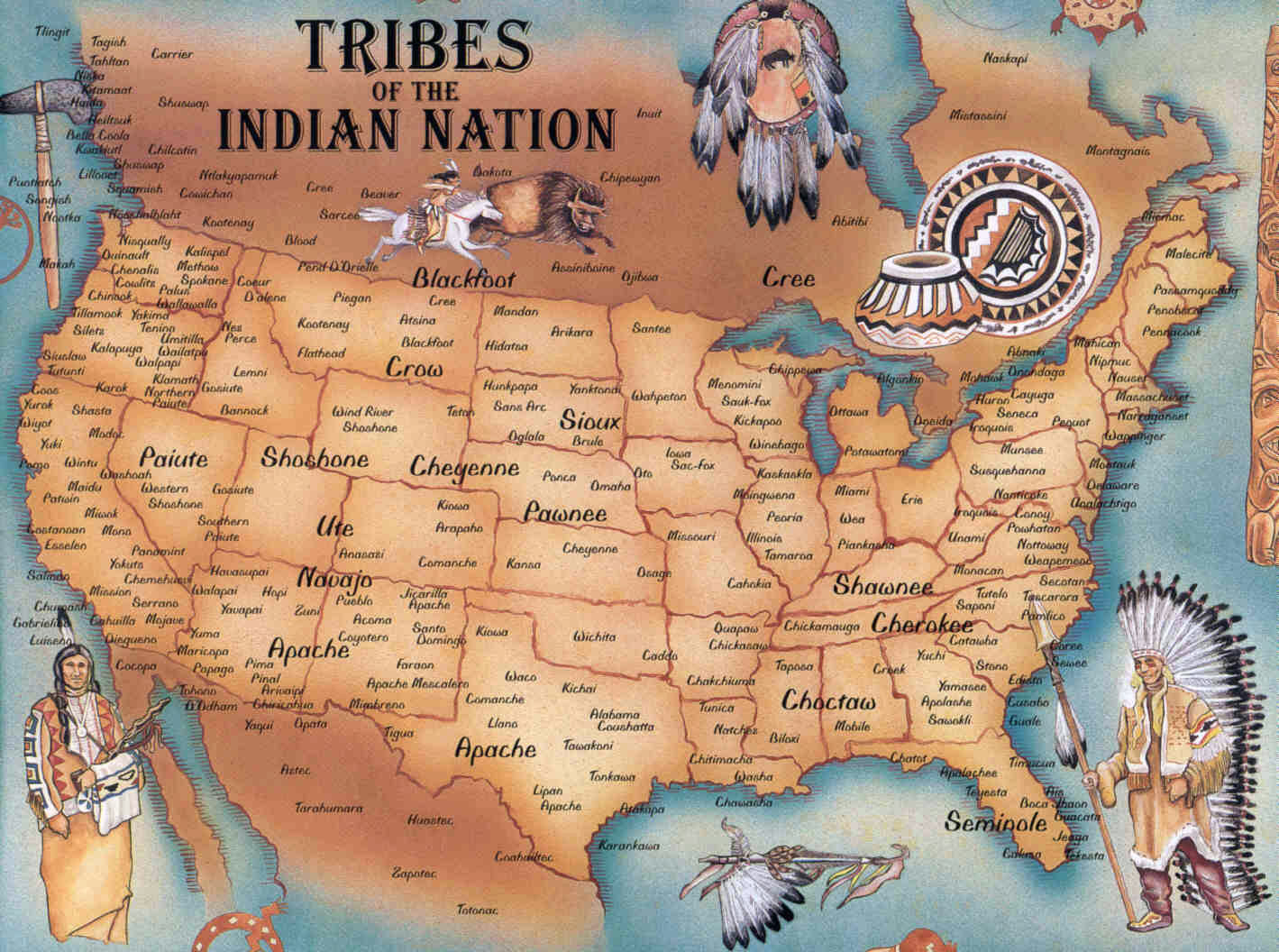

Maps aren't just lines on paper. Most of us grew up staring at those classroom posters showing fifty neat states or the clean-cut borders of Canada and Mexico. It feels permanent. Solid. But if you look at a Native American map of North America, that entire rigid structure basically evaporates. You aren't looking at "new" land or a "discovered" wilderness. You're looking at an incredibly dense, overlapping, and ancient network of sovereign nations that existed long before a single European ship hit the horizon.

Think about it.

When we talk about North America today, we use names like "New York" or "British Columbia." But those names are placeholders. Underneath them is a deep history of movement, trade, and stewardship that spans thousands of years. Maps created by or about Indigenous peoples don't just show where someone lived; they show who they are in relation to the earth.

✨ Don't miss: Finding Dr Seuss Books for Free Without Dealing With Sketchy PDFs

The Problem With Modern Borders

The maps we use today are mostly about ownership. They’re about who pays taxes where and where one government's laws stop and another's begin. A Native American map of North America operates on a totally different logic. Indigenous geography is often defined by watersheds, migration patterns of animals, and sacred landmarks.

Traditional western cartography is "top-down." It assumes a bird's-eye view. Indigenous mapping, historically, was often "inside-out." It was based on lived experience. An elder might describe a territory not by miles, but by how many suns it took to walk from the "place where the water boils" to the "jagged red rocks."

It’s messy. Honestly, it’s supposed to be.

Groups like the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois Confederacy) didn't just have a border; they had a sphere of influence and complex treaties with neighbors like the Anishinaabe. These weren't hard fences. They were relationships. When you look at projects like Native-Land.ca, which is arguably the most famous modern attempt to visualize these territories, you see colors bleeding into each other. That isn't a mistake. It's a reflection of reality. Shared hunting grounds and overlapping seasonal camps were the norm, not the exception.

Not Just One Map, But Thousands

There is no single "Native American map." That’s a huge misconception. We’re talking about over 570 federally recognized tribes in the U.S. alone, plus hundreds more in Canada and Mexico. Each had—and has—its own way of defining space.

Take the Diné (Navajo), for example. Their traditional territory is defined by four sacred mountains: Blanca Peak in the east, Mount Taylor in the south, the San Francisco Peaks in the west, and Mount Hesperus in the north. If you aren't within the sightline of those peaks, you're technically outside the traditional "map" of the Diné. It’s a geography of the spirit as much as the soil.

Contrast that with the maritime maps of the Haida or Tlingit in the Pacific Northwest. Their "roads" were the ocean currents. Their "landmarks" were hidden reefs and salmon runs. Mapping that on a flat piece of paper is almost impossible because it changes with the tide.

Then you have the great plains. Nations like the Lakota or Comanche moved with the buffalo. Their map was fluid. It shifted. It breathed. Trying to pin a 17th-century Comanche map down to a specific GPS coordinate is like trying to catch smoke with a net. They controlled a massive territory known as Comancheria, but its "borders" were defined by who was strong enough to hold the trade routes at any given moment.

Mapping as a Tool of Resistance

For a long time, mapping was used against Indigenous people.

Colonial powers used maps to "empty" the land. They’d draw a square, call it "Unorganized Territory," and suddenly, in the eyes of European law, the people living there didn't exist. This is what scholars call terra nullius—nobody's land.

But today, the Native American map of North America is being used as a tool for "counter-mapping." Indigenous cartographers are reclaiming their names.

Have you ever looked at a map of Alaska and seen "Denali" instead of "Mount McKinley"? That’s a victory of mapping. It’s about putting the original language back on the dirt. When a tribe maps their ancestral burial grounds or traditional berry-picking spots, they aren't just making a graphic; they are asserting legal rights to the land. In many court cases involving treaty rights or pipelines, these Indigenous maps are the primary evidence used to prove that a tribe has "continual use" of the area since time immemorial.

The Tech Behind the Re-Mapping

It's not all deer-hide sketches and oral histories anymore. Indigenous communities are using some of the most advanced tech on the planet.

- GIS (Geographic Information Systems): Tribes use this to track water quality, manage timber, and protect sacred sites from developers.

- Lidar: This laser-scanning tech helps find ancient structures or trails hidden under thick forest canopies that don't show up on Google Earth.

- Story Maps: These are digital platforms where clicking a location triggers an audio clip of an elder telling a story in their native tongue about that specific hill or river.

Margaret Pearce, a cartographer and member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, is a huge name here. She created a map called "Coming Home to Indigenous Place Names in Canada." It doesn't show provinces. It doesn't show highways. It shows thousands of Indigenous place names, reminding everyone that the land was already named before the "explorers" arrived.

Why This Matters to You Right Now

You might think, "Okay, cool history lesson, but why does a Native American map of North America matter to me?"

📖 Related: Writing a Love Letter to Your Girlfriend: Why the Old-School Approach Still Wins in 2026

Because it changes how you move through the world.

When you realize you're standing on Caddo land or Ohlone land, the "scenery" becomes a "neighborhood." It builds a sense of accountability. If you're a hiker, a traveler, or even just someone buying a house, knowing the Indigenous history of that plot of land adds a layer of depth that a standard zip code can't touch.

It also highlights the environmental stakes. Indigenous-managed lands often have higher biodiversity than "protected" parks. Why? Because the maps weren't designed to keep people out; they were designed to keep people involved in the ecosystem. Mapping these traditional practices helps us understand how to survive climate change by looking at how people lived on this continent for 10,000 years without destroying it.

How to Engage with Indigenous Geography

If you want to actually see this for yourself, don't just search for a static image on Google Images. Use interactive tools.

Go to Native-Land.ca. Type in your address. Look at the names that pop up. See if you can find the website for those specific tribes. Most nations have an "official" map on their government site that shows their current reservation boundaries versus their ancestral territory. The difference between those two shapes is often staggering and tells a story of forced removal and resilience better than any textbook.

💡 You might also like: Can dogs eat whey protein? What you need to know before sharing your shake

Check out the Indigenous Mapping Collective. They are a group of tech-savvy folks helping tribes use drones and data to map their own futures. It’s about data sovereignty—making sure the tribes own the maps of their own land, rather than some government agency.

Actionable Steps for the Curious

Don't just be a passive observer. Here is how you can actually use this knowledge:

- Acknowledge the Land: If you're hosting an event or even just writing a blog post, find out whose ancestral territory you're on. Don't just do a "land acknowledgment" because it's trendy; do it because you actually looked at the map and learned something.

- Support Indigenous Tourism: When traveling, look for tours or cultural centers run by the local tribes. They’ll show you a "map" of the area you’d never find in a guidebook.

- Use Native Names: When referring to landmarks, try to use the original names alongside the colonial ones. It’s a small way to help keep the "original map" alive in the public consciousness.

- Consult Primary Sources: If you're researching a specific area, look for maps produced by the Tribal Historic Preservation Office (THPO) of that region. They are the experts.

The map of North America isn't finished. It’s still being drawn. Every time an Indigenous name is restored or a treaty boundary is recognized, the map gets a little more honest. It’s less about a "discovery" and more about a long-overdue "recognition."