Money is weird. Especially when you're talking about trillions of dollars that a government owes. If you’ve ever looked at a national debt over time graph, you probably felt a bit of vertigo. The line doesn't just go up; it practically teleports toward the ceiling. It looks like a ski jump in reverse.

But honestly, most of the screaming headlines you see about these charts miss the point. They focus on the "big scary number." Right now, the U.S. national debt is barreling past $34 trillion. That’s a lot of zeros. However, a raw number on a page doesn't tell you if a country is actually broke or just... busy. You have to look at the context.

The Shape of the Curve

When you pull up a national debt over time graph spanning from the late 1700s to today, it stays remarkably flat for a long time. It’s almost a straight line along the bottom of the chart for over a century. There are little blips. The Revolutionary War cost money. The Civil War caused a noticeable spike. But the real "climb" didn't start until the 20th century.

World War II changed everything.

That’s the first massive "hump" you see in the data. To fund the global effort, the U.S. borrowed like never before. By 1946, the debt-to-GDP ratio hit about 106%. We owed more than the entire country produced in a year. Yet, if you look at the graph for the next thirty years, something counterintuitive happens. The total debt didn't necessarily plummet, but the line relative to the size of the economy dropped like a rock. By the mid-1970s, it was down to around 23%.

📖 Related: Dow, Nasdaq, S\&P 500: What Really Happened This Week

Why? Because the economy grew faster than the borrowing. It’s like having a $5,000 credit card limit when you make $20,000 a year versus having a $10,000 limit when you make $200,000. The second person has "more debt," but they’re way more stable.

The Modern Era Explosion

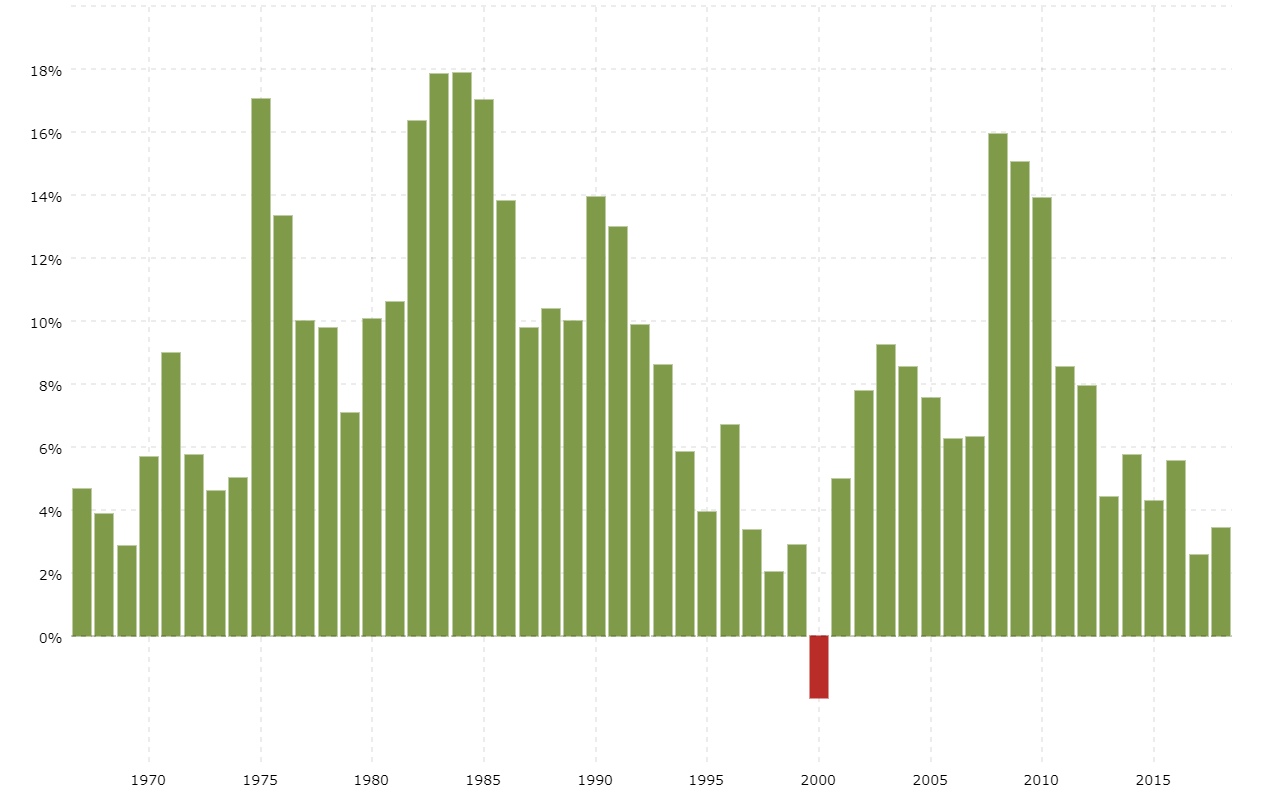

The 1980s started a new trend. Tax cuts combined with increased military spending under the Reagan administration saw the debt begin to outpace economic growth. Then came the 2008 financial crisis. The graph at that point looks like a rocket ship. The government flooded the system with cash to prevent a total collapse.

Then, COVID-19 happened.

If 2008 was a rocket, 2020 was a teleportation device. The trillions spent on stimulus checks, business loans, and healthcare infrastructure created a vertical line on the national debt over time graph that economists are still arguing about today. We are now back at debt-to-GDP levels that rival the peak of World War II.

Why the "Total Debt" Number is Kinda Misleading

If I told you a guy named Dave owes $1 million, you'd think Dave is in trouble. But if Dave is a billionaire, that million is pocket change. That’s why experts like Maya MacGuineas, president of the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, often talk about the sustainability of the debt rather than the total amount.

The U.S. has a unique advantage: the dollar is the world’s reserve currency.

People want to hold our debt. When you buy a Treasury bond, you are literally lending money to the government. Investors around the world—and even other countries like Japan and China—view these as the safest assets on the planet. This high demand keeps our interest rates lower than they would be for almost any other nation.

👉 See also: Rare Earth 2x ETF: Why This High-Stakes Bet Isn't For Everyone

But there is a ceiling. Or at least, a point where the interest starts to eat the rest of the budget.

The Interest Trap

This is the part of the graph people should actually worry about. It’s not just the debt; it’s the cost of the debt. For years, interest rates were near zero. Borrowing was basically free. You could rack up trillions and the monthly payment was manageable.

That changed in 2022 and 2023. When the Federal Reserve hiked rates to fight inflation, the cost of servicing that massive debt mountain spiked. We are now reaching a point where the U.S. spends more on interest payments than it does on the entire Department of Defense.

Think about that.

We pay more to "rent" the money we already spent than we do to maintain the world’s most powerful military. That’s the "hidden" line on a national debt over time graph that actually keeps Treasury officials up at night.

Comparing Us to the Rest of the World

It's easy to think the U.S. is uniquely bad at managing its checkbook. We aren't.

Look at Japan. Their debt-to-GDP ratio has hovered over 200% for years. By all traditional economic logic, their economy should have imploded decades ago. It hasn't. On the flip side, you have countries in the Eurozone that faced massive debt crises (think Greece) because they didn't have control over their own currency.

The U.S. is in a middle ground. We have the "exorbitant privilege" of printing our own money, but we also have a political system that treats the debt ceiling like a game of chicken.

📖 Related: 1000000 Won to Dollars: What Most People Get Wrong About the Exchange Right Now

Misconceptions That Just Won't Die

You've probably heard someone say, "China owns all our debt."

Actually, they don't. Not even close.

The biggest holder of U.S. debt is actually... the U.S. Social Security trust funds, the Federal Reserve, and American investors (like your 401k) own the vast majority of it. Foreign countries own about a quarter of the total. While China is a major player, they’ve actually been trimming their holdings lately. Japan currently holds more U.S. debt than China does.

Another big one: "We can just pay it off."

The global financial system is built on U.S. debt. If the U.S. suddenly had zero debt, the world economy would likely seize up. Treasury bonds are the "collateral" that makes international banking work. We don't need to get to zero. We just need the line on the national debt over time graph to stop rising faster than our ability to pay the interest.

What Happens Next?

There is no "magic number" where the economy explodes. Economics is more about psychology than physics. As long as people believe the U.S. will pay its bills, the system keeps humming. But if investors lose faith, they’ll demand higher interest rates. That creates a feedback loop. Higher rates lead to higher debt, which leads to less faith, which leads to even higher rates.

That’s the "death spiral" scenario.

How to Use This Information

If you are looking at these graphs to make investment decisions, pay attention to the "Debt Held by the Public" vs. "Total National Debt." The former is what actually affects the markets.

Actionable Steps for Navigating This Data:

- Watch the CBO Reports: The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) releases long-term budget outlooks twice a year. They are the gold standard for non-partisan debt data. Ignore the "pundit" charts on social media and go straight to the source.

- Monitor the Interest-to-Revenue Ratio: This is the most important metric. If the government is spending 15% or 20% of all tax revenue just on interest, that leaves less money for roads, schools, and tech. That’s where the "squeeze" happens.

- Diversify for Inflation: High debt often leads to governments "inflating their way out" by making the currency worth less. If the debt graph keeps going vertical, holding some assets that aren't tied to the dollar (like international stocks, real estate, or commodities) is a common hedge.

- Look at "Real" vs "Nominal": Always check if a national debt over time graph is adjusted for inflation. A dollar in 1950 isn't a dollar today. Raw charts that aren't inflation-adjusted are basically useless for real analysis.

The debt isn't a ticking time bomb that’s going to go off tomorrow. It's more like a slow-moving glacier. You can see it coming from miles away. The question is whether we move out of the way or just keep arguing about the size of the ice.