Walk into any gift shop in the Southwest and you’ll see them. Little silver kokopellis. Dreamcatchers made with plastic beads. T-shirts with stylized wolves. Most of the time, we treat Native American symbols like interior design choices or cool tattoos, but that's a massive misunderstanding of what these images actually do. They aren't just "art." For Indigenous communities from the Haida in the Pacific Northwest to the Seminole in Florida, these symbols are more like legal documents, prayers, and historical records wrapped into one.

Context is everything. You can't just pluck a symbol out of a culture and expect it to mean the same thing on a coffee mug. Honestly, it's kind of like trying to read a single word out of a massive novel and claiming you know the whole plot.

The Thunderbird Isn't Just a Cool Bird

Take the Thunderbird. You’ve probably seen it on everything from patches to car logos. In many Algonquian and Iroquoian traditions, the Thunderbird is a supernatural entity of immense power. It's not just a "symbol of strength." It is a protector. Some stories describe the flapping of its wings as the sound of thunder itself, while lightning flashes from its eyes.

But here is the thing: the meaning shifts depending on who you ask. For the Lakota, the Wakį́yan are the "Winged Ones," beings that live at the four corners of the earth. They aren't "birds" in the way we think of a pigeon or a hawk. They represent the cleansing power of the storm. When you see this symbol on a piece of authentic jewelry or a totem pole, it’s often tied to the idea of a warrior’s protection or a spiritual connection to the sky. It isn't a static icon. It’s a living part of a belief system that views the weather as a dialogue between the earth and the heavens.

Misunderstanding the Kokopelli

If there is one image that has been absolutely sterilized by modern tourism, it’s the Kokopelli. You know the one—the hunched-back flute player. People put him on garden stakes and kitchen tiles. Most folks think he’s just a "god of music" or a "happy traveler."

That is barely scratching the surface. In Hopi culture, Kokopelli is a fertility deity. He’s a bit of a trickster. Historically, his "hump" wasn't just a curved spine; in many ancient petroglyphs, it was a sack of seeds he carried to ensure a good harvest. Or, in some more explicit versions that you won’t find at the airport gift shop, the hump represented a more literal symbol of virility. He’s complicated. He represents the messy, beautiful, reproductive power of nature. When you strip away the complexity to make him a "cute" flute player, you lose the agricultural and social weight he carries for the Puebloan people.

The Medicine Wheel as a Map

Then there’s the Medicine Wheel. You’ve likely seen the circle divided into four colored sections—usually black, white, red, and yellow.

It’s easy to call it a "symbol of harmony." But it's actually a sophisticated philosophical tool. Dr. Chuck Ross and other scholars have noted how the wheel functions as a framework for understanding the four directions, the four stages of life (infancy, youth, adulthood, elderhood), and even the four seasons. It’s a compass for living. It’s not just a pretty circle. It represents the "Sacred Hoop" of the nation. If one section is out of alignment, the whole thing fails. It’s about balance, sure, but it’s also about the harsh reality that life requires constant recalibration to stay healthy.

Why "Native American Symbols" Aren't Universal

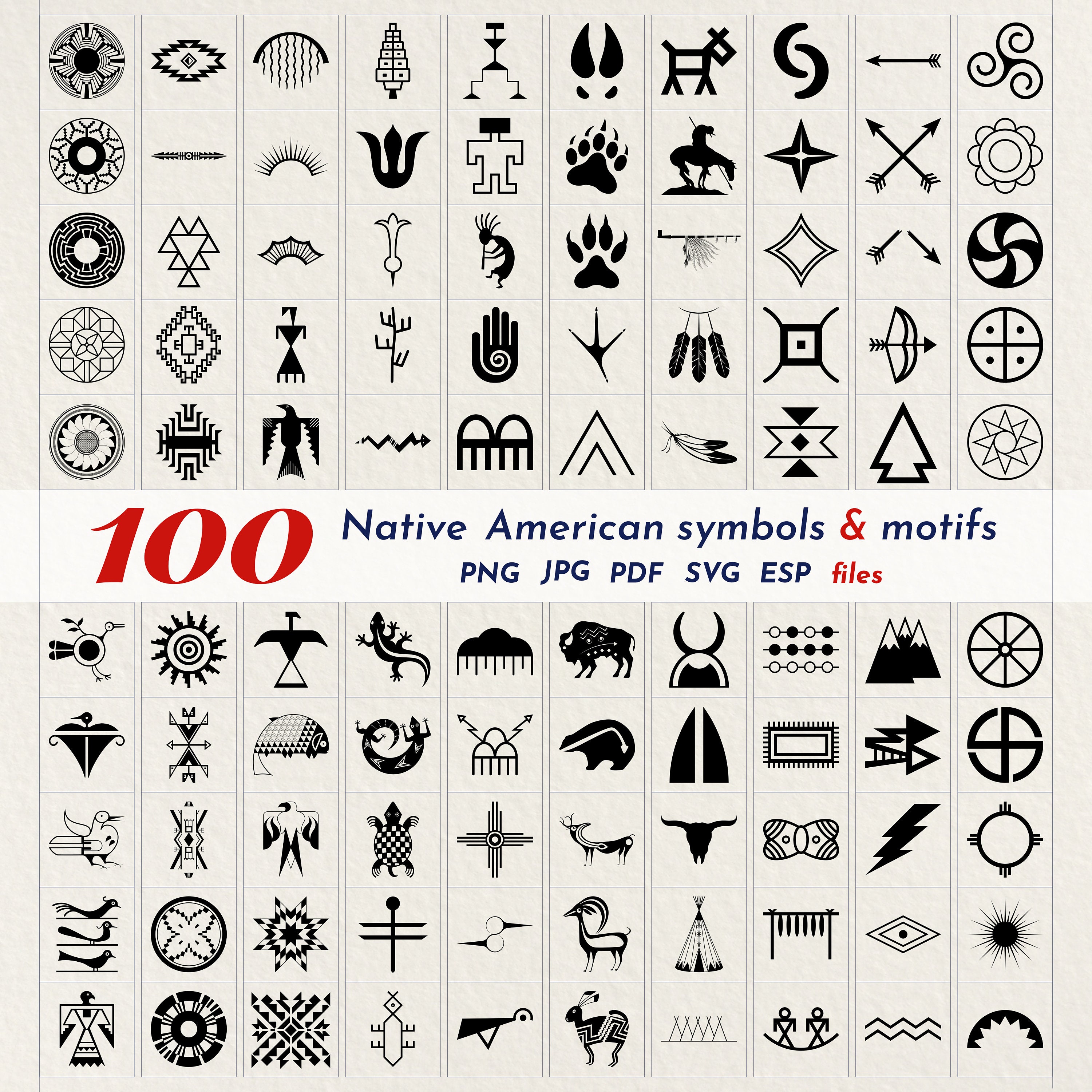

One of the biggest mistakes people make is grouping every tribe together. There is no single "Native American" culture. There are hundreds of federally recognized tribes, each with its own distinct language and visual vocabulary.

A symbol used by the Navajo (Diné) in the high desert of Arizona might mean absolutely nothing to a Mi’kmaq person in Nova Scotia. For instance, the "Whale" is a massive, central figure in Northwest Coast art (Tlingit, Haida, Coast Salish). It represents family and long-term memory. But if you go to the Great Plains, the Whale isn't part of the symbolic lexicon because, well, there aren't many whales in Nebraska. Instead, you see the Buffalo.

The Buffalo is the "provider." It’s the symbol of self-sacrifice because the animal gave everything—meat, hide, bone—to keep the people alive. Using a Buffalo symbol if you are from a coastal tribe would be culturally confusing. It’s important to realize that Native American symbols are intensely regional. They are tied to the dirt, the water, and the animals of a specific plot of land.

The Problem with "Native-Inspired" Art

We need to talk about the Indian Arts and Crafts Act of 1990. It’s a federal law in the United States that basically says it’s illegal to offer or display for sale any art or craft product in a manner that falsely suggests it is Indian produced or an Indian product.

Why does this matter for symbols? Because symbols are intellectual property.

When a massive fashion brand puts an "Aztec" print (which is usually a mix of several different tribal patterns) on a pair of leggings, they are stripping the meaning out of the image. For many Indigenous people, seeing their sacred symbols used as "boho chic" patterns is painful. It’s not about being "offended" in a superficial way. It’s about the fact that these symbols were often banned. During the era of residential schools and the suppression of Indigenous religions, people were literally punished for using these symbols. To see them now used as a cheap aesthetic choice by the same culture that tried to erase them is a massive irony that most people miss.

Water and the Serpent

The Horned Serpent is another one that gets misinterpreted. In the Mississippian culture and among the Muscogee (Creek) and Cherokee, the Horned Serpent (or Uktena) is a powerful dweller of the "Under World."

In Western culture, serpents or dragons are often "evil." We want to kill the dragon. But in Indigenous symbolism, the Horned Serpent isn't "bad." It’s dangerous, yes, but it’s also a source of great power and wisdom. It controls the water. If you respect it, it provides. If you don't, it destroys. This nuance—the idea that a "monster" can be a source of life—is a hallmark of Indigenous thought that rejects the simple good-versus-evil binary found in a lot of European folklore.

💡 You might also like: Por la plata baila el mono: Why this cynical saying is actually the truth about human nature

Symbols of Resistance

Not all symbols are ancient. Some of the most potent Native American symbols are actually quite modern.

The "Inverted Flag" or the "Raised Fist" combined with traditional patterns became huge during the American Indian Movement (AIM) in the 1970s. These are symbols of survival. They represent a people who were supposed to disappear according to 19th-century "Manifest Destiny" logic, but didn't. When you see a modern Indigenous artist like Bunky Echo-Hawk or Wendy Red Star use traditional symbols in a pop-art context, they are reclaiming the narrative. They are saying, "Our symbols are not relics of a dead past. They are tools for a living future."

How to Respect These Symbols Today

If you actually care about the history and the people behind these images, you have to do the work. You can't just Google "cool native symbols" and call it a day.

- Research the specific tribe. If you see a symbol you like, find out where it comes from. Is it Anishinaabe? Is it Zuni? Knowing the origin is the first step toward respect.

- Buy from the source. If you want a piece of art with Indigenous symbolism, buy it from an Indigenous artist. This ensures the meaning is preserved and the money goes back into the community that created the culture.

- Check the materials. Authentic symbols are often tied to specific materials—turquoise, red pipestone, cedar, or dentalium shells. The material is often just as symbolic as the shape.

- Understand "Open" vs. "Closed" symbols. Some symbols are "open," meaning they are meant to be shared with the world as a form of education. Others are "closed," reserved only for specific ceremonies or initiated members of a tribe. If you aren't sure, don't use it.

The Actionable Truth

The reality is that Native American symbols are a language. If you don't speak the language, you shouldn't be trying to write poetry with it.

Start by looking at the "Social Responsibility" pages of Indigenous-led organizations like the Native American Rights Fund (NARF) or the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian. These institutions provide deep dives into how symbols are used in legal battles over land and water rights today.

Stop looking at these symbols as "art" and start looking at them as "identity." When you see a "Water is Life" (Mni Wiconi) symbol, realize that it isn't just a catchy slogan from the Standing Rock protests. It is a literal statement of fact rooted in centuries of Lakota philosophy. The next time you encounter an Indigenous symbol, ask yourself: do I know the story, or am I just looking at the picture? The answer to that question is the difference between appreciation and appropriation.

📖 Related: Why 2724 Pacific Avenue San Francisco Is the Billionaire Row Home Everyone is Watching

Support Indigenous creators directly through platforms like the Santa Fe Indian Market or the Heard Museum Shop. Read books by Indigenous authors like Robin Wall Kimmerer or David Treuer to get the "why" behind the "what." This is how you move from being a consumer of a culture to a person who actually understands it.