatwave killed upwards of 70,000 people. We saw similar spikes in 2022 and 2023. Yet, because a heatwave doesn't "knock down" a building, we tend to treat it differently in the data. We shouldn't. The mortality rates in these years show that temperature extremes are becoming a primary driver of disaster-related deaths, even as our ability to predict hurricanes improves.

Why 2024 and 2025 Changed the Conversation

Honestly, 2024 was a mess. Between the erratic behavior of the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) and record-breaking sea surface temperatures, the atmosphere was basically on steroids.

Meteorologists like Jeff Masters have pointed out that we are seeing "rapid intensification" in hurricanes more often. This is a specific term. It means a storm jumps from a Category 1 to a Category 4 in less than 24 hours. That ruins evacuation plans. It makes the natural disaster statistics by year look more volatile because the lead time for safety measures is shrinking.

- Hurricane Beryl in 2024 was the earliest Category 5 storm on record.

- The 2024 wildfire season in Canada started earlier and stayed "zombie" style through the winter.

- Brazil faced floods in Rio Grande do Sul that basically wiped out entire logistical chains for months.

These aren't just points on a line graph. They are systemic shocks.

The Economic Reality of Disaster Data

If you’re looking for a silver lining, it’s that fewer people are dying from disasters than they did 100 years ago. In the 1920s, a bad drought or flood could kill millions through famine and lack of warning. Today, thanks to the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) and better early warning systems, the death toll has dropped by about 3x since the 1970s.

But the costs? They are going the other way.

We are building more expensive stuff in dangerous places. We build glass condos on beachheads and wooden suburbs in fire-prone forests. So, while we are getting better at running away, we are getting worse at protecting our wealth. The insurance industry is freaking out. You might have noticed companies pulling out of Florida or California entirely. That is the direct result of these natural disaster statistics by year becoming too predictable for insurers to make a profit.

✨ Don't miss: Elecciones en Honduras 2025: ¿Quién va ganando realmente según los últimos datos?

Geopolitical Displacement

Climate migration is a term people throw around a lot, but the stats back it up. The Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC) tracks this. In many years, more people are displaced by natural disasters than by war.

In 2023, roughly 26.4 million people were displaced by weather-related disasters. This creates a massive ripple effect in urban planning and international relations. When a storm hits the Philippines or a drought kills crops in the Horn of Africa, people move. They have to.

Breaking Down the Decades

Let’s look at how the frequency has shifted.

In the 1980s, we averaged about 150 disasters per year.

In the 1990s, that crept up toward 250.

From 2000 to 2019, the average stayed around 350 to 400.

It seems to have plateaued in terms of "raw number of events," but the intensity of those events is what’s shifting. We are seeing more "secondary perils." These are things like hail, flash floods, and wildfires that aren't quite "hurricanes" but happen so often they bleed the economy dry.

Earthquake Anomalies

Earthquakes don't care about climate change, obviously. They follow the rhythm of the tectonic plates. However, when an earthquake hits a vulnerable area—like the Turkey-Syria border in 2023—the disaster statistics spike massively. That single event killed over 50,000 people.

This is an important distinction: Weather disasters are increasing in frequency, but geophysical disasters (earthquakes, volcanoes) remain relatively steady. They just cause massive "steps" in the death toll data when they happen to hit a populated, poorly constructed city.

🔗 Read more: Trump Approval Rating State Map: Why the Red-Blue Divide is Moving

Lessons from the Numbers

So, what do we do with all this? Staring at a spreadsheet of destruction is depressing unless you use it to change how you live.

First, the "100-year flood" terminology is dead. It’s misleading. A 100-year flood just means there is a 1% chance of it happening in any given year. You can have three of them in a row. Don't buy a house based on that old phrasing. Look at the elevation maps yourself.

Second, insurance is changing. If you live in an area where the natural disaster statistics by year show an upward trend in hail or wind damage, your premiums will never go back down. It’s a permanent shift.

Third, community resilience matters more than individual prepping. The data shows that towns with "micro-grids" for electricity and decentralized water systems bounce back weeks faster than those relying on one giant power plant.

Actionable Steps to Take Right Now

Stop thinking about disasters as "accidents" and start thinking about them as "scheduled maintenance" for the planet that you need to be ready for.

- Audit Your Insurance: Don't just look at the monthly cost. Check for "actual cash value" vs. "replacement cost." In a disaster, you want replacement cost. Also, check if you have a separate deductible for wind or hail—many people get burned by this.

- The 72-Hour Rule is Now a 7-Day Rule: Emergency management agencies used to say you need three days of supplies. With the supply chain issues we've seen in recent years, you really need a week. Clean water is the first thing to go. Get a high-quality gravity filter.

- Digitize Everything: The statistics show that the biggest hurdle for disaster victims isn't just the physical damage; it's the bureaucracy. Having your deeds, IDs, and insurance policies on a password-protected cloud drive can save you months of headaches.

- Check the Hazard Maps: Use tools like Risk Factor or the FEMA Flood Map Service Center. Don't trust the real estate listing. They are often using outdated data.

- Hardening Your Home: Small things like "hurricane straps" for your roof or clearing brush 30 feet from your house can be the difference between a total loss and a minor insurance claim.

The data is clear: the environment is getting more energetic. We are living in a high-energy era of history. Whether it's the warming oceans or the way we build our cities, the natural disaster statistics by year are a roadmap. They tell us exactly where we are vulnerable. We just have to be smart enough to read them.

For anyone tracking these trends, the most reliable real-time data comes from the NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI) for US-based stats and the Munich Re "NatCatSERVICE" for global economic insights. Keeping an eye on these once a year—usually around January when the previous year's totals are finalized—is the best way to stay informed without falling into the trap of doomscrolling. Knowledge is the only real antidote to the anxiety these numbers produce.