You’ve probably seen them. Those colorful, jagged maps floating around social media or tucked into the back of old history textbooks. They usually show neat, colorful blocks labeled "Sioux," "Apache," or "Cherokee," as if the entire continent was divided up like a giant jigsaw puzzle with hard plastic borders. Honestly? Those maps are mostly lying to you.

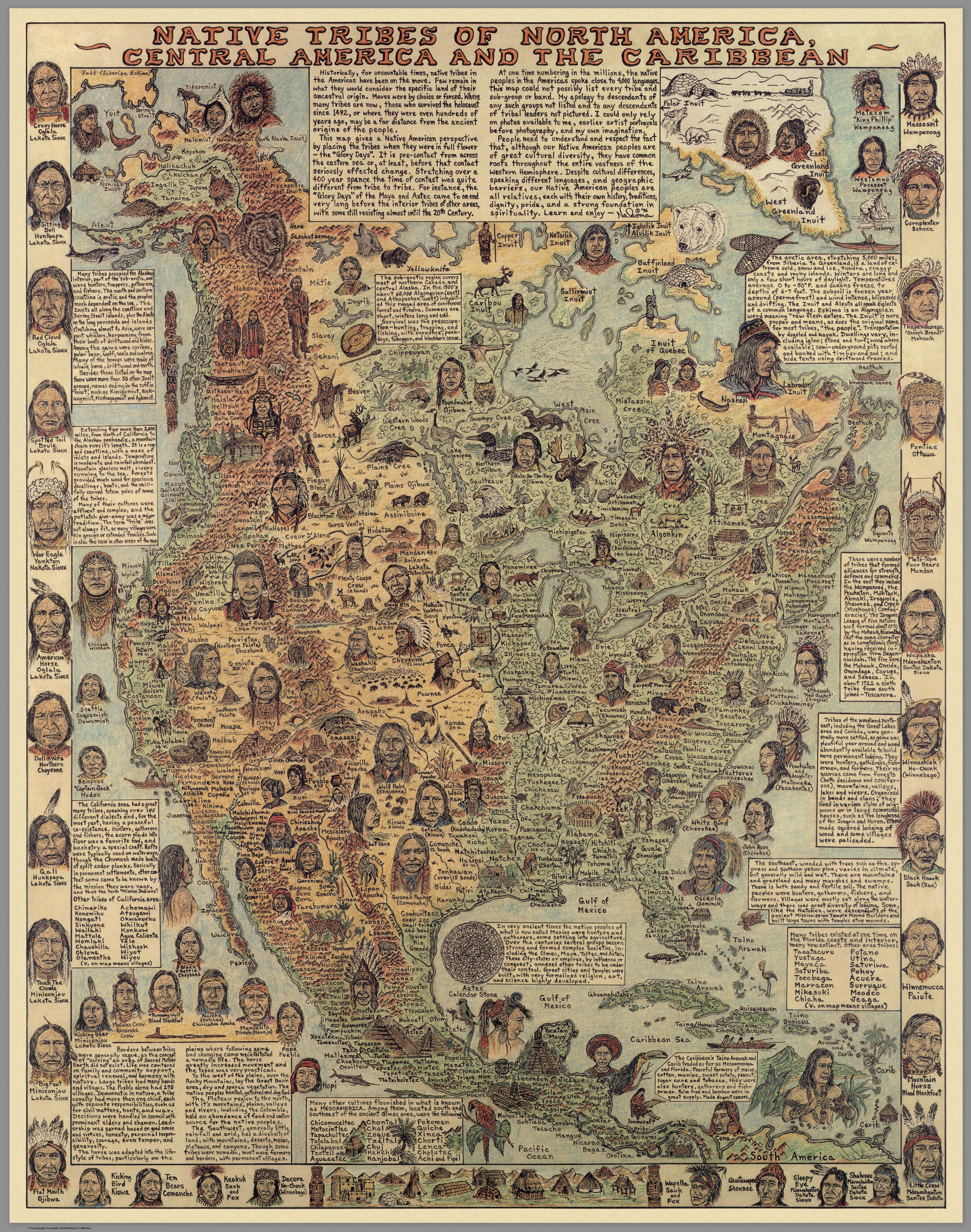

History is messy. Geography is messier. When we look at a native tribes map north america, we aren’t just looking at geography; we are looking at a snapshot of thousands of years of movement, diplomacy, and survival. Most people think of these boundaries as fixed lines in the sand, but for the Indigenous peoples of this continent, "borders" didn't really work like that. It was more about use-rights, seasonal cycles, and overlapping relationships.

If you want to understand the real layout of North America before—and after—European contact, you have to throw away the idea of a static map. Real life was fluid. People moved.

The Problem With Your Standard Native Tribes Map North America

The biggest mistake digital maps make is trying to freeze time. They pick a year—usually somewhere around 1492 or maybe 1800—and pretend everything was still. It wasn't. Populations shifted constantly. For instance, the Lakota weren't always the masters of the Great Plains. They actually migrated from the Great Lakes region, pushed westward by conflict and the lure of the buffalo. If you look at a native tribes map north america from 1500, you’ll find them in a completely different spot than a map from 1850.

There's also the issue of "empty space." Maps hate a vacuum. Cartographers feel this weird urge to color in every single square inch of the continent. But large swaths of North America were shared hunting grounds. Two or three different nations might use the same valley depending on the time of year. A map that gives that valley one single color is fundamentally inaccurate. It erases the complexity of Indigenous diplomacy.

Aaron Carapella, a self-taught Cherokee genealogist, spent years trying to fix this. He created maps that didn't just show "tribes," but used the names the people called themselves—their endonyms. Instead of "Navajo," his maps say "Diné." Instead of "Iroquois," they say "Haudenosaunee." This shift in language changes how you view the map entirely. It stops being a museum exhibit and starts being a record of living civilizations.

The Linguistic Mosaic

Language is usually the best way to categorize these maps, but even that gets tricky. North America was home to hundreds of distinct languages grouped into several massive families.

- Algonquian: This group covered a massive stretch from the Atlantic coast all the way to the Rockies. Think Powhatan, Blackfoot, and Ojibwe.

- Siouan: Not just the Sioux, but also the Mandan and the Osage.

- Athabaskan: This is wild because it includes the Dene in the far north of Canada and the Apache and Navajo in the desert Southwest.

Imagine the sheer distance between Alaska and Arizona. Now imagine people in both places speaking languages that share a common root. That’s the kind of scale we’re talking about. It’s like finding out everyone in Norway and everyone in Italy speaks a dialect of the same tongue. It hints at massive ancient migrations that most schoolbooks completely ignore.

Why "Native Land" Changed the Mapping Game

If you’ve ever Googled a native tribes map north america, you’ve likely landed on Native-Land.ca. It’s a Canadian-led project that basically revolutionized how we visualize Indigenous territories online. Victor Temprano, the founder, didn't want to create a "perfect" map because he knew a perfect map of Indigenous land is impossible.

👉 See also: Verheyden Funeral Home Mack Avenue: What Most People Get Wrong About Planning a Service

Instead, the site uses overlapping shapes. When you search for a city like Chicago or Seattle, the map doesn't just give you one name. It shows you the layers. It shows the Potawatomi, the Odawa, and the Ojibwe (the Council of the Three Fires) all occupying the same general space. This is a huge deal. It acknowledges that multiple groups lived, traded, and existed in the same areas simultaneously.

It’s not just about who was there first. It’s about who is still there. Many modern maps fail to show the transition from ancestral lands to modern reservations. They treat the "native tribes map north america" as a relic of the past. But you can't understand the map of Oklahoma without understanding the "Trail of Tears" and the forced relocation of the Five Civilized Tribes from the Southeast. The map changed because of policy, violence, and law.

The Great Basin and the "Invisible" Tribes

Some areas are much harder to map than others. The Great Basin—think Nevada, Utah, and parts of California—was home to the Shoshone, Paiute, and Ute peoples. Because these groups were often mobile and lived in smaller family units to adapt to the arid environment, colonial mapmakers often just labeled the whole area as "Unexplored" or grouped everyone together under one name.

This erasure had real-world consequences. If you aren't on the map, you don't have rights. At least, that was the colonial logic. Mapping became a tool of conquest. By drawing a line and saying "This is British territory" or "This is French territory," Europeans ignored the thousands of years of Indigenous land management that had already defined those borders.

Cultural Areas vs. Political Borders

Anthropologists usually cheat. Since mapping every individual village is impossible, they divide North America into "Cultural Areas." This is why you see maps labeled:

- The Northwest Coast: Famous for totem poles, salmon-rich rivers, and complex social hierarchies (Haida, Tlingit).

- The Southwest: Known for permanent adobe structures and advanced irrigation (Pueblo, Hopi).

- The Eastern Woodlands: The land of the longhouse and the wigwam, where the environment was lush and the political structures were incredibly sophisticated.

But even these categories are sort of "Native History Lite." They help us organize information, but they can flatten the differences between tribes. A Mohawk person and a Wampanoag person both lived in the Eastern Woodlands, but their lives, languages, and political alliances were worlds apart.

The Role of Trade Networks

If you could see a map of North America in 1000 AD, it wouldn't look like a bunch of isolated villages. It would look like a spiderweb. The "Mississippian Culture," centered around the massive city of Cahokia (near modern-day St. Louis), had a trade network that reached almost every corner of the continent.

Archaeologists have found shark teeth from the Gulf of Mexico in the Great Lakes. They’ve found obsidian from the Rockies in Ohio. A real native tribes map north america should include these highways of commerce. These weren't isolated people; they were connected by thousands of miles of trails and waterways. They knew who their neighbors were, and they knew who lived three weeks' travel away.

How to Use These Maps Today

So, you’re looking at a map. Maybe you want to know whose land you’re standing on, or maybe you’re doing a genealogy project. Don't just look for one name. Look for the "why" behind the location.

Maps are tools, but they can also be weapons of erasure. When you look at a modern map of the United States or Canada, the Indigenous presence is often reduced to tiny dots or shaded squares representing reservations. This is a massive distortion. The entire continent is "Native land" in a historical and legal sense, regardless of who holds the deed today.

Practical Steps for Researching Indigenous Geography

If you are trying to find accurate information, don't stop at the first Google Image result. Most of those are oversimplified.

- Check the Source: Is the map made by an Indigenous organization or a university? Academic maps from places like the Smithsonian are generally more reliable than random Pinterest graphics.

- Look for Overlaps: If a map shows hard, thin lines between tribes, be skeptical. Real tribal boundaries were often "buffer zones" or shared resources.

- Cross-Reference with Treaties: If you’re looking at a map from the 1800s, find the corresponding treaty. Most maps from that era show what the government wanted the borders to be, not necessarily where people actually were.

- Use Living Resources: Sites like Native-Land.ca or the Tribal Nations maps created by Aaron Carapella offer a more nuanced, "living" view of the continent.

- Consult Tribal Websites: Many nations, like the Osage or the Cherokee, have their own cultural preservation offices with maps they’ve vetted themselves.

The most important thing to remember? The map is not the territory. A native tribes map north america is a way for us to start a conversation about history, but it’s never the final word. The people represented on those maps are still here, and their connection to the land hasn't been erased just because the colors on a map changed.

Start by identifying the specific nations in your immediate area. Don't just learn the name; look into their specific history of movement. Did they always live there? Were they moved there by the federal government? Understanding that movement is the key to seeing the map for what it really is: a story of resilience rather than just a collection of names on a page. Reach out to local tribal cultural centers if you're looking for deep-dive historical data—they are the ultimate authorities on their own geography.