You’ve probably seen the pictures of Plymouth Rock. It’s small. It’s sitting in a pit. It’s a bit of a letdown if we’re being honest. But just a mile or so up the road, hidden in a residential neighborhood on Allerton Street, sits something that looks like it belongs in a European capital rather than a quiet Massachusetts suburb. The National Monument to the Forefathers is absolute massive. We're talking 81 feet of solid Maine granite. It’s actually one of the tallest solid granite statues in the entire world, yet most people driving to Cape Cod blow right past the exit without even knowing it exists.

It’s weirdly quiet there. You can stand at the base of this thing and look up at the central figure, Faith, who points one finger toward heaven and holds a Bible in her other hand, and realize she’s over 21 feet tall just by herself. This isn't just a "thank you" note to the Pilgrims carved in stone. It’s a literal blueprint of what the founders thought made a society actually work. If you look closely at the smaller figures sitting at the base—Morality, Law, Education, and Liberty—you start to see a very specific philosophy that has nothing to do with modern political bickering and everything to do with 19th-century intellectual grit.

What Most People Get Wrong About the Monument's History

A lot of folks assume this was built right after the Mayflower landed. Not even close. The Pilgrim Society started chatting about this back in the 1820s, but the cornerstone wasn't even laid until 1859. Think about that timing. The United States was literally tearing itself apart. The Civil War was bubbling over. While the country was fracturing, Hammatt Billings, the architect, was trying to design something that anchored the American identity to a specific set of virtues.

It took forever to finish. Thirty years, to be exact.

Money was a constant nightmare. Because it was funded by small donations rather than a massive federal check, the construction dragged on through the war, through economic shifts, and through the death of Billings himself. His brother, Joseph, had to take over the project. When it was finally dedicated in August 1889, the world had changed. We weren't a collection of colonies anymore; we were an emerging global power. The monument serves as a time capsule of how the Victorian era viewed the 1600s. It’s a layer cake of history.

The Secret Language of Granite

If you walk around the base, you'll see four seated figures. They aren't just there for decoration. Each one represents a "pillar" that the designers believed supported the main figure of Faith.

💡 You might also like: Where to Stay in Seoul: What Most People Get Wrong

Take Morality. She’s looking inward. She’s got the Ten Commandments in one hand and the scroll of Revelation in the other. But look at the smaller carvings under her throne: it’s the Prophet and the Evangelists. The idea was that a society can't function if the individuals don't have an internal compass.

Then there’s Law. He’s sitting there looking stern, holding a book. Underneath him, you see carvings representing Justice and Mercy. It’s a reminder that the Pilgrims weren't just religious refugees; they were legal innovators. They wrote the Mayflower Compact because they knew that without a shared agreement on rules, they’d all be dead by February.

Education is perhaps the most interesting one because of how much the Pilgrims valued literacy. They wanted kids to read so they could read the Bible for themselves, not just take a preacher's word for it. The figure holds a "Book of Knowledge" and is flanked by representations of Youth and Wisdom.

Finally, there’s Liberty. He’s a warrior. He’s got a sword, a helmet, and a fallen chain. He represents "Liberty Victorious." He’s sitting on the skins of a lion, which is a pretty unsubtle nod to breaking away from the British Crown. It’s the result of the other three pillars working together. Basically, you don't get Liberty if you don't have Education, Law, and Morality first.

Why Nobody Talks About the Architect Hammatt Billings

Hammatt Billings was a bit of a genius who got lost in the shuffle of history. He was a prolific illustrator—he actually did the original illustrations for Uncle Tom’s Cabin. He was obsessed with the idea of "moral architecture." He didn't just want to build a pretty statue; he wanted to build a sermon.

📖 Related: Red Bank Battlefield Park: Why This Small Jersey Bluff Actually Changed the Revolution

Originally, he wanted the National Monument to the Forefathers to be twice as big. He envisioned something nearly 150 feet tall, which would have rivaled the Statue of Liberty (which, ironically, was being built around the same time in France). But the budget just wasn't there. So they scaled it down. Even at "half size," the scale is disorienting. When you stand next to the buttresses, you feel like an ant. The granite has this rough, gray texture that feels incredibly permanent. It’s Maine granite, pulled from the earth and hauled down to Plymouth to stand against the salt air forever.

The Controversy You Won't See on the Plaque

We have to be honest: the monument tells a very specific, one-sided story. It’s the "Pilgrim-as-Hero" narrative. In the late 1800s, that was the only narrative being told in mainstream white America. You won't find much mention here of the Wampanoag people or the devastating reality of what colonization meant for the indigenous populations.

The carvings on the panels—showing the Departure from Delft Haven, the Signing of the Mayflower Compact, the Landing at Plymouth, and the First Treaty—portray a very orderly, almost divine progression of events. Modern historians look at these panels and see a masterpiece of 19th-century propaganda. That doesn't mean the monument isn't worth seeing. It means it’s a tool for understanding how Americans in the 1880s wanted to see themselves. They wanted to see themselves as the logical conclusion of a grand, moral journey. It’s as much a monument to 19th-century ideals as it is to 17th-century history.

How to Actually Visit (and What to Look For)

Don't just drive up, take a selfie, and leave. To really "get" the National Monument to the Forefathers, you need to do a few things.

First, check out the panels at the base. The detail is insane. The "Signing of the Mayflower Compact" panel is particularly dense. You can see the exhaustion in the faces of the men. You can see the quill and the ink. It’s a high-relief carving, meaning the figures almost pop out of the stone.

👉 See also: Why the Map of Colorado USA Is Way More Complicated Than a Simple Rectangle

Second, look at the orientation. The monument is positioned so that Faith is looking out toward the harbor, toward the direction the Mayflower came from. It’s a welcoming gesture and a defiant one at the same time.

Third, go at "golden hour." When the sun starts to dip, the granite catches the light in a way that makes the figures look almost alive. Because the park is rarely crowded, you can usually have the whole place to yourself. It’s a stark contrast to the zoo-like atmosphere around the Mayflower II replica downtown.

Actionable Tips for Your Trip

- Parking is free. There’s a small lot right at the site on Allerton Street. You don't need a permit or a ticket.

- Bring binoculars. Seriously. The detail on the face of "Faith" and the "Liberty" figure is way up there. You can't see the nuances of the expressions from the ground without some help.

- Read the names. There are names of the Mayflower passengers inscribed. It’s a weirdly personal touch on such a massive scale.

- Skip the weekend mid-day rush. Even though it's "hidden," it can get a few tour buses. Go early in the morning.

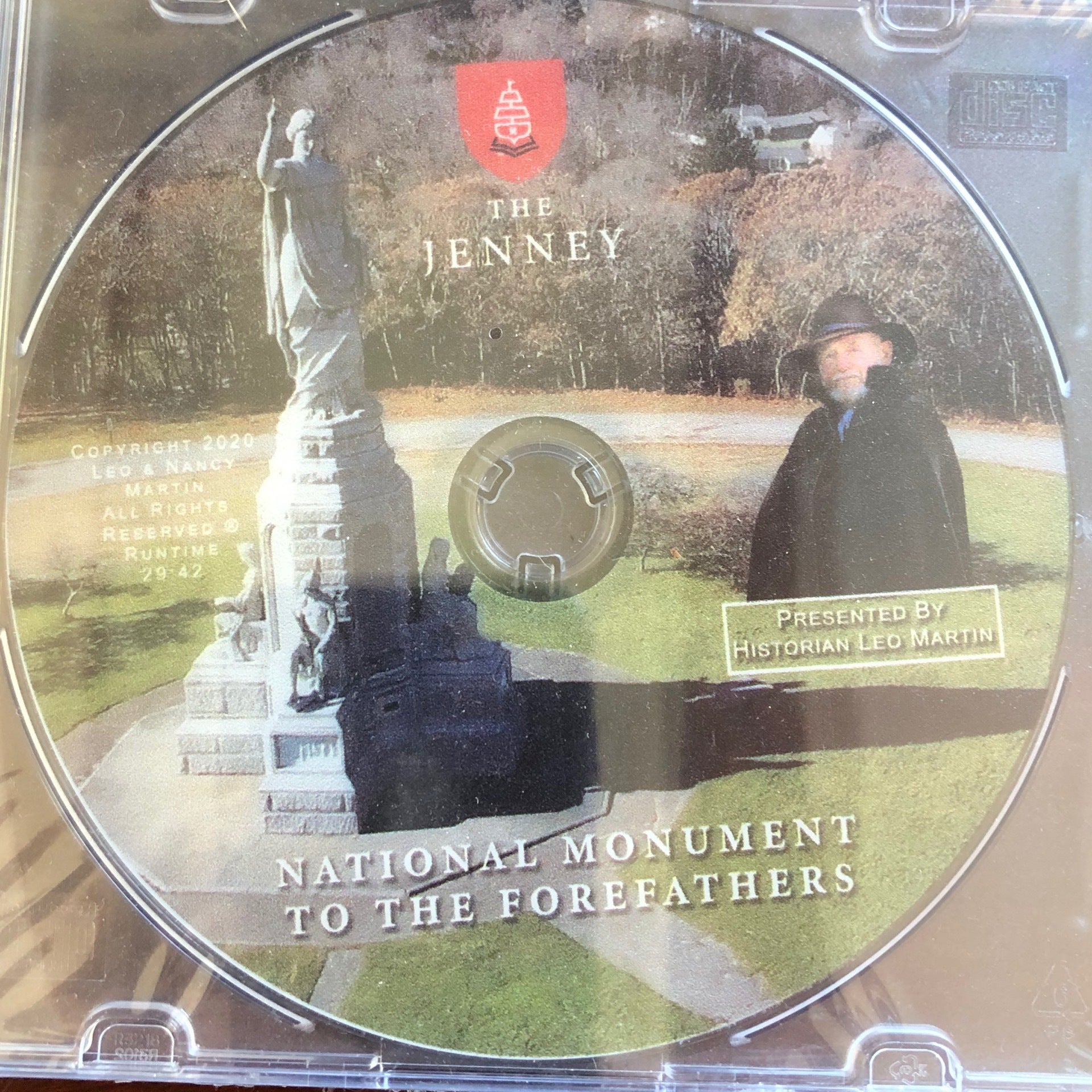

- Combine it with the Jenney Interpretive Centre. If you want the actual history of the Pilgrims to go with the symbolism of the statue, the folks at the Jenney (located nearby) do a great job of explaining the "why" behind the "what."

The National Monument to the Forefathers isn't just a hunk of rock. It’s a massive, heavy, gray argument for what a country should be. Whether you agree with the 1889 version of American history or not, standing in its shadow makes you realize just how much effort people put into defining their identity. It’s big, it’s loud, and it’s waiting for you to notice it.

Next Steps for Your Visit:

Map out a walking route from Plymouth Rock up to the monument. It’s about a 20-minute uphill walk through some pretty historic neighborhoods. Wear comfortable shoes because the grass around the monument is uneven. If you're a photography buff, bring a wide-angle lens; you’ll need it to fit the whole 81-foot structure into a single frame without backing up into someone's driveway. Check the local Plymouth weather—the hill catches the wind from the bay, so it's always about five degrees colder at the monument than it is at the waterfront.