History books usually paint a pretty lopsided picture. You've probably seen the classic imagery: buckskin-clad warriors standing on a ridge, silently watching a wooden ship crest the horizon. It’s dramatic. It’s also mostly a caricature. When we talk about Native Americans in Colonial America, we’re not talking about a monolith or a group of people just "waiting" to be colonized. We’re talking about sophisticated political entities, massive trade networks, and a series of choices that shaped the world we live in today.

Life wasn't just a slow retreat.

Honestly, the real story is much messier. It's about the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) playing global superpowers against each other like a high-stakes chess match. It's about the "middle ground" in the Great Lakes region where cultures blurred so much that European traders often lived, dressed, and spoke like their Indigenous neighbors. If you think the story of the 17th and 18th centuries is just "Europeans arrived and took over," you're missing the most interesting parts of the narrative.

The Myth of the Untouched Wilderness

Before the first permanent English chimneys started smoking at Jamestown or Plymouth, the Americas were already a managed landscape. This wasn't some "virgin wilderness." That’s a trope. From the managed forests of the Northeast—cleared of underbrush by controlled burns to encourage deer populations—to the massive agricultural complexes of the Mississippian cultures, the land was lived-in.

Then came the "Great Dying."

Historians like Alfred Crosby have spent decades documenting the "Columbian Exchange," and the numbers are staggering. Smallpox, measles, and influenza didn't just kill people; they shattered entire social structures. By the time many colonists actually started settling inland, they weren't finding "wild" land. They were finding the abandoned towns and overgrown cornfields of civilizations that had been decimated by germs traveling faster than the settlers themselves.

Power Dynamics and the Beaver Wars

By the mid-1600s, Native Americans in Colonial America were the primary power brokers in the interior of the continent. Take the Haudenosaunee Confederacy. They weren't just "participating" in the fur trade; they were trying to monopolize it.

The Beaver Wars were brutal.

💡 You might also like: When Was Slavery a Thing? The Brutal Truth About Why It Never Really Stopped

As the demand for pelts in Europe skyrocketed, the Iroquois launched a series of massive military campaigns to expand their hunting grounds and control the flow of goods to the Dutch and English. They basically wiped out or dispersed the Hurons, Eries, and Neutrals. It was a massive geopolitical shift.

Think about it this way: the survival of the early English and French colonies often depended entirely on which Indigenous nation decided to tolerate them that month. The colonies were tiny, fragile outposts clinging to the coast. Inside those outposts, people were often starving. Outside, Indigenous empires were debating whether the newcomers were more useful as trading partners or more dangerous as neighbors.

The "Middle Ground" and Cultural Blurring

There's this concept popularized by historian Richard White called "The Middle Ground." It basically describes the Great Lakes region (the pays d'en haut) where neither the French nor the Algonquin-speaking peoples could achieve total dominance.

What happened? They compromised.

French fur traders (the coureurs des bois) didn't just show up and demand things. They had to follow Indigenous protocols. This meant participating in gift-giving ceremonies, marrying into powerful families, and learning the language. You had a world where European men were wearing moccasins and Indigenous leaders were using brass kettles and flintlock rifles. It was a hybrid society.

It wasn't just about guns and bibles. It was about everyday stuff.

- Indigenous women played a massive role as "cultural brokers." By marrying European traders, they ensured their kin had access to trade goods, while the traders gained a safety net and expert local knowledge.

- Glass beads, which we often dismiss as "trinkets," were actually deeply symbolic. To many Eastern Woodlands groups, the color and clarity of the beads resonated with traditional beliefs about spiritual power and "white light."

King Philip’s War: The Turning Point

If there’s one event that changed the trajectory for Native Americans in Colonial America, it was King Philip’s War (1675-1678). It was named after Metacom (called King Philip by the English), a Wampanoag leader.

This was the bloodiest conflict in American history per capita.

💡 You might also like: Who is Lewis J. Liman? The Judge Handling America's Most Complex Legal Battles

Metacom saw the writing on the wall. The English were no longer just trading; they were encroaching on land, letting their cattle destroy Indigenous crops, and trying to impose their legal system on sovereign people. He formed a massive uprising. For a while, it looked like the English might actually be pushed back into the sea.

The war was devastating. Towns were burned to the ground. Thousands died. In the end, the English won, but only by enlisting the help of the Mohawks and Mohegans. The aftermath was grim. Surviving Wampanoag and Narragansett people were often sold into slavery in the Caribbean. This war effectively broke the power of Indigenous nations in southern New England and set a precedent for the "total war" tactics that would be used for the next two centuries.

Diplomacy, Treaties, and the "Covenant Chain"

Politics in the 1700s were incredibly complex. The British didn't just rule; they negotiated. The "Covenant Chain" was a series of alliances between the British colonies and the Iroquois Confederacy.

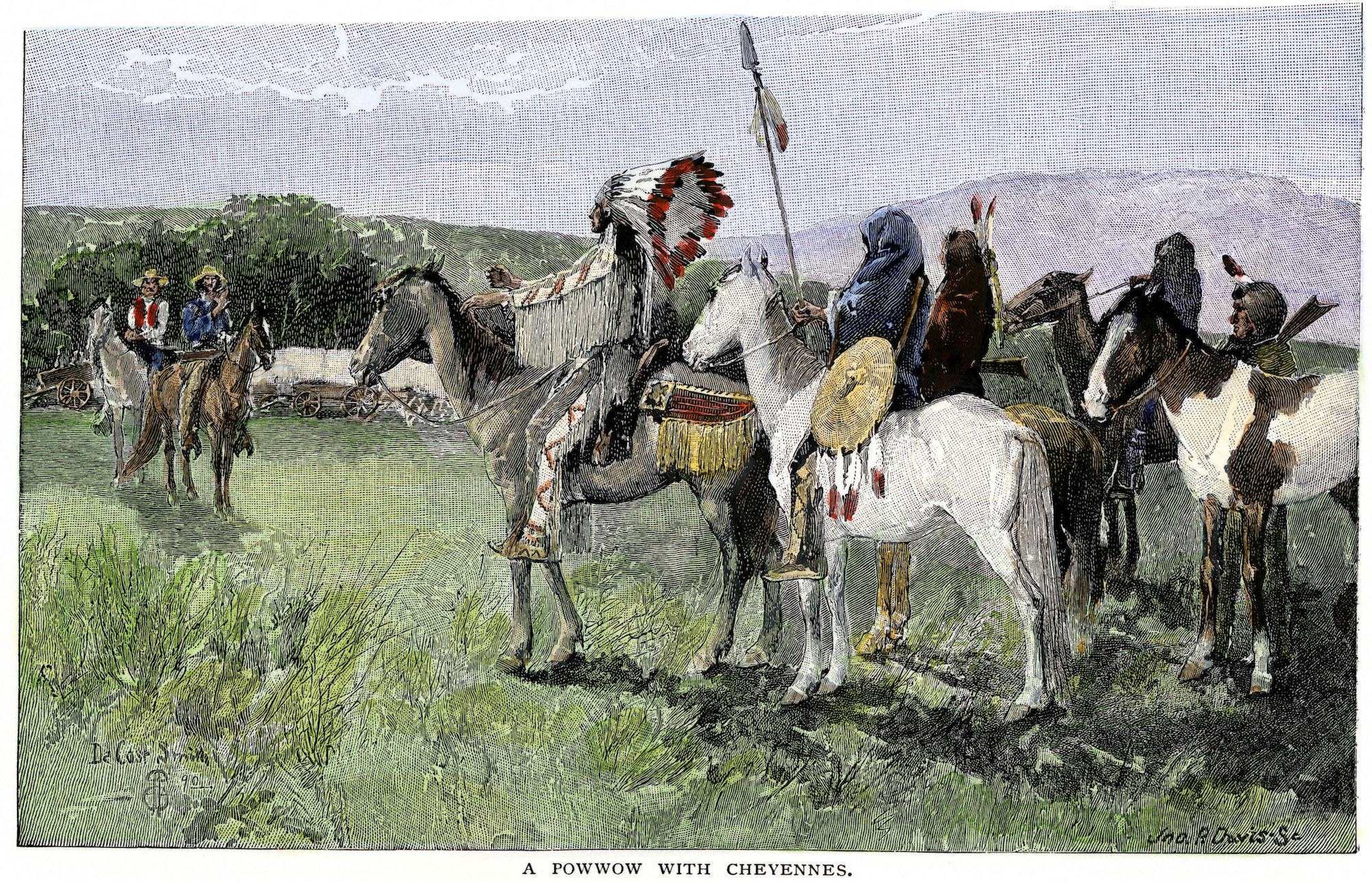

Meetings were formal affairs.

Leaders used wampum belts—intricate shells woven into patterns—to record agreements and "speak" their intentions. If you didn't bring enough gifts to a treaty council, you weren't just being cheap; you were being insulting and untrustworthy. The British government eventually realized that the individual colonies were terrible at managing these relationships, leading to the creation of the Proclamation of 1763. This line, drawn down the Appalachian Mountains, was supposed to stop settlers from moving west into Indigenous lands.

It didn't work.

The settlers ignored it. This tension—between a central government trying to maintain alliances with Native nations and settlers wanting to take land—was one of the primary "hidden" causes of the American Revolution.

Realities vs. Common Misconceptions

People often ask: "Why didn't they just unite and kick the Europeans out?"

It’s a fair question, but it ignores how these nations saw themselves. Asking why the Cherokees and the Shawnees didn't just "team up" against the English is like asking why the French and Germans didn't "team up" against an outside threat in the 1700s. They were different nations with their own histories, rivalries, and languages.

Also, the "noble savage" versus "bloodthirsty warrior" tropes are both equally useless. Indigenous people were pragmatic. They were farmers, traders, diplomats, and parents. They adopted European technology—like wool blankets and metal needles—because it made life easier, not because they were "losing" their culture. Using a gun doesn't make you any less Indigenous than using a smartphone makes you "less traditional" today.

🔗 Read more: North Carolina Winter Storm Warning: Why Your Prep Usually Fails and What Actually Works

Economic Interdependence

For a long time, the colonies were an "Indigenous world" with European fringes. The economy relied on it. The deerskin trade in the Southeast (Georgia and the Carolinas) saw millions of skins shipped to Europe. In exchange, the Creeks, Cherokees, and Chickasaws received textiles, tools, and weapons.

This created a cycle of dependency.

Once you start hunting with a rifle, you need gunpowder and lead. You can't make those yourself. This gave the colonial governments a massive lever of power. If a group became "troublesome," the governors would simply cut off the trade of ammunition. It was an early form of economic sanctions.

Practical Insights and How to Learn More

Understanding the role of Native Americans in Colonial America requires looking past the "frontier" myths. If you're looking to dive deeper into the actual history—the kind that moves beyond the Thanksgiving story—here are some concrete ways to do it.

Follow the Primary Sources

Don't just read summaries. Look for the "Jesuit Relations" (reports from French missionaries) or the recorded minutes of treaty councils in Pennsylvania and New York. These documents show the actual dialogue and the sophisticated arguments made by Indigenous orators like Canasatego or Hendrick Tejonihokarawa.

Visit Indigenous-Led Museums

The Mashantucket Pequot Museum in Connecticut or the Museum of the Cherokee Indian in North Carolina offer perspectives you won't get from a standard state-run historical site. They focus on continuity—showing that these cultures didn't disappear in 1776; they evolved.

Re-examine Your Local History

Most people live on land that was once part of a specific Indigenous nation’s territory. Use tools like Native-Land.ca to identify whose land you are on. Then, look up the specific treaties that transferred that land. You’ll often find a much more complex (and often heart-wrenching) story than "the settlers moved in."

Read Modern Indigenous Scholars

For a truly nuanced view, look into the work of historians like Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, Ned Blackhawk, or Margaret Bruchac. They are reframing the colonial period as a time of Indigenous persistence rather than just a tragic ending.

History isn't a static thing. It's an ongoing investigation. By looking at the colonial era as a shared (and contested) space, we get a much clearer picture of how the United States actually came to be. It wasn't just a British project; it was a messy, violent, and fascinating collaboration between multiple worlds.

Next Steps for Deepening Your Knowledge

- Locate your watershed: Research the Indigenous history of the specific river valley or coastal area where you live. Colonial history was almost always dictated by water access.

- Analyze a Treaty: Find the text of a major treaty, such as the Treaty of Lancaster (1744). Note the specific grievances listed by the Indigenous speakers; they often highlight issues like livestock trespass and trade fraud that are omitted from general history.

- Support Tribal Historic Preservation Offices (THPO): Many tribes have offices dedicated to preserving their archaeological and cultural sites. Following their newsletters provides updates on how colonial-era sites are being managed and interpreted today.